Laura Chen

Nobody Home

Hardcover, silver foiling, 124 pages, 210 x 160 mm First edition of 100 signed copies

€ 40 / £ 35

“When someone is dying and you count down to someone’s last breath. To see the colour drain from the face of a loved one. To see the body still and calm after so much wretched pain and suffering, that is powerful. The silence lingers.”

British photographer Benjamin Hampson (b. 1988, North London) shares a poignant description of what it is like losing a person that is close to you in his self-published book ‘Nobody Home’, which documents the stages both during and after the passing of his father, who had been diagnosed with prostate cancer and Parkinson’s Disease.

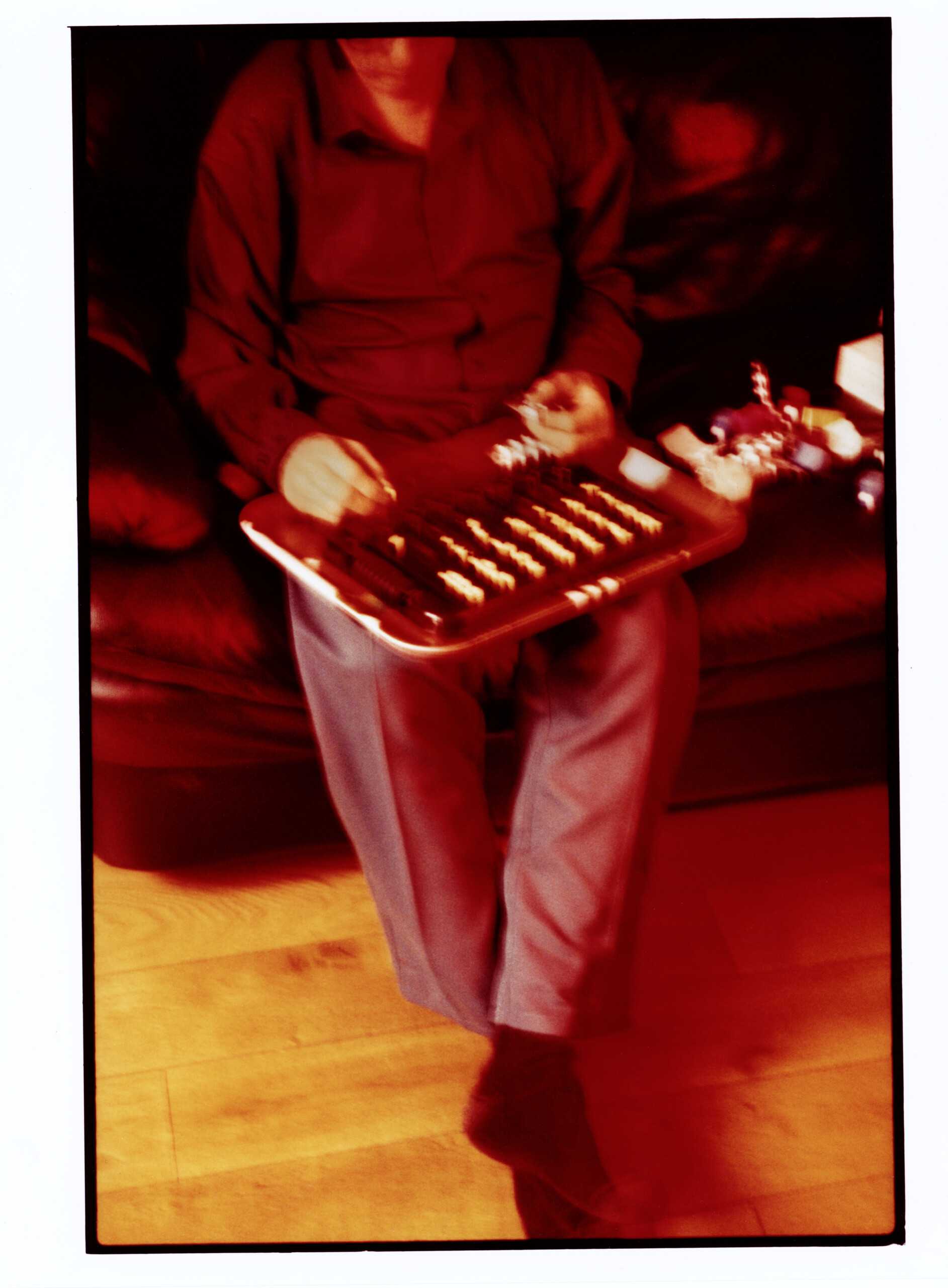

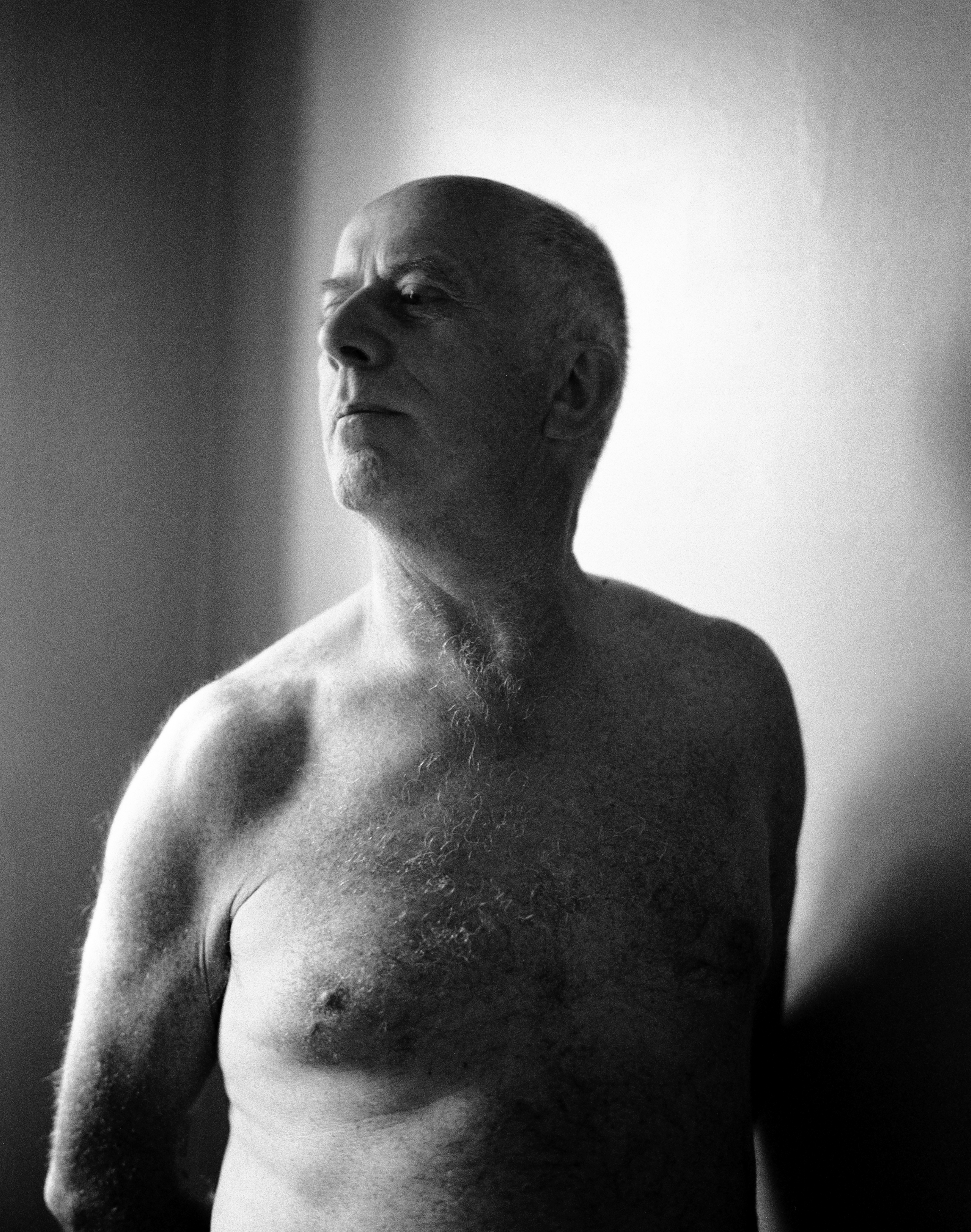

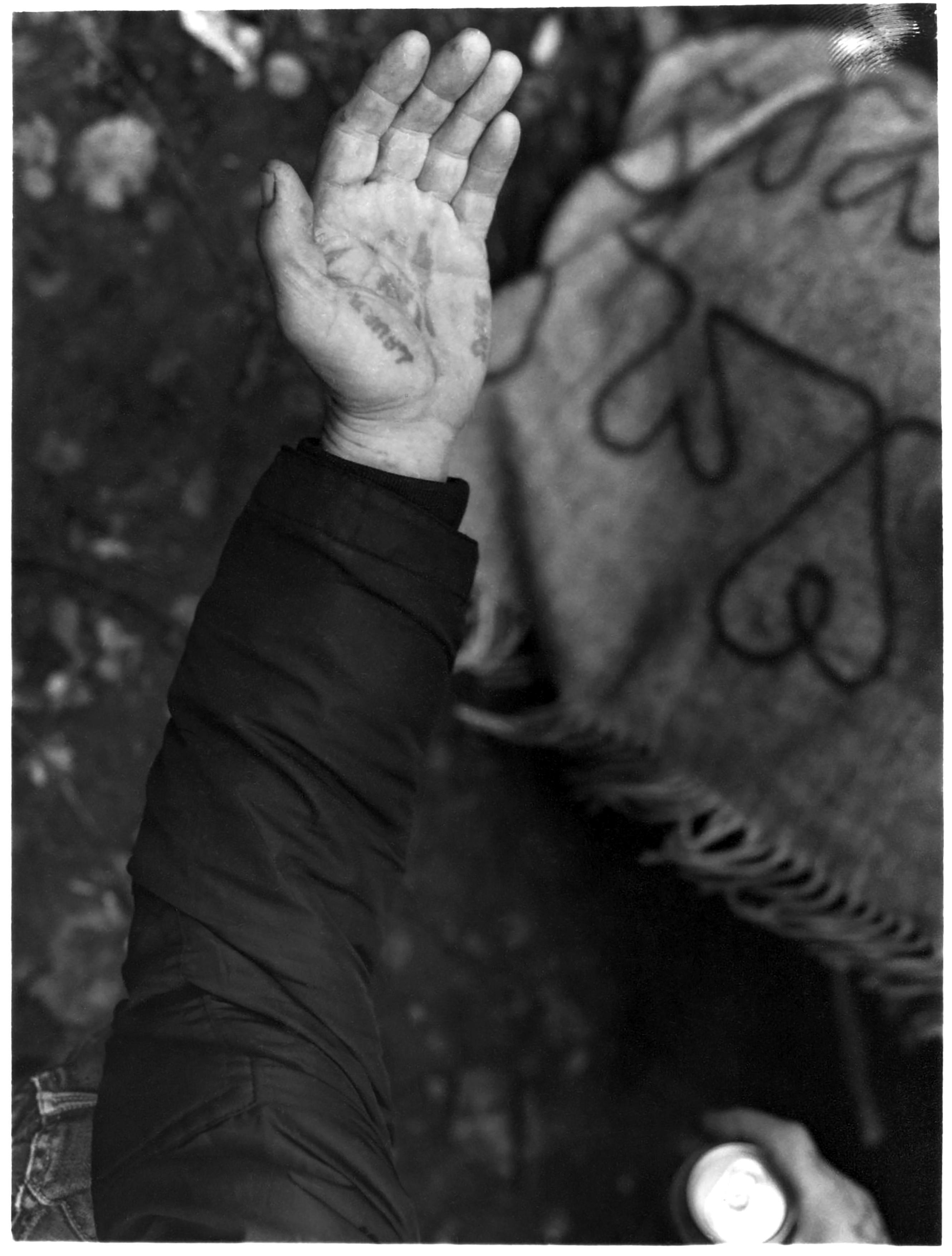

Using photographs and text from 2015 and 2016, the book is divided into four chapters that deal with the different ‘deconstructions’ within it. First, the deconstruction of his father’s physical being, as he was undergoing rigorous chemotherapy treatments and trying to cope with Parkinson’s — a diagnosis he found even more brutal and impactful than the cancer. A carpenter by profession, his arms and hands were his prized possession, so as they progressively became more stiff and uncontrollable, he lost confidence in his work, and the freezing episodes put him at risk of losing his driving license.

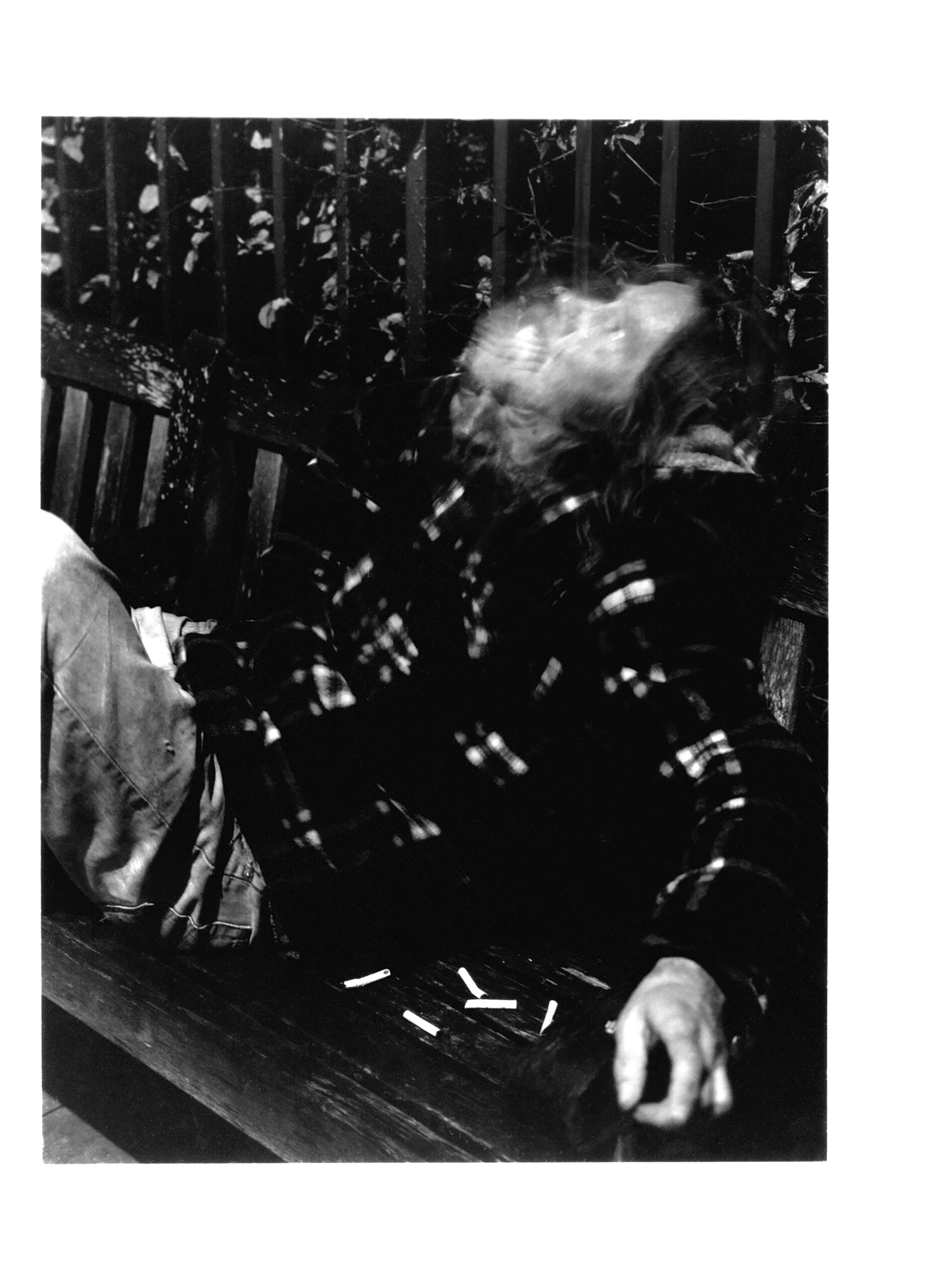

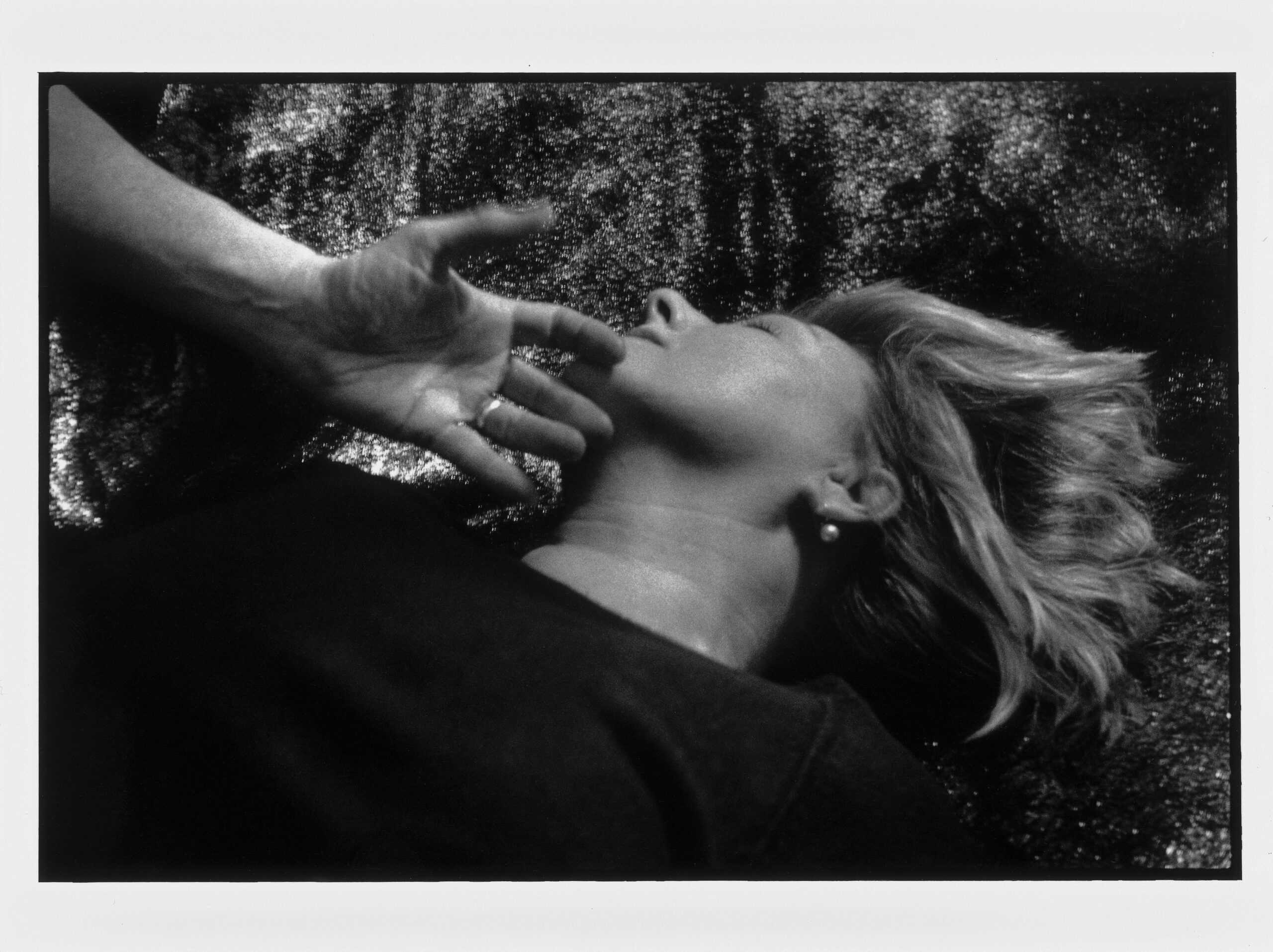

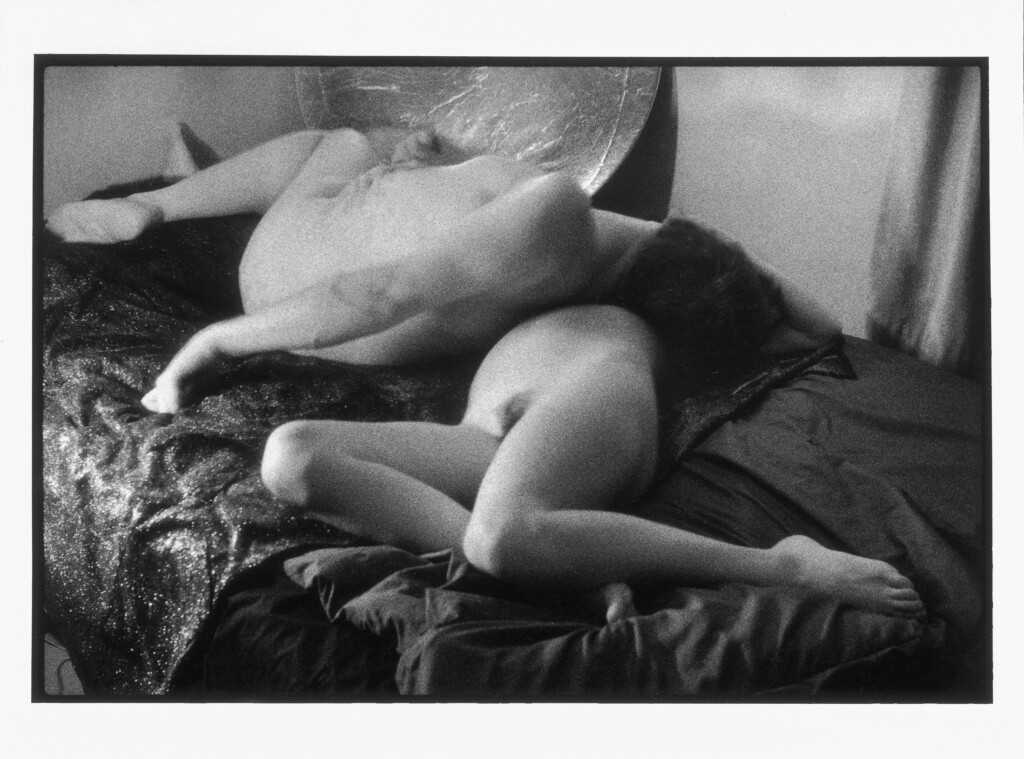

The second deconstruction is that of the photographer himself. “My father was my absolute hero. I was in despair. I was in pieces during this period. I sought solace in masochism and excess because I could not face the pain of seeing my father die. I saw death and religious iconography everywhere”, he writes in the preface. Around the time leading up to the death was Hampson’s frenzied expression and plea for help in 2016. He often met with people away from home in an enclosed private setting, photographing them and himself in a vulnerable state of mind. Bare bodies, acts of frustration, unfiltered dialogues, intoxication, addiction, and spiritual commonalities found in dark places — an abundance of intimacy and connection were all captured by his lens and translated into a series of melancholic images, some reminiscent of softly-blurred oil paintings, referencing sacred motifs.

“The world was muddy, and I was nihilistic.”

The process of surrounding himself with and talking to others who were dealing with similar experiences soothed him, as he searched for meaning. At the same time, his father had his own way of recording his mood and condition, by keeping a medical journal of his day-to-day dealing with illness. As recommended by the hospital, over the course of his death he broke down the experience of his body shutting down, in forced and painfully vivid diaristic accounts. These texts, which punctuate the images, form the third deconstruction in the book.

The last component is the medium of photography itself. “With each hand printed photographic exposure, with each chance to catch the essence of something that was being pulled away from me, I wanted tangibility and texture. The drapes thrown over the chairs in the living room. His workman’s yard – the metal and the rust. The nuts and bolts of a life falling apart.” Instilled with motion and emotion, many of the photographs are slightly out of focus, even shaky at times. Whether intentional or not, they resemble the physical and mental state his father was in; a metaphorical portrayal of his affected nervous system, as well as of Hampson’s own befuddled outlook at the time.

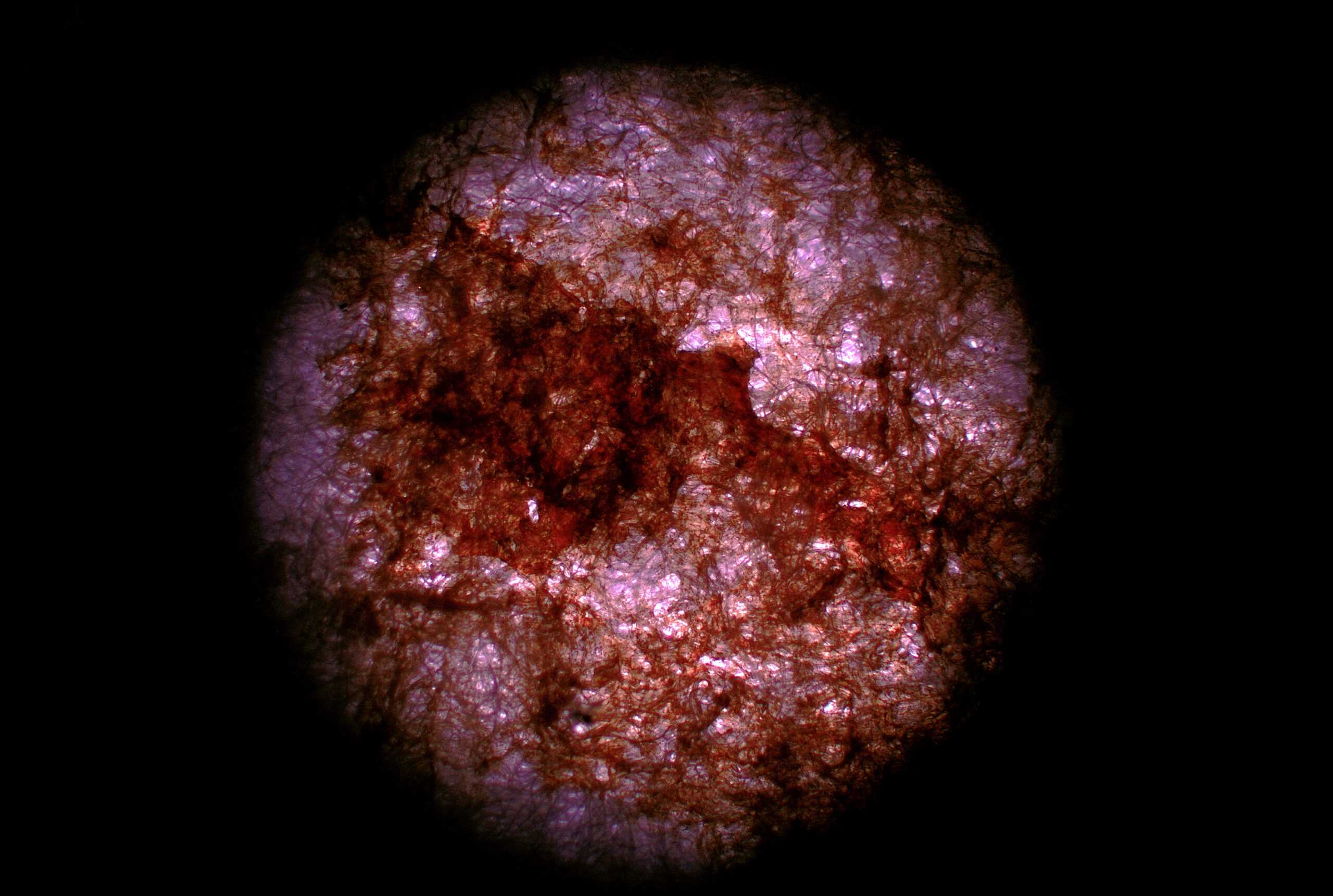

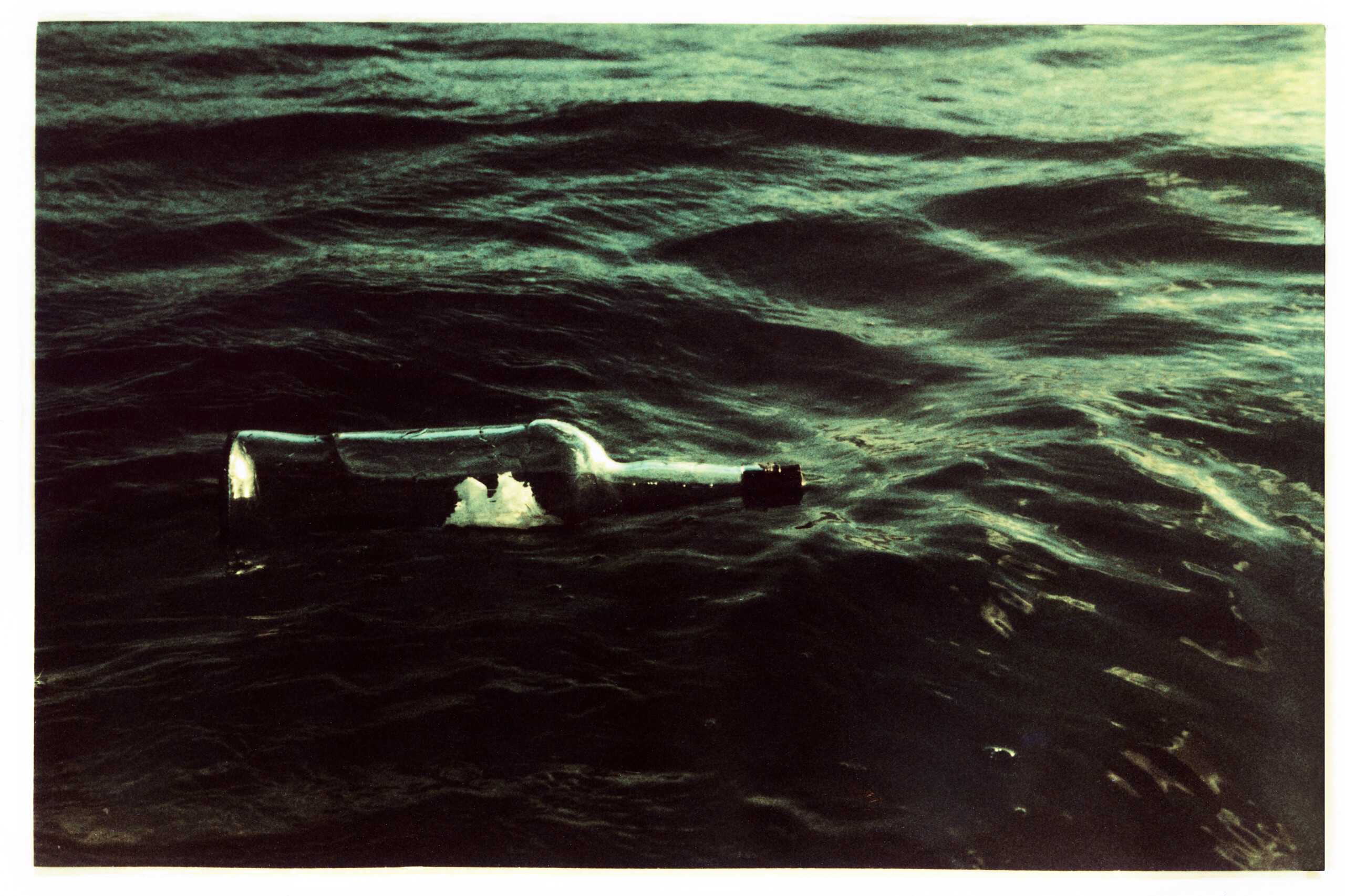

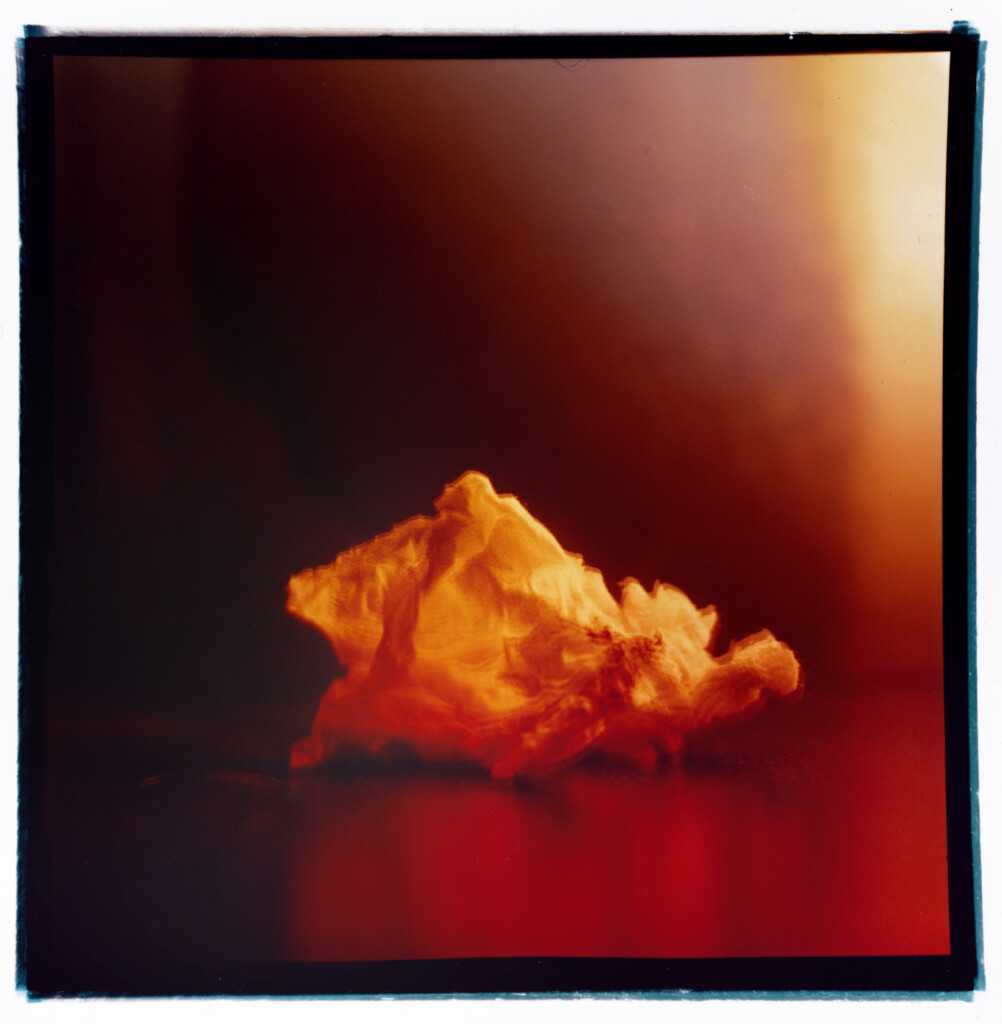

A year later when tidying things away, Hampson found a bloody tissue in his father’s dressing gown pocket that he kept and stored away in a 35mm film cassette. It moved with him from home to home, as a way of holding on. Wanting to find his father metaphorically in another world, in search of awe, he had the tissue forensically examined and photographed in a science lab. The otherwise tiny tissue came to life with fragments of his DNA magnified quite beautifully under the microscope; an essence of his existence in an abstract form. Hampson parted with the tissue in 2021, when he placed it carefully in a whisky bottle and set it out to sea. With this symbolic act, he set the memory free, closing both this chapter of his life as well as the final chapter of his book, which ends on a black and white photograph of the submerging bottle, disappearing into the sunset.

Dividing the 124 pages, each chapter is indicated by a traditional carpentry marking. With every ‘deconstruction’ — a building trade term for dismantling something so that the individual elements are kept for reuse, rather than discarded — the relationship between image and text becomes stronger as the pieces of Hampson’s broken world reassemble. In literary terms, the definition of ‘deconstruction’ means a way of analyzing language that assumes that text cannot have a fixed meaning. Likewise, images do not have a single or fixed reading, but instead, leave room for infinite interpretation. In ‘Nobody Home’ image and text coexist, giving meaning to one another, while constantly breaking and making up their structure.

![]() Benjamin Hampson is a photographer with a documentary approach and interest in large scale hand printing. He works across a broad range of advertising, editorial and commercial projects with an objective to empower people through the art narratives he creates.

Benjamin Hampson is a photographer with a documentary approach and interest in large scale hand printing. He works across a broad range of advertising, editorial and commercial projects with an objective to empower people through the art narratives he creates.

Order ‘Nobody Home’ here.