GUP TEAM

The Thames & Hudson Dictionary and Photography

Hardback / 440 pages / 307 x 202 mm

£65

“In the second decade of a century marked by the massive expansion of the internet and digital technology, it may seem almost perverse to publish a dictionary on paper,” writes editor Nathalie Herschdorfer in the opening line of the preface for the 440 page Thames & Hudson Dictionary of Photography. Well… at least they admit it.

In a new publication detailing the 180 years of photography’s existence thus far, Thames & Hudson walks us alphabetically through 1200 entries, from Abbas to Piet Zwart, of prominent photographers, agencies, inventors, scientists and more. Working from the idea that information on any given subject is by now far too vast and disorganized to distil any sense of relevance and importance, Herschdorfer worked with a team of 80 researchers and some 150 consultants in the field of photography to assemble the dictionary in order to provide that much-needed focus and structure. She emphasizes that the dictionary is not meant to replace digital resources, but rather, to serve as a complement: “The brief entries here will broaden the reader’s knowledge; the digital world is there if he or she wants to deepen it.”

There will of course be major names that our informed readers will immediately recognize: Hippolyte Bayard, Bernd and Hilla Becher, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Rinko Kawauchi, Jacques Henri Lartigue, Joel Meyerowitz, August Sander. Photographic techniques and processes are also included, such as calotype, cibachrome, collage, conservation and contact prints. There is much to be found among the breadth of information included in the dictionary, though arguably, as breadth is the primary focus of the publication, the problem is precisely in all the things it omits – what the dictionary presents here are notable highlights, and is by no means encyclopaedic in range.

Because the material is presented in dictionary form, the book does not lend itself to simply picking it up, sitting comfortably in a chair and reading, but rather, it’s more meant to serve as a reference for inspiration or as a starting point for research. Each entry is concise (roughly 50 – 300 words a piece) and focused on the facts. Any mentions of words or people that also appear in the dictionary are highlighted in the entry, for readers to know those listings can also be looked up. The appearance of this ‘linking’ strangely takes its styling from the web – each phrase looks enough like web linking to indeed make you second-guess the decision to print the publication, rather than publishing it in an e-book or online service, where readers could actually click between entries, or even search.

Stripped of narrative context and sorted according to alphabet – it is a dictionary, after all – the material perhaps loses some of the value that it might otherwise achieve from being collected by a panel of experts in the field. With only a cursory explanation, and no curatorial timeline or over-arching themes to give the reader clarity on movements and developments in the history of photography, the dictionary seems to be relying exclusively on its ability to provide accurate information and limited focus, in order to make its way to readers’ bookshelves.

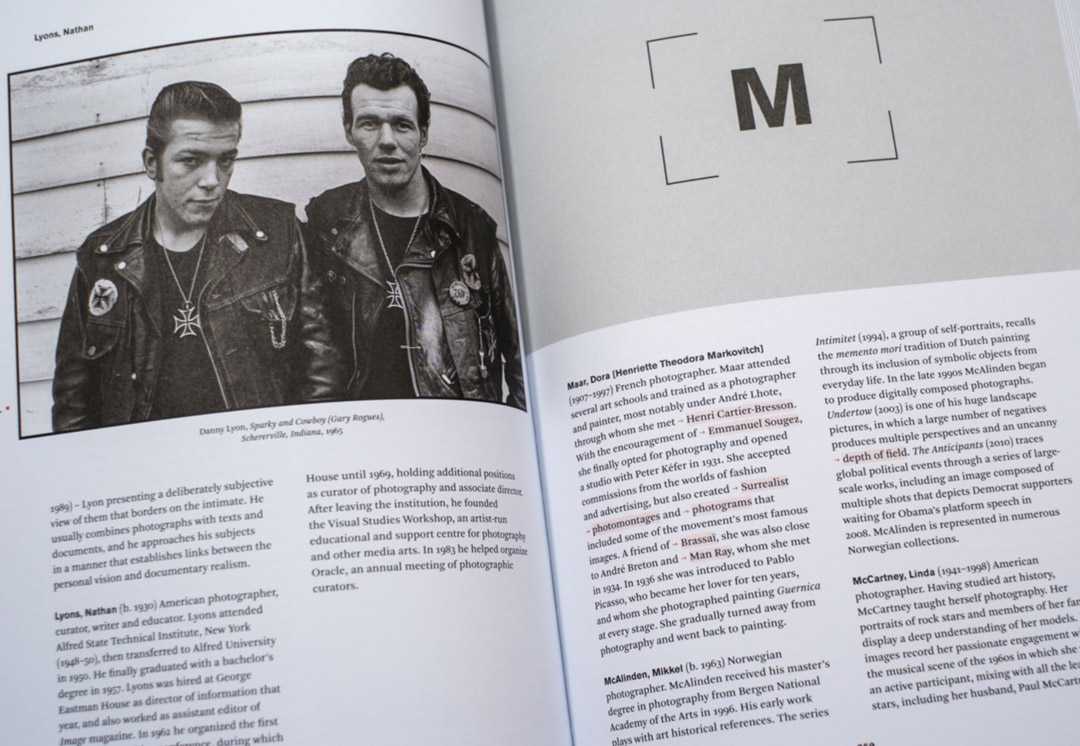

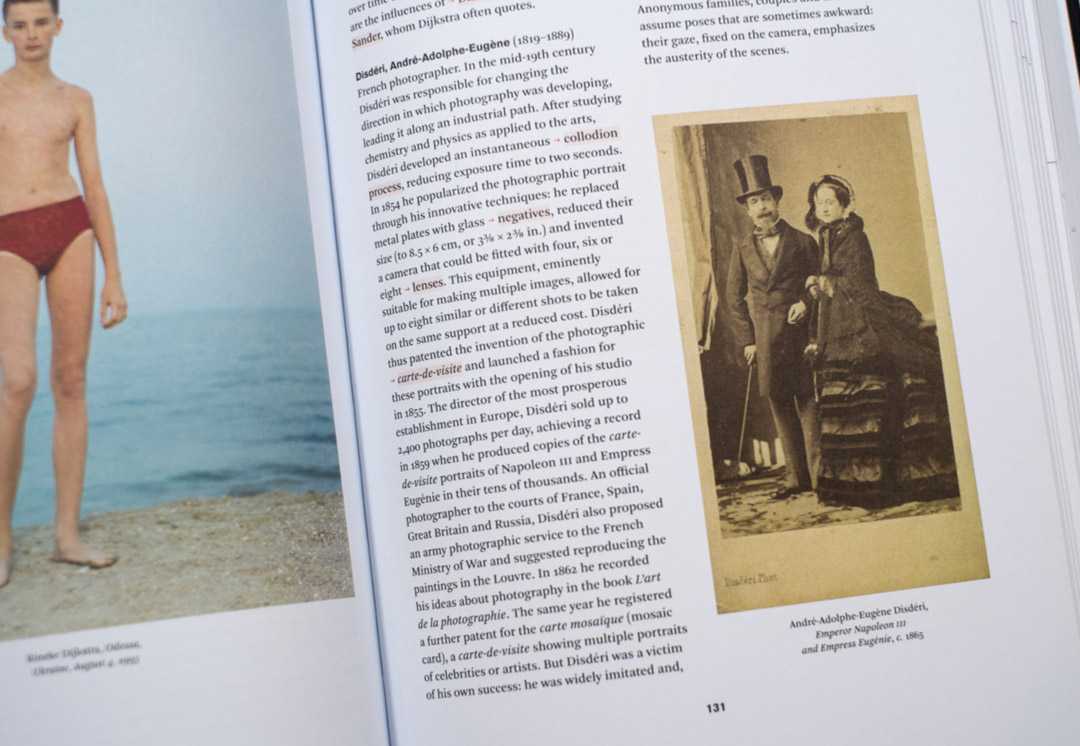

The ambition of Herschdorfer and the team of researchers is praise-worthy, as is the focused attention for the entries included, paring photography down to its essentials. Illustrated with 300 photographs and diagrams, the book also provides in brief form a visual introduction to the people and concepts at play. The ultimate outcome is somewhat questionable in value for generations far more accustomed to searching and skimming than using a desktop reference book for an idea already in the mind. For this reason, the dictionary seems most appropriate to a pre-digital audience, or those who determinedly prefer paper-based information.