Los Angeles-based artist Robert LeBlanc is a self-taught photographer with an aptitude for capturing non-traditional communities. From firefighters to hurricane survivors, his images of life lived on the fringes of society offer an eccentric glimpse into otherwise rarely-pictured social spaces and events. In his latest project GLORYLAND, he continues to explore his fascination for the strange and unusual. For more than five years, LeBlanc documented a uniquely American subculture: one of the few remaining Holiness serpent-handling churches of West Virginia.

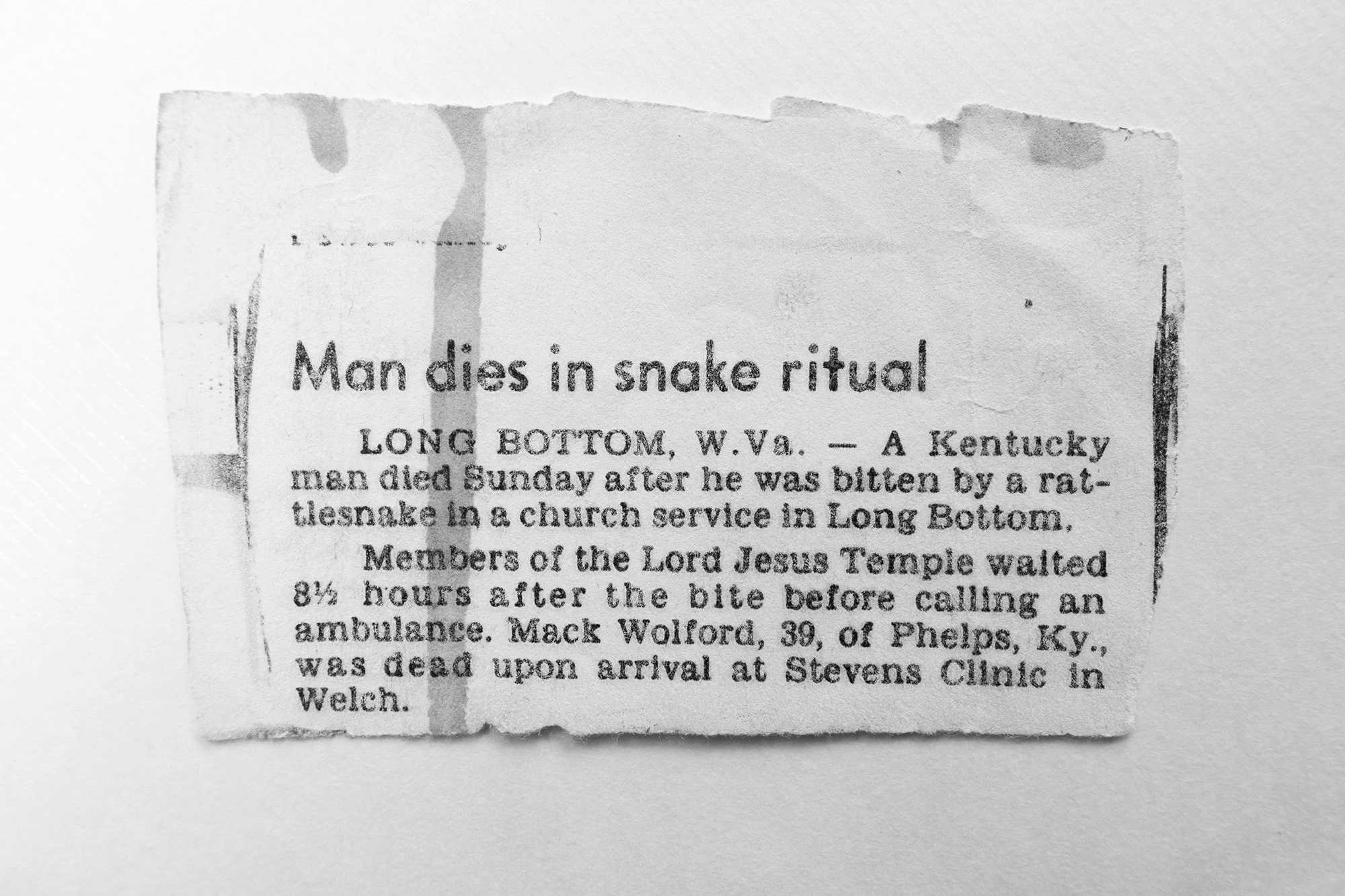

In the Appalachian Mountains, in the only state in the USA where snake handling is not outlawed, one can hear the sound of rattling and hissing fill the air. Every few miles, the bare, open landscape is interspersed by a handful of wooden homes and churches. Deeply rooted in the region, the presence of religion prevails and can be felt as one drives down the rugged and rocky roads. Once arrived in Squire, a quiet and humble town of no more than 300 residents, The House of the Lord Jesus takes centre stage. Outwardly, the building looks no different to any other Christian church seen along the way. Inside, however, a small yet devoted Pentecostal congregation worship old mystic snake rituals, led by Pastor Chris Wolford.

The Methodist revivals that took place in 1867 marked the beginning of the Holiness movement. Initially put out by John Wesley in the 18th century, a believer’s conversion is marked by two religious experiences that are necessary for salvation: justification and sanctification. In the 20th century came the introduction of a third “blessing” to signify one’s baptism by the Holy Spirit, one that strictly adheres to the very embodiment of the Word, such as Mark 16:17-18 — which includes drinking poison, speaking in tongues, handling fire and venomous serpents without risk of harm or death.

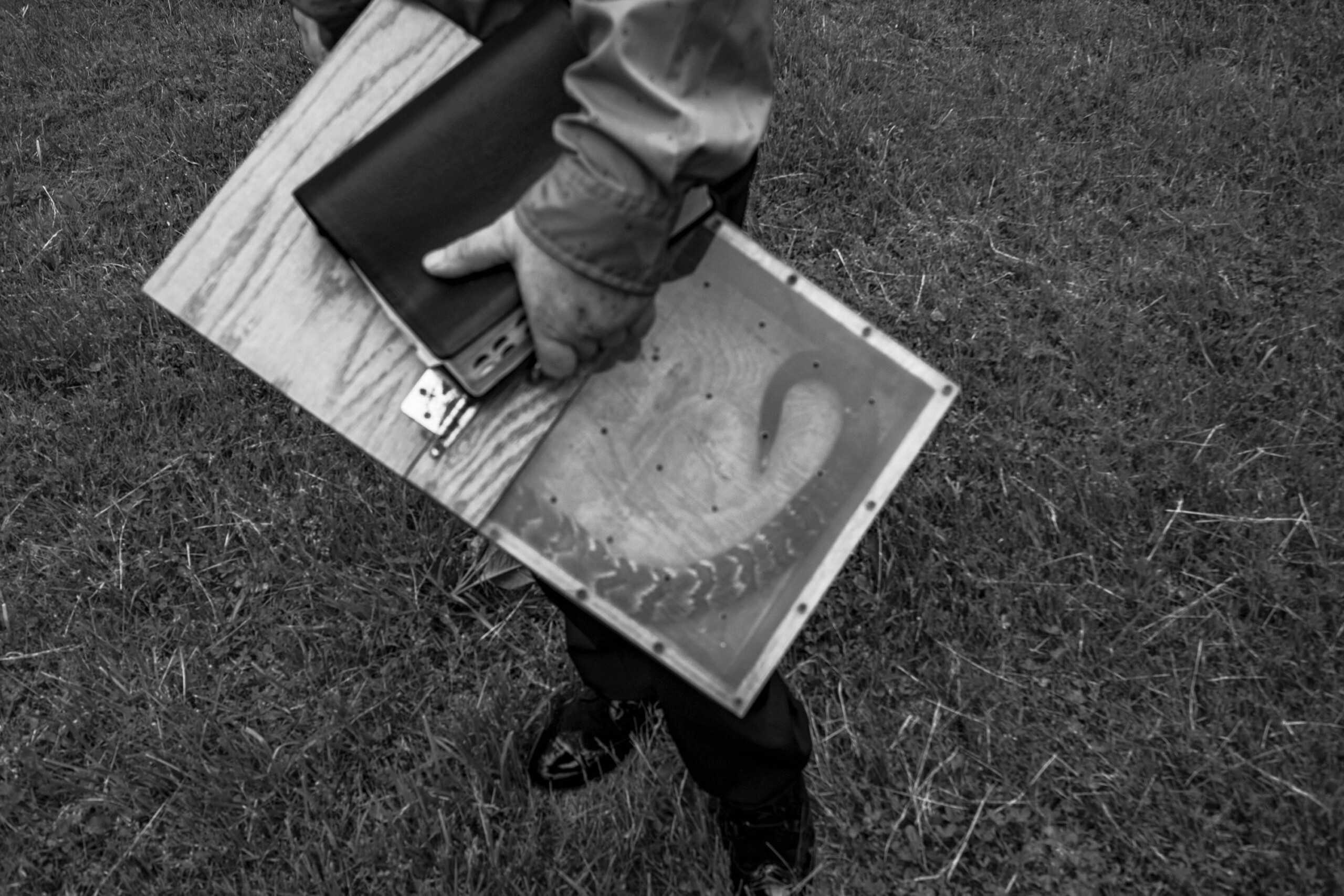

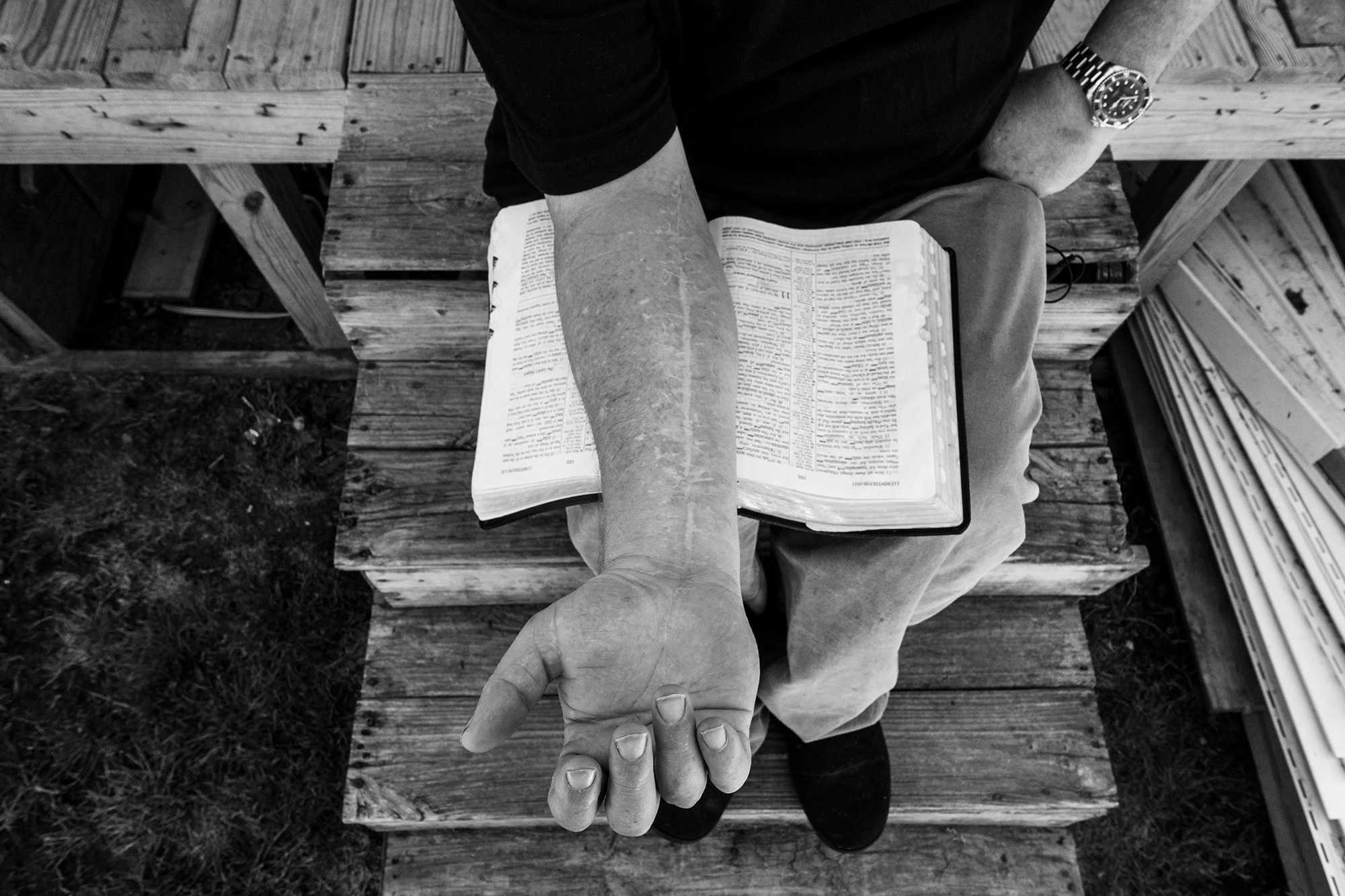

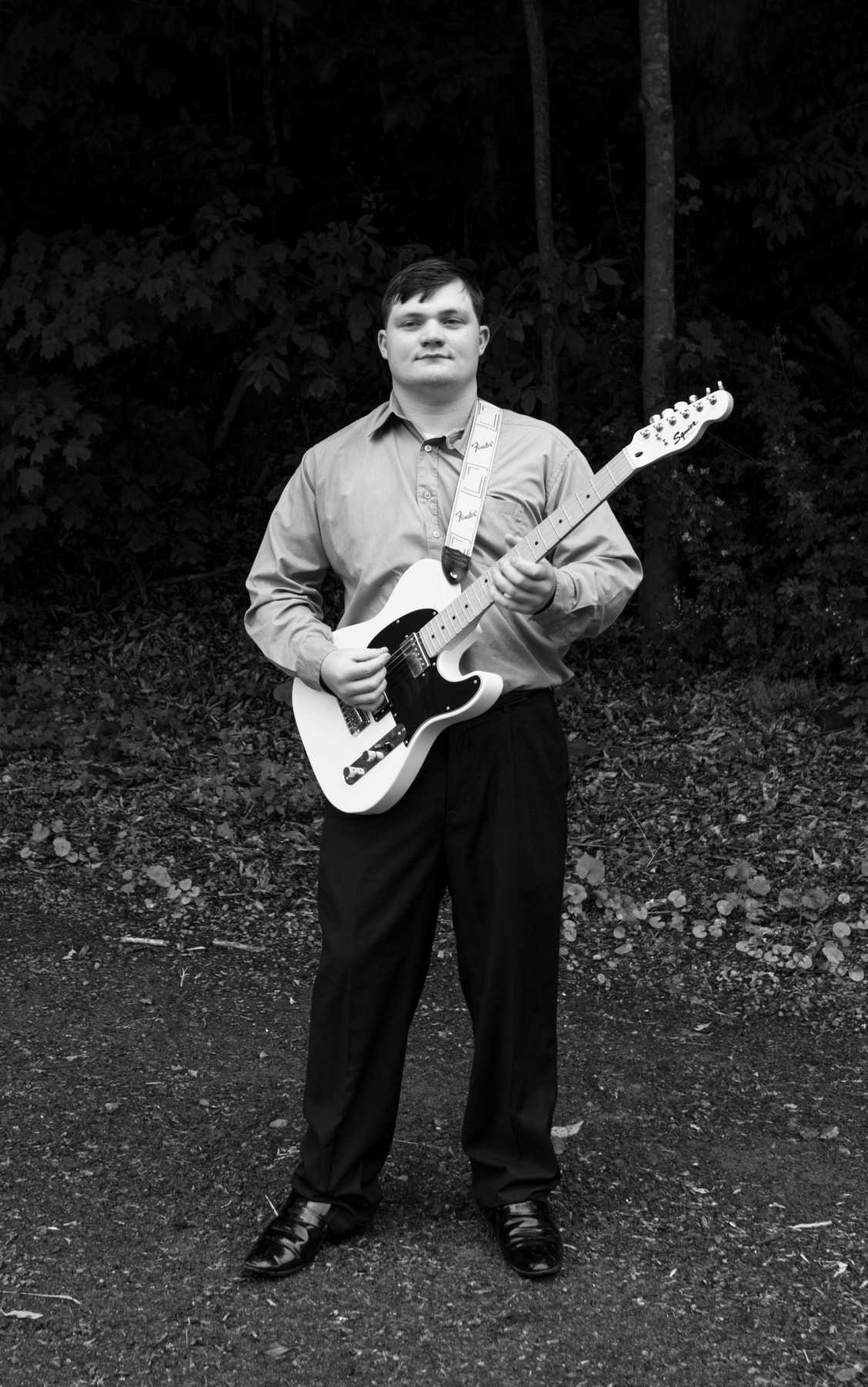

For his long-term project, LeBlanc spent his days studying these deadly practices that are on the verge of extinction, whilst building relationships and trust with his subjects. He was welcomed with open arms, which enabled him to photograph the community and their demonstration of devout faith to the King James Bible from a position of immediacy and closeness. This sense of mutual engagement and transparency is apparent in his series of raw, unguarded black and white images that traverse the worlds of documentary and surrealism.

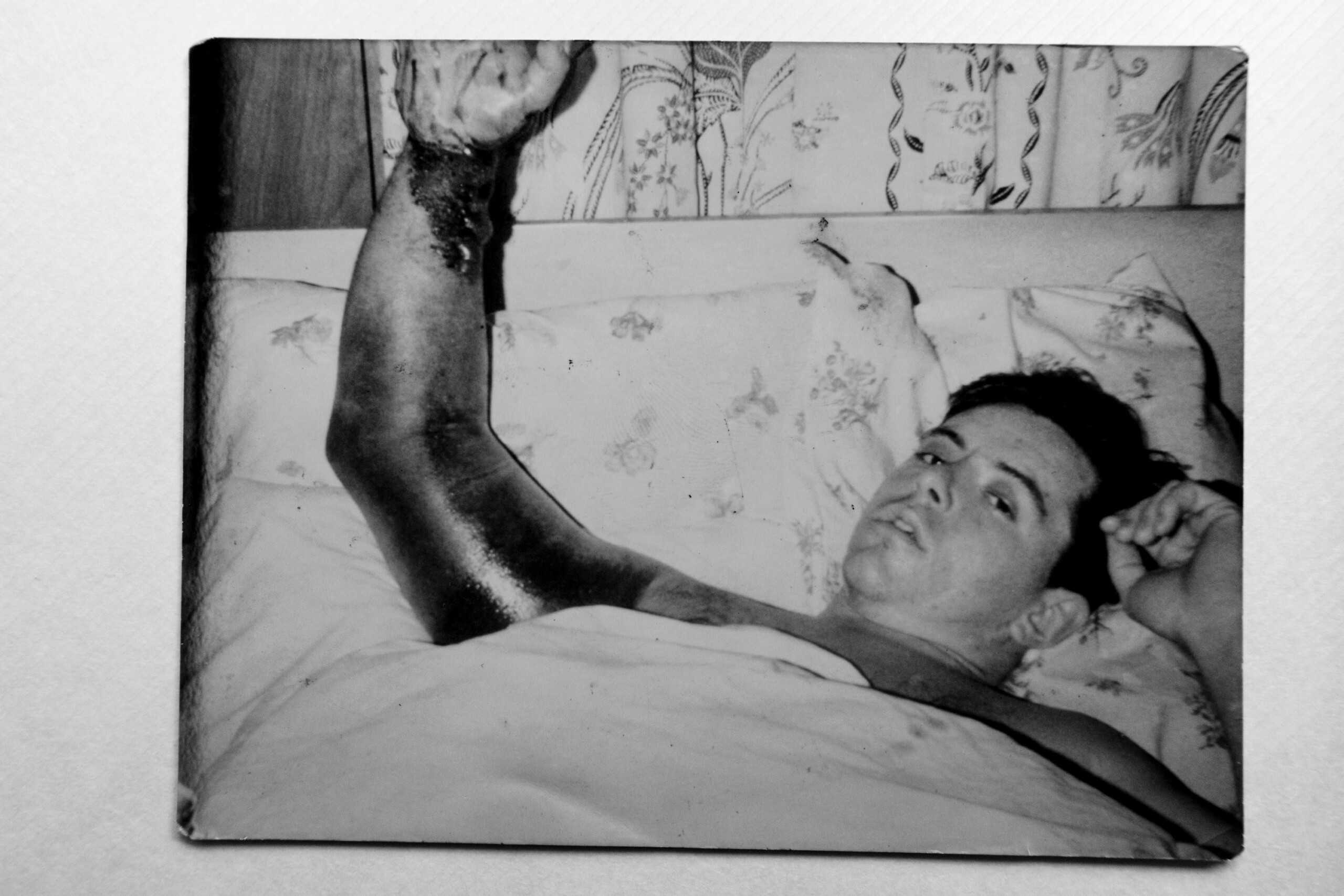

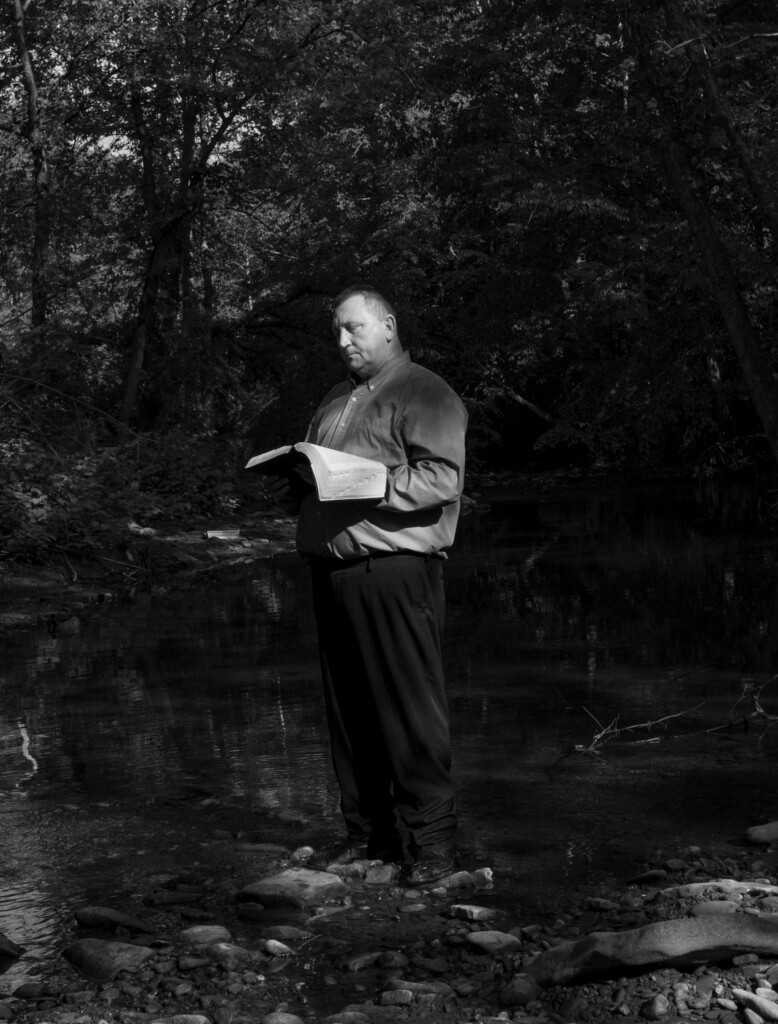

Church pews and old wooden panelled walls embellished with certificates, photographs of family members who died by rattlesnake bites, spiritual quotes and proverbs — a concoction of religious elements creates an interesting backdrop for the array of tableaux. Bluegrass music permeates the service as people dance, cry, sweat, scream, sing and pray. Glass bottles filled with alcohol are set alight and held under the chin. Flames rise up, like the snakes crawling their way out of their perspex confinement and onto arms and legs with scars and bite-marks proudly worn as a symbol of survival. Energy-loaded images are juxtaposed with tranquil still lives and portraits, including one of Pastor Chris, reading the bible outside in the forest, stood in a small creek.

In GLORYLAND, LeBlanc’s photographs are nearly as palpable as the act of serpent-handling itself.