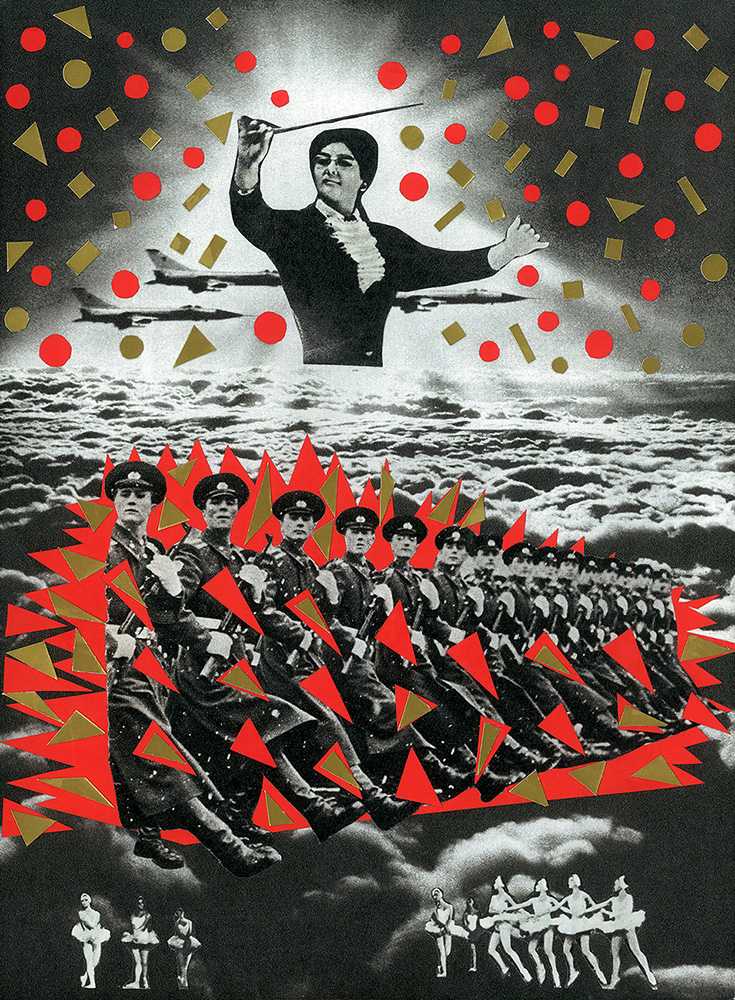

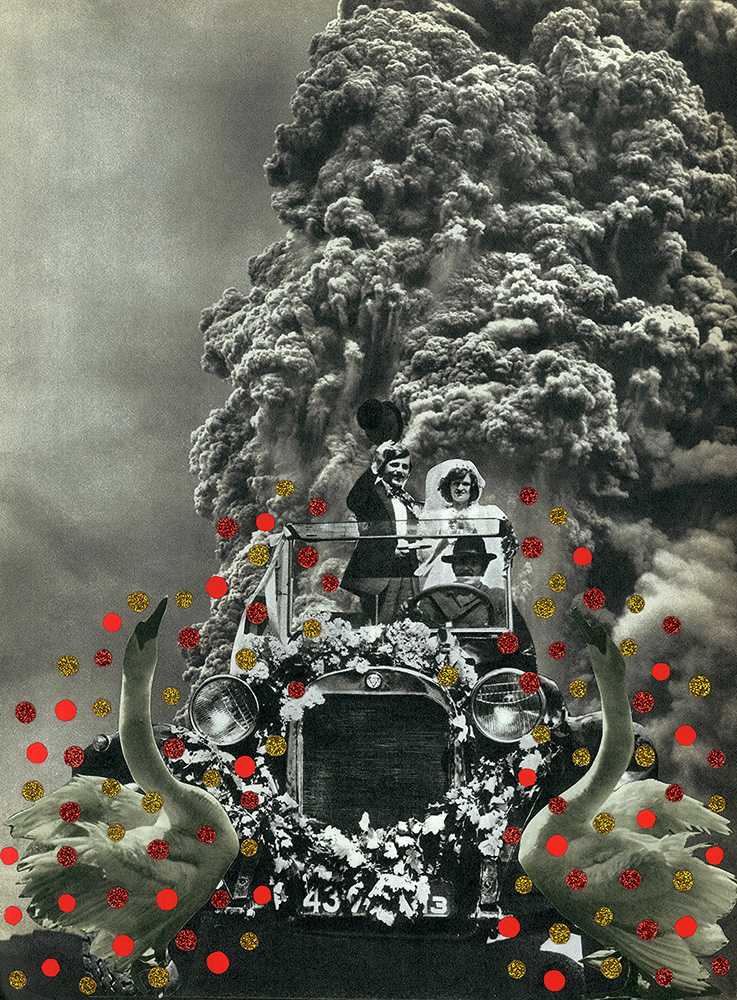

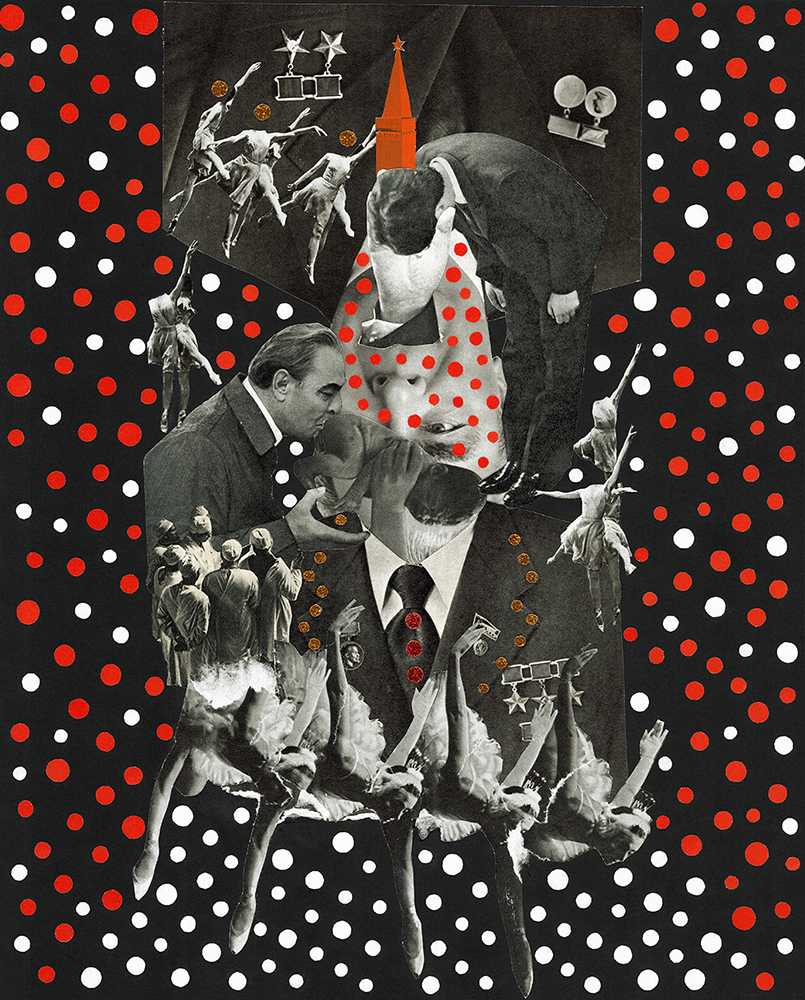

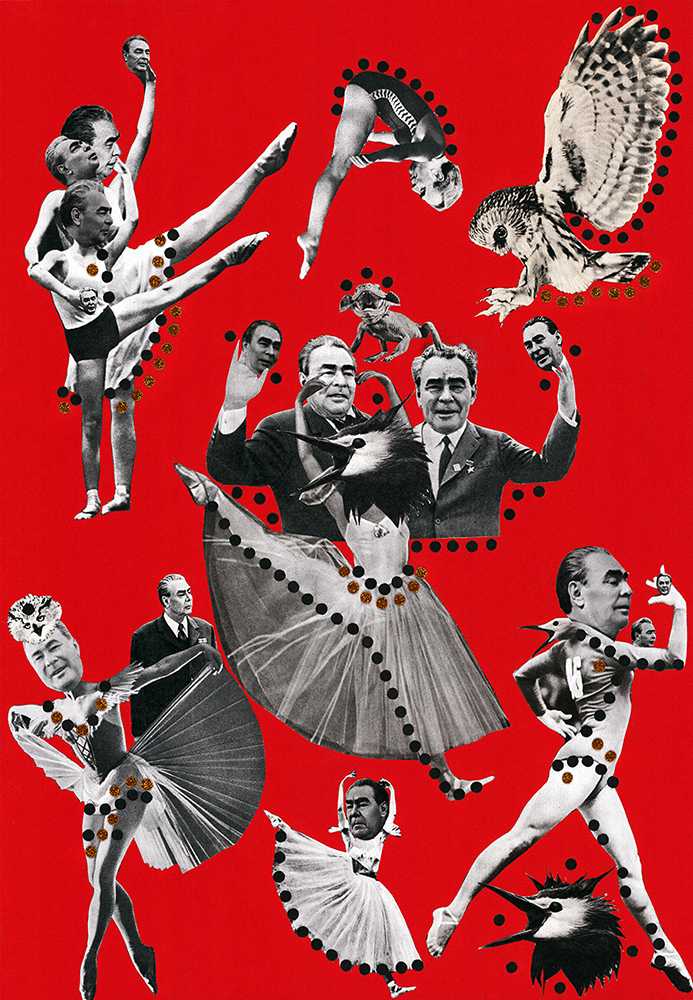

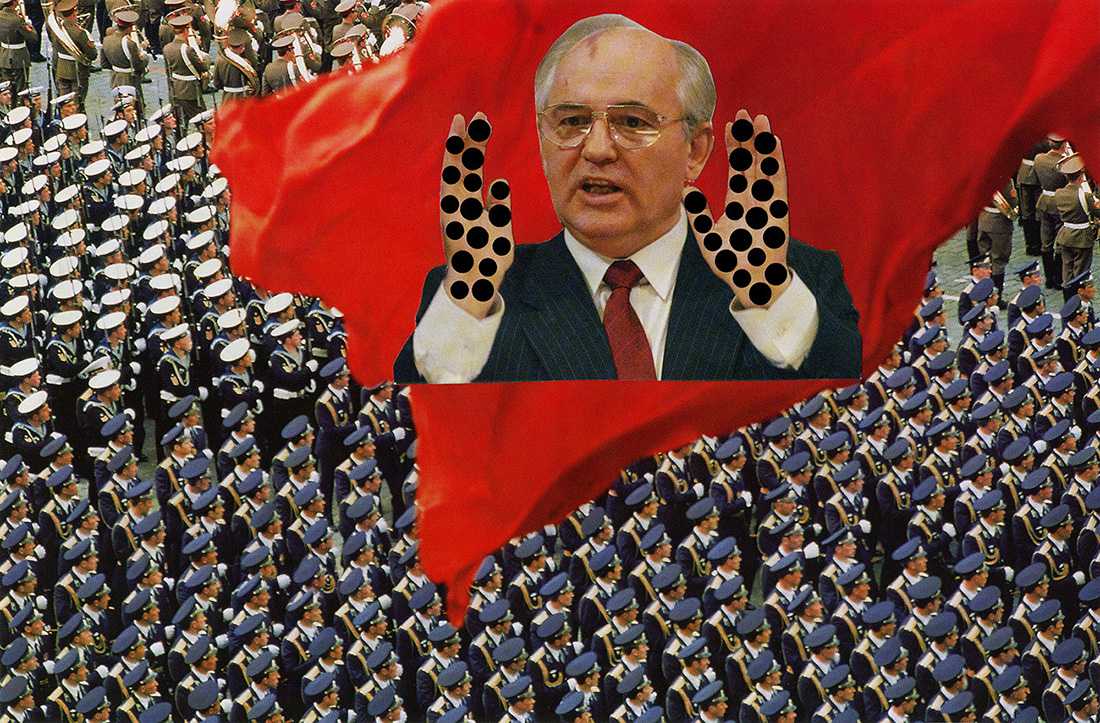

Masha Svyatogor (b. 1989, Belarus), a visual artist currently based in Minsk, primarily works with the medium of photography. The title of her series ‘Everybody Dance!’ is a reference to a phrase exclaimed in the Soviet comedy film ‘Ivan Vasilievich: Back to the Future’, directed by Leonid Gaidai. But it also refers to her own playful meddling with Soviet symbolism, inviting viewers to experience a visual ‘dance of elements’ – so specific for how the Soviet culture, its peculiar legacy, has been communicated and archived over the years.

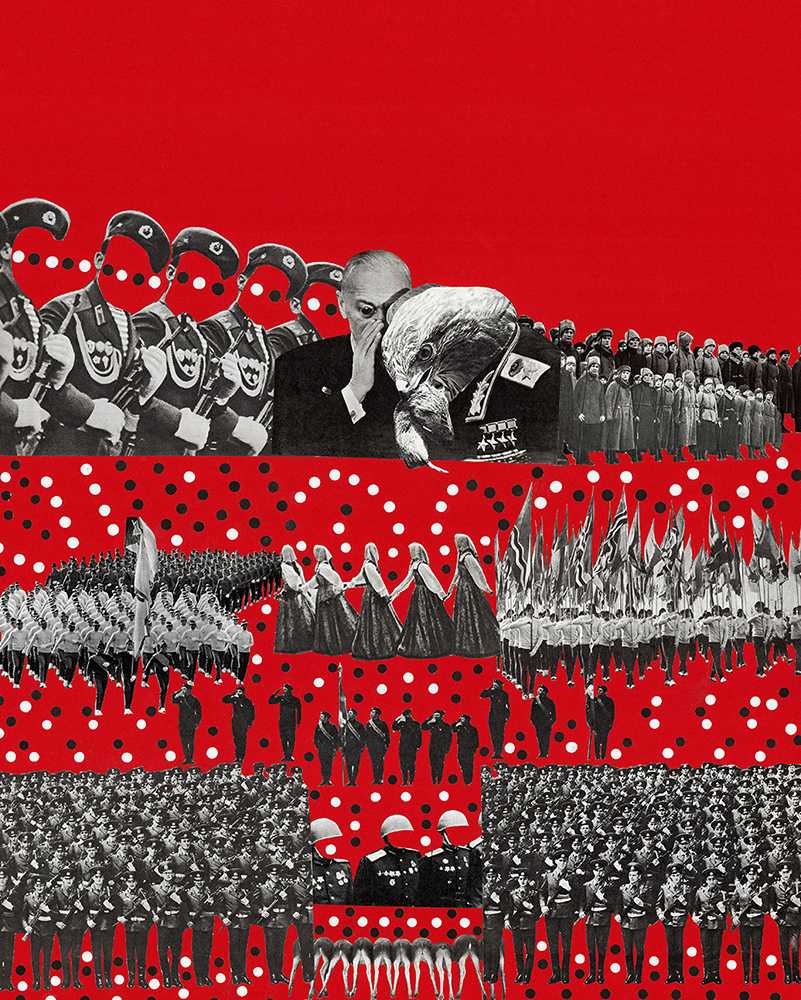

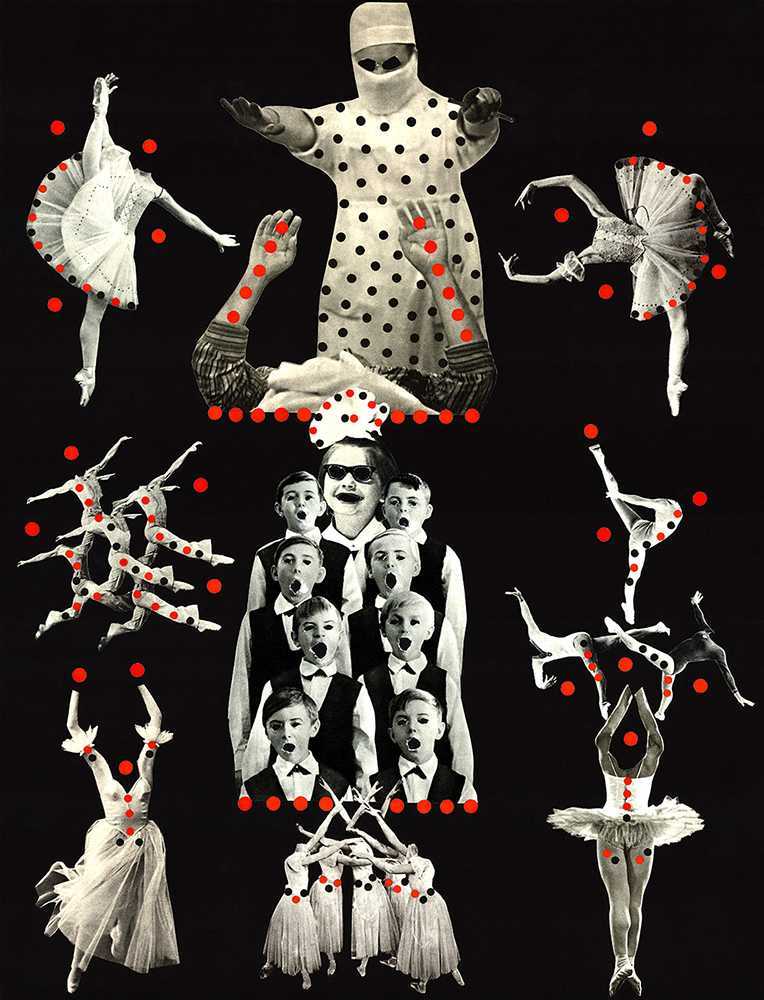

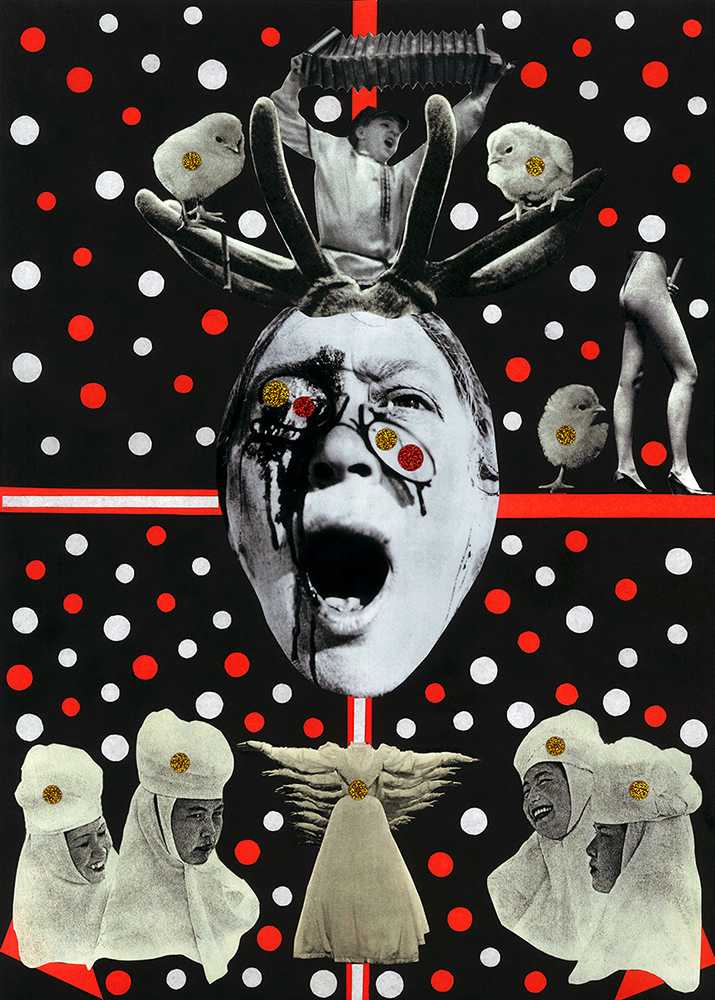

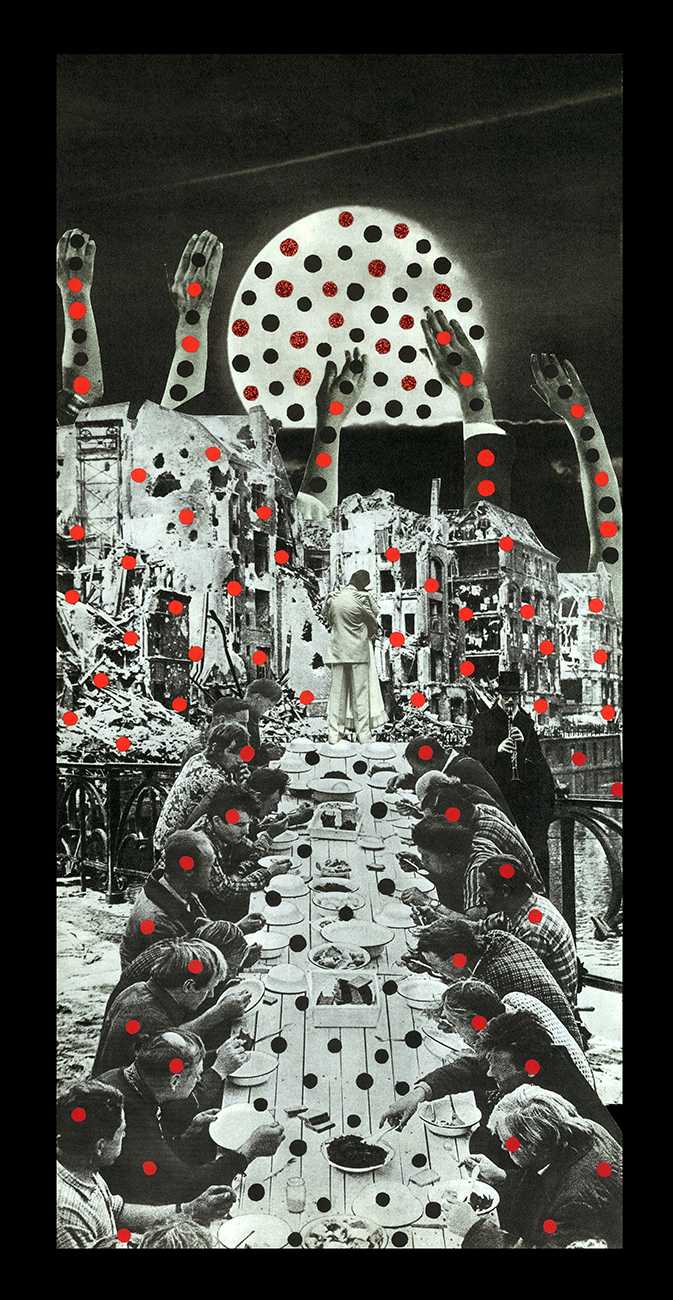

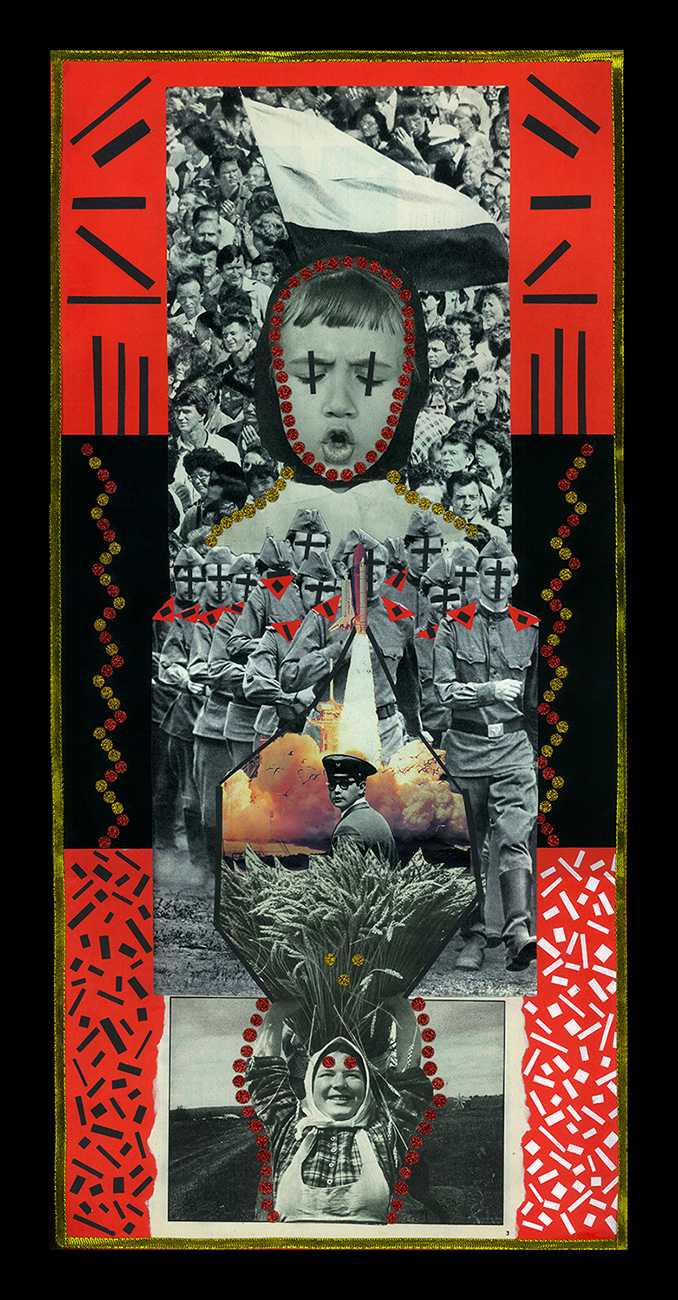

Svyatogor’s process is one of disassemblage: ‘official’ images of the time, politically loaded, are taken apart and formed into ornamental and surreal imagery. This is a conscious appropriation of the photomontage technique as it appeared in Russia and Europe during WWI, when Vladimir Lenin declares that photography is a super-powerful propaganda tool in a country where 70% of the population cannot read.

‘Everybody Dance!’ is a multi-dimensional and layered narrative of that historical span, which comes in complete contrast to official representations and their logic. That is, her images are manually constructed photomontages that feature cut-outs from Soviet magazines, yet her technique connotes the regime’s fabrication of history on a meta-level.

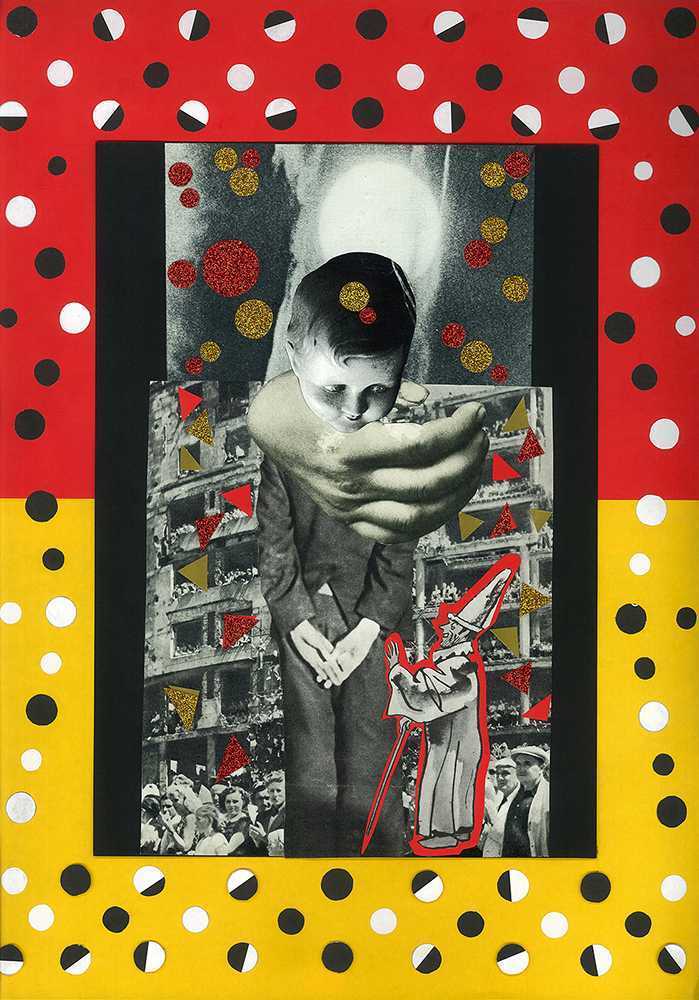

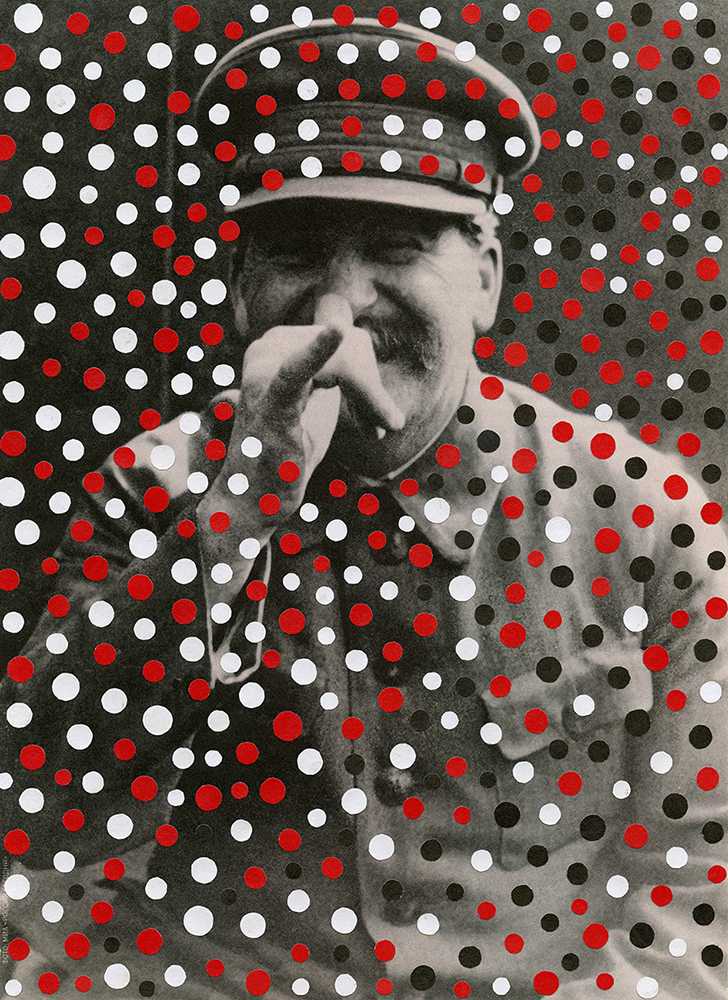

The heavy red colour that spreads among the surface of the artificially construed photographs, for example, is a clear reference to the Soviet flag. But Svyatogor uses it rather lightly. These postmodern montages rather function as a cheerful echo of the ‘original’ propaganda and the red is now mainly an aesthetic tool to connect various elements in the series.

Throughout the series, boundaries surrounding the concept of ‘the Soviet’ are surpassed. The viewer is confronted with artefacts of Soviet heritage in the form of street names, monuments, suburbia, and cinematography but the way of presentation – suggestive of the gaps and inconsistency that highlighted the Soviet period – is de-establishing the existing hierarchies that surround the common understanding of the USSR. Clearly, this is not a version of it that Yosef Stalin would have approved.

This project can be seen during the occasion of Circulation(s) Festival 2020 in March.