Linda Zhengová

45

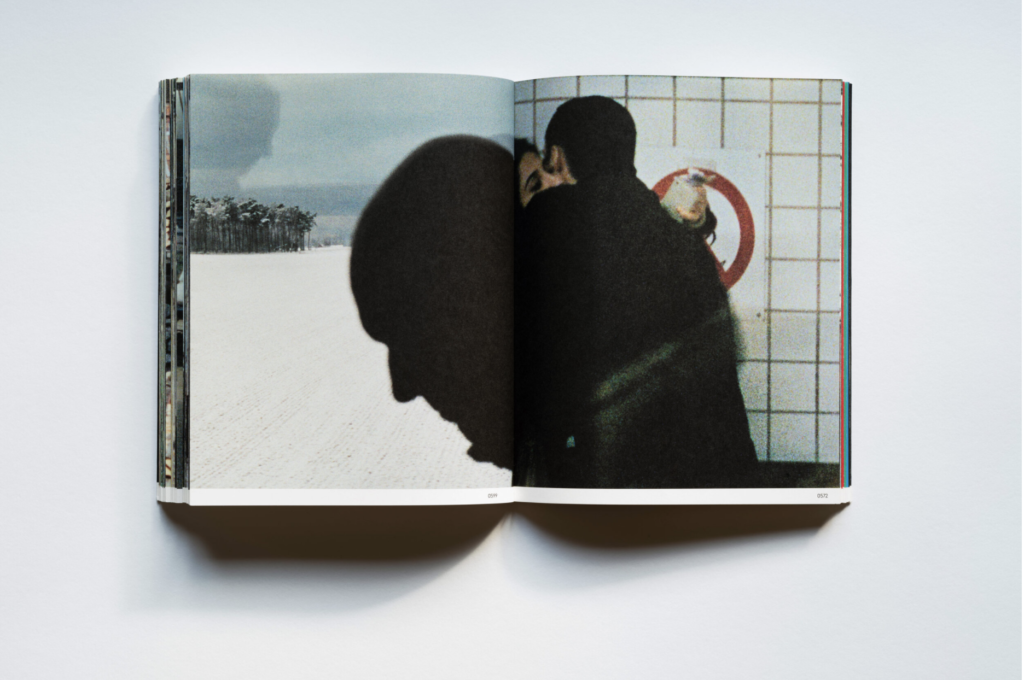

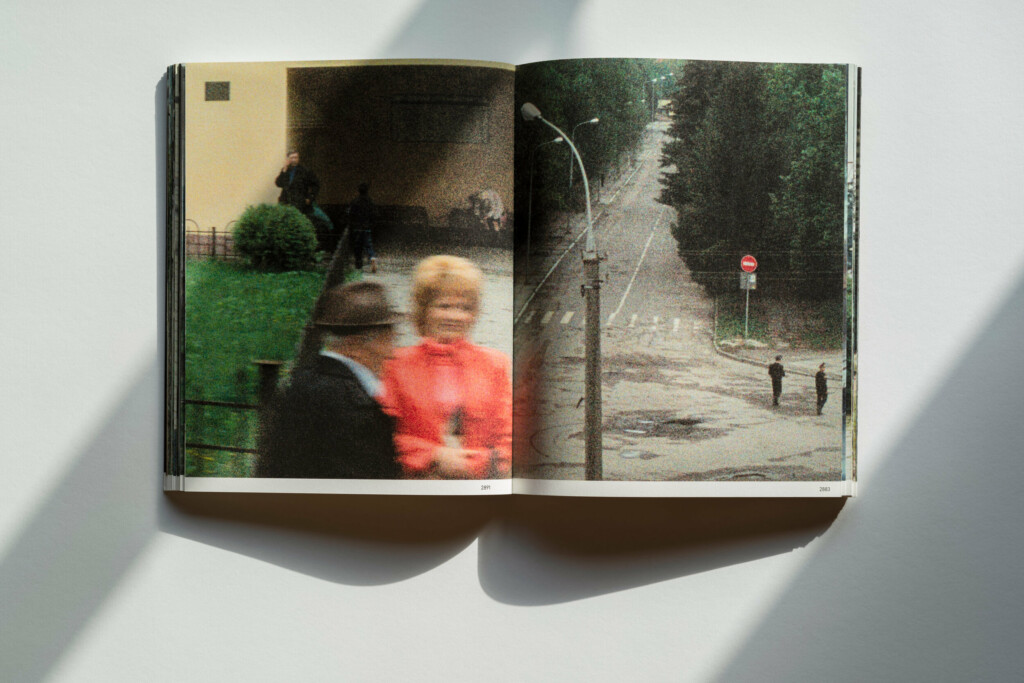

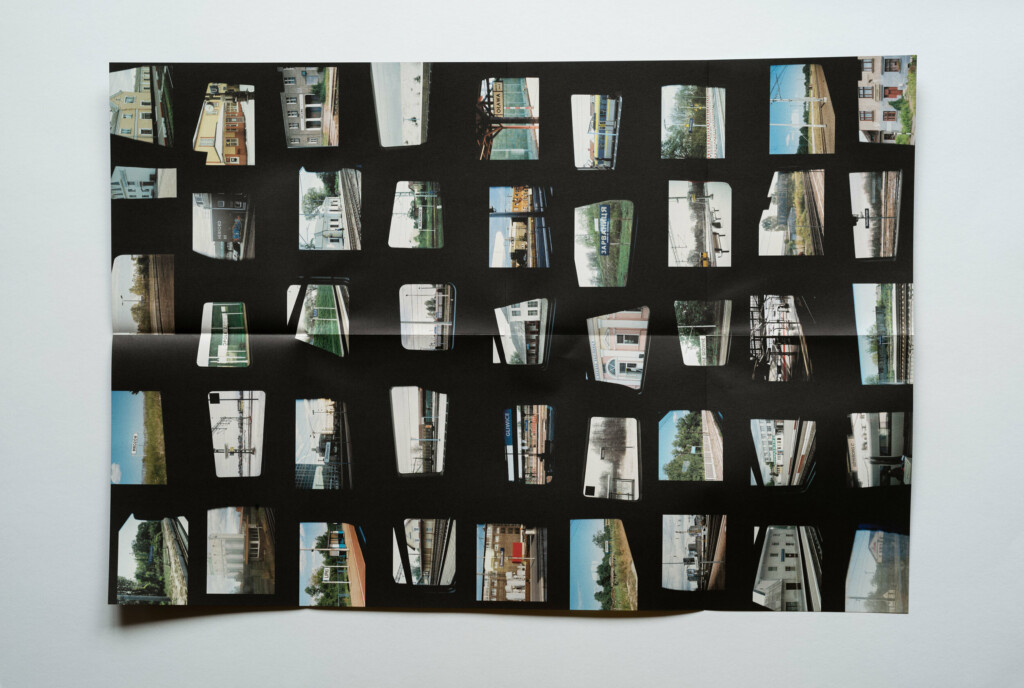

Paperback with Japanese fold Includes large-format fold-out poster 22.5 x 28 cm, 120 pages

€30/ £25/ $40

Damian Heinisch (b. 1968, Poland/Germany) is an Oslo-based artist who grew up in Germany, where he completed his MA in Visual Arts at the Folkwang School, Essen. Recently, he also won the MACK’s First Book Award 2020 for his project ‘45’.

In 2013, Heinisch travelled from Oslo to Ukraine by train to follow the journeys once taken by his relatives.

In 1945, his grandfather disappeared from Gliwice, Poland. He was among the men taken by train to a labour camp in Ukraine. In 1978, Heinisch’s father left Gliwice together with his family in order to start a new life in West Germany. Coincidentally, during all three of these journeys, each man (Heinisch’s grandfather, father and Heinisch himself) turned 45.

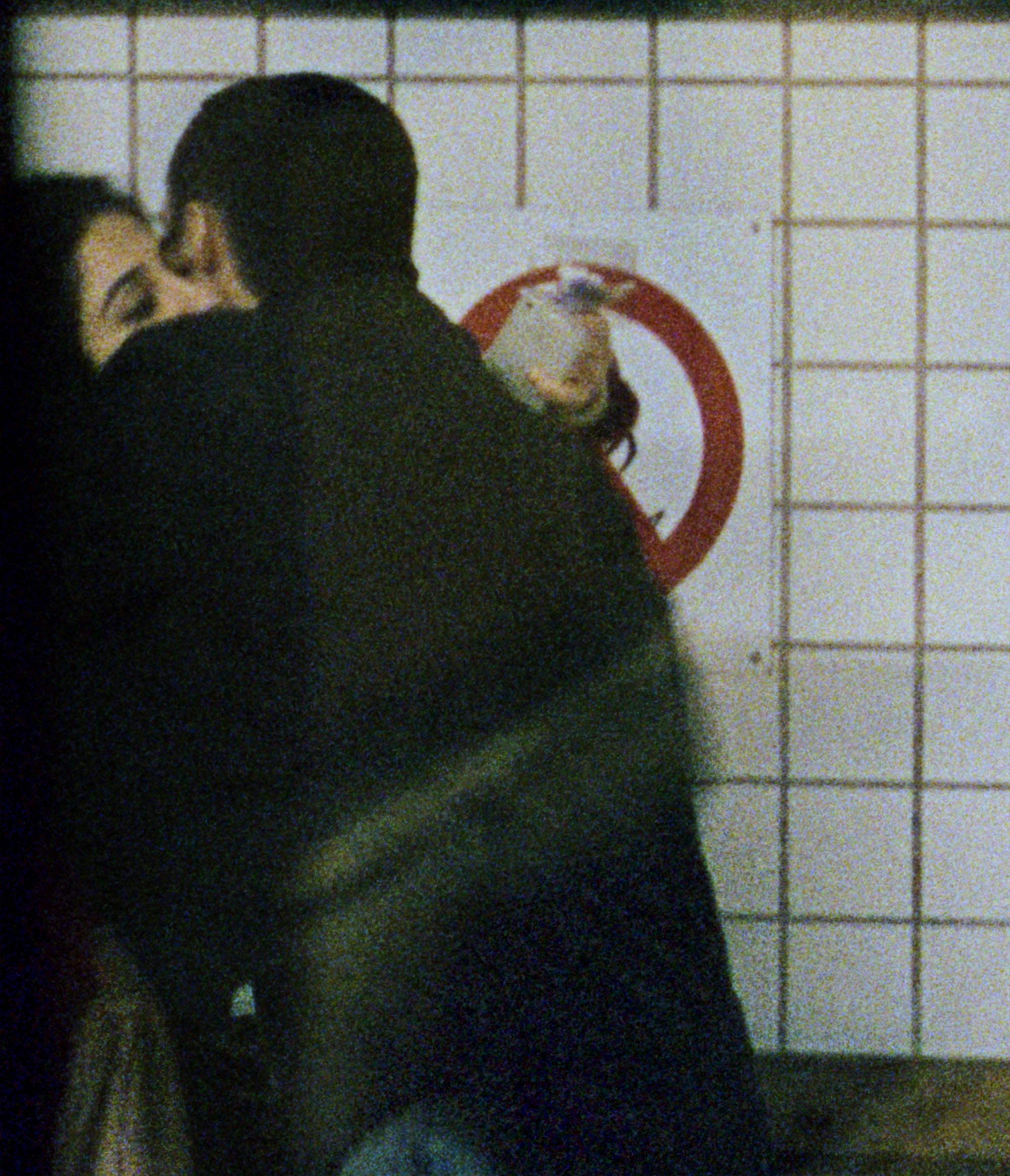

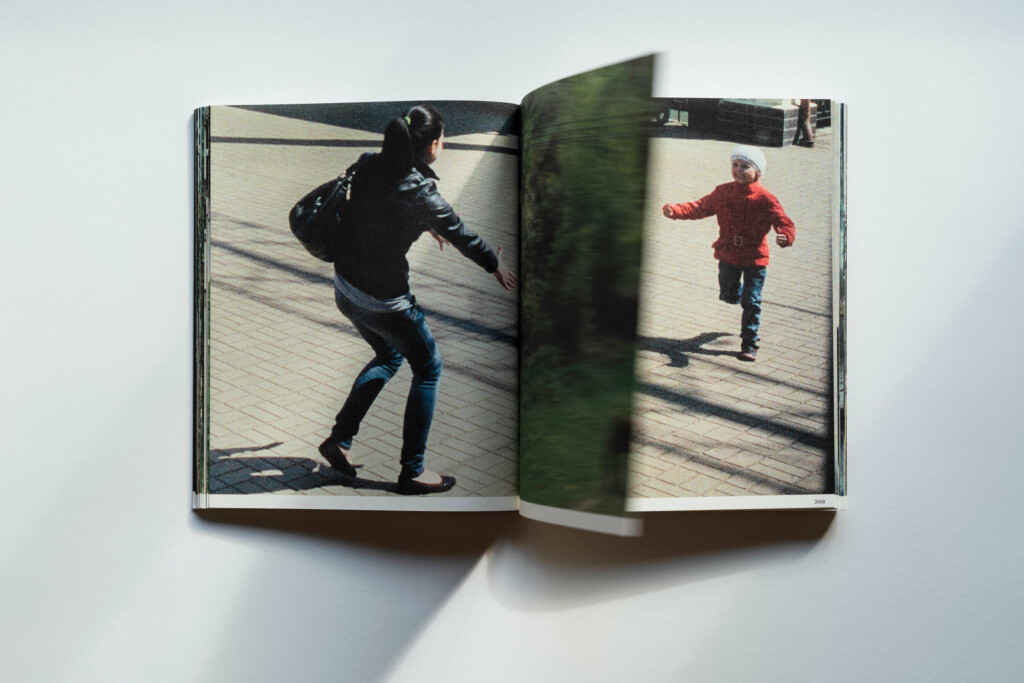

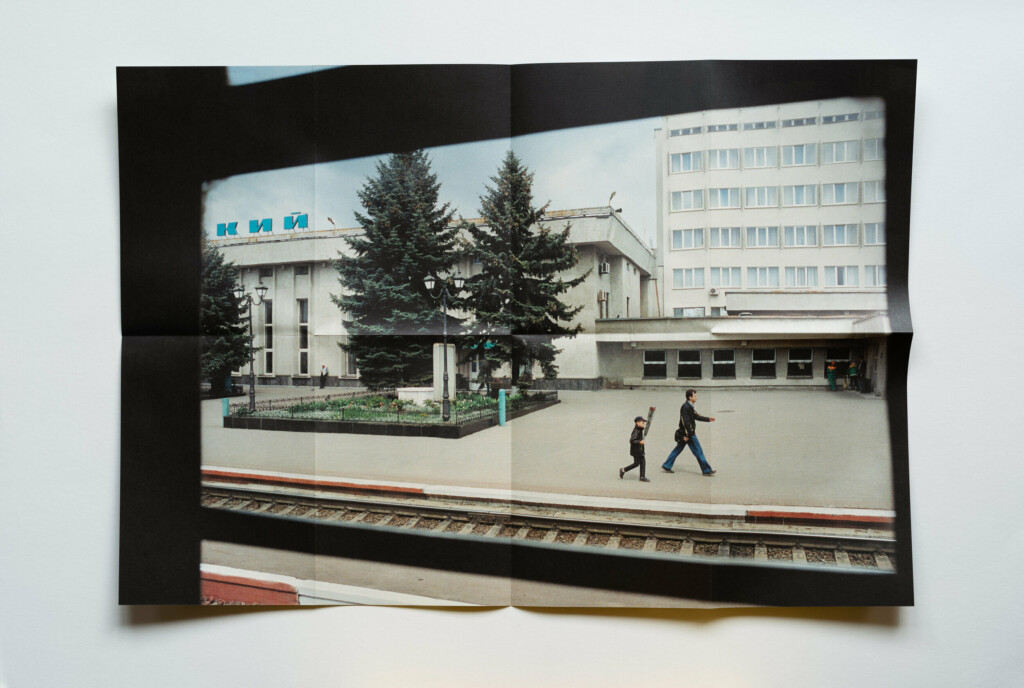

In his book, Heinisch presents fragments of images that highlight the presence of humans in their physical surroundings when captured from train windows. It includes numerous texts in the form of excerpts from his grandfather’s diary, an account of his family leaving Gliwice in 1978, and an artist statement by Heinisch.

Addressing the issues of forced migration alongside his own family history, ‘45’ is an introspective journey into our memories and their relation to the present. In an interview with GUP, Heinisch talks about the process of making ‘45’ and his family history.

Inspired by journeys made by multiple generations of your family, you yourself travelled by train along the same routes. How did it feel to revisit such places?

Given that I was working on a long-term project focused on my family’s history in the context of the Second World War, it was inevitable that I would visit my grandfather’s unknown grave in Ukraine. I travelled and worked in four European countries – Ukraine, Germany, Poland and Norway. Each of these areas represents a different epoch in my family’s history and the historical timeline.

The chronology begins in 1945, when both of my grandfathers disappeared from Gleiwitz (its German name until 1945) in Upper Silesia along with countless other men. They were taken by train to a labour camp in Ukraine. One of them returned a year and a half later, while the other died in the city of Debalzewo. His grave is unknown and all that remains is a small diary he wrote throughout his deportation. In 1978, following a lengthy existential struggle and forced political unemployment, his son – my father – left Gliwice (its Polish name from 1945) with his family to start a new life in West Germany.

I understood that my family’s lives had been considerably influenced by forced immigration, and that trains had played a significant role in the process of resettlement. After reading my grandfather’s diary, I decided that I would be the first family member to visit the area of eastern Ukraine in which his unknown grave is located. I wanted to understand my family background, and in doing so, to try to understand where I come from.

It felt natural to take the train from my hometown of Oslo to the other three regions, and this is when I had the idea to document my own journey. The train window became the stage. I found myself with my 35mm camera pressed to my face, collecting impressions of present-day Europe.

Upon reaching the city of Debalzewo in eastern Ukraine, I looked for an authentic and beautiful graveyard, and chose one grave out of many hundreds as his symbolic final resting place. I left some red and white flowers there. And I called both of his children – my father and my aunt. When my father picked up and I heard his voice, I felt a sense of change and closure – in a positive way.

After I returned from Ukraine in 2013, the material disappeared into my archive and I looked over it again when time allowed. I saw great potential for the material to become a book and embarked on an unexpected experiment. In 2017 I joined a photobook workshop led by Nicholas McLean and Alessandro Calabrese. The workshop cumulated in the production of a dummy and the participants were asked to challenge the book as a format. This is when the basic concept for ’45’ was developed, and subsequently refined.

“(…) my family’s lives had been considerably influenced by forced immigration.”

“The train window became the stage.”

In ‘45’ you present grainy images shot on your 35mm film camera. Why did you opt for such a visual strategy?

’45’ is my first book and each stage of the production process was intense. The original material was photographed with the train window framing the scenery. The poster supplied with the book is the only evidence of the uncropped work. The original film material became part of an installation based on slide projection, allowing me to approach the book in a different way.

Ultimately, this was an experiment with an almost unknown outcome. The book dummy was designed as a kind of a riddle. I was surprised to find myself intuitively fragmenting my work in order to get closer to the human aspects – a higher level of abstraction associated with surveillance, veiled in a layer of noise. Through this, I hope to leave the viewer with an instant and existential feeling. The book is full of hidden implications touching on themes of melancholy, longing, sorrow, but also humour and sarcasm. The narrative is set, but its interpretation will always be based on the individual’s life and cultural experiences. I wanted to leave it open.

In the end, I embarked on three journeys; first the physical journey, holding my 35mm camera to my eye for hours on end. This led to the second journey into my developed films, confronting my findings and contrasting them on the pages of the book. The final journey led me into the virtual world, mapping the train tracks kilometre by kilometre on Google Maps all the way from Oslo to Debalzewo. Again, the collecting of numbers supports the idea of a riddle and reflects the insidious methods by which people have historically been dehumanised – reducing them to numbers and transporting them like cattle.

Consequently, a number was also used for the title of the book. At some point in all three train journeys, each family member turned 45.

“(…) this was an experiment with an almost unknown outcome.”

“At some point in all three train journeys, each family member turned 45.”

What were the crucial decisions you made while sequencing and editing the book?

The book edits followed an obvious logic but were also time-consuming and challenging. The first issue was the sequence. Since all images were taken chronologically throughout the journey, it seemed apparent for the book to follow the same pattern. As the trigger for this cathartic journey, Ukraine felt like the natural place to start the book, even if the original journey pointed in the other direction.

I was left with over 4,000 35mm colour images but had limited space on paper. With each image, I carefully investigated the possibilities of fragmentation compared with the following image. Most of the pages in the book feature a pairing selected intuitively on the basis of memory associations. The visual connection is strengthened by the introduction of individual points shared by both image fragments.

The Japanese binding was not chosen solely for its aesthetic value. It allowed me to place selected images over several pages and leaves the viewer with a feeling of travel and continuity. Texts based on the journeys of each family member, which come later in the book, complement the image sequence and to help solve the puzzle.

Since ‘45’ reflects on your personal family history as well as forced immigration in Europe, what would you say is the main goal of your book?

Although my journey was motivated by events in my own family, I hope its narrative can help to raise awareness of universal questions. Countless families in Europe lost their loved ones through deportation and endured similar immigration and resettlement processes – and this continues to this day. The book’s imagery confronts the viewer with impressions of present-day Europe and the narrative may provide an opportunity to understand a forgotten part of our common history.

It seems Europe has healed its wounds after the Second World War. Countries that suffered mass destruction were rebuilt and societies returned to a new structure. And yet a feeling of shame has been passed on from generation to generation, influencing our everyday lives and decisions.

Our times are being shaped by a political shift to the right… Try as we might to deny it, we have refugee camps in Europe full of people waiting for a new life. We live in turbulent times and should be consciously observing our environment. Eight months after I returned from my journey, a new conflict erupted in the Donetsk region, leading to an ongoing war…

“(…) the narrative may provide an opportunity to understand a forgotten part of our common history.”

“(…) a feeling of shame has been passed on from generation to generation.”

The release of ‘45’ coincides with an exhibition at Webber Gallery, London, starting from 4 November 2020.