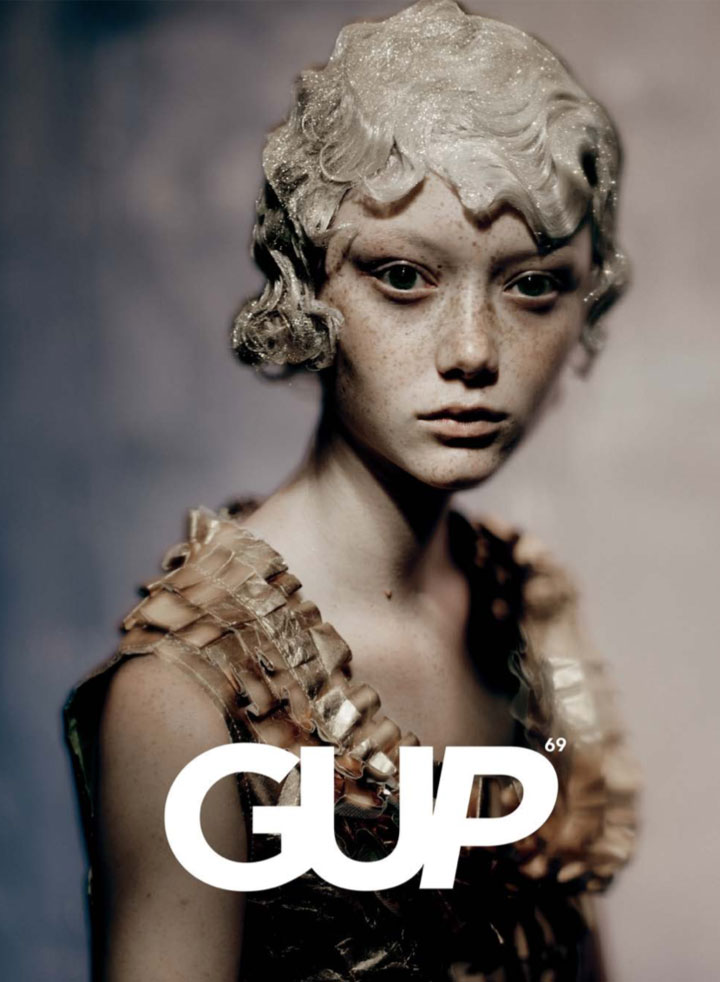

POST-APOCALYPTIC FAIRY TALES: AN INTERVIEW WITH ELIZABETH HAUST

CREDITS

GUP Author

ALEX BLANCO

Elizabeth Haust (b. 1992, Russia) has a background in photography, film and painting. Her work has been presented in museums, galleries and photo festivals all over the world including 5TH Moscow International Biennale for Young Art, GASK Gallery in Prague, The National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts, London National Portrait Gallery to name but a few.

The most recent appearance of her photographic work was in the Kiyosato Museum of Photographic Arts, Japan. One of the key programs of the museum is the Young Portfolio (YP), organised by the institution since its opening in the late 90s. The aim of the KMoPA is to support talented photographers from around the world under the age of 35, and six of Haust’s works have meanwhile been added to the museum’s remarkable photography collection.

For the occasion of being one of the selected photographers of this year’s edition of the KMoPA acquisition, we asked Elizabeth a few questions about her take on photography.

What is a recurring theme of your research?

I am a total romantic. I live in my own imaginary world spoon-fed with the story of my grandfather selling his blood to the hospital to buy a ring for my grandmother. I was always attracted to the idea of sacrifice and that’s what you see in my work. We live in a time when it’s complicated to open ourselves to someone without being judged. My work is the opposite, it shows vulnerability and emotional nakedness. It is there to be swallowed with skin and bones.

Apart from this, photography for me is a therapeutic medium. When I create something, I usually project my fears and frustrations onto the image, so these feelings stop being abstract and take the shape of a photograph. It’s like I am stepping outside myself and becoming a passive onlooker who is now envisioning the situation with confidence and courage.

Does your work, in that sense, appeal to the Japanese audience?

From what I see, Japanese culture might be slightly more reserved than the Western one, so people are drawn to art that pushes their buttons and allows them to express their emotions. My work is very open and honest, and it shakes people up.

How is that different from Russia, the country you were born?

I grew up in Moscow, and since I started photographing, my career took off quite well. My work speaks to Russian people for the same reason it might be interesting for the Japanese or any other audience – because of its ability to grasp feelings and reflect them back to the viewer.

I was always attracted to the idea of sacrifice and that’s what you see in my work.”

Is it easy to understand your work?

A lot of my photographic references come from deeply emotional and dramatic movies of the Russian filmmaker Andrey Tarkovsky (1932 – 1986). But even when not familiar with this reference most people can understand the atmosphere I try to imply, and this is what I cherish the most. Mood, feelings and atmosphere are the keywords that define my work. If you want to get the meaning of the photograph, then you need to connect to your own senses first. Another thing that facilitates understanding is the timelessness of my work. My photos might look like they have been taken a long time ago, but also, just yesterday.

Your photographs appear as very magical. Is there any deliberate connection to fairy tales?

I am most definitely a fan of the brothers Grimm and I am also inspired by old Russian fairy tales. I love the genre of post-apocalyptic fairy tales with dominant empty spaces and forlorn characters – something that you can encounter either in a dream or in a deep well of the subconscious.

What inspires you to create a new photographic project?

The main motivation for photographing, in general, is a feeling of excitement. When I hear the voice “woohoo” inside me, I know it’s a good sign and I am on the right path. The “woohoo” comes when I watch something, talk to people, read or listen to music. And to be honest, I am not really into making projects. Mostly, I take individual pictures that have a strong presence and manage to convey my idea. When I feel the idea has ripened inside my head, I start looking for a location and a model.

Generally, my subjects are women, as for me, a female figure is an example of tenderness but also strength and resilience. Women are connected to spirituality, old rituals, but also, they are mothers, they are the beginning of everything. If you think of a symbol of a Russian matriarchy – a matryoshka doll – it also represents a lot of what I want to tell: a story about a clan of women and a strong bond between them.

If you think of a symbol of a Russian matriarchy – a matryoshka doll – it also represents a lot of what I want to tell: a story about a clan of women and a strong bond between them.”

How do you cast your models?

I only work with people who share my ideas and with whom I have some sort of connection. It’s more complicated to cast models than it might seem. I look everywhere I can, in my social circles, on the street and even on Tinder (laughing).

What are your future aspirations?

I hope one day I have enough financial funds, so I can invest more in my photography and be able to create other, more ambitious projects. I also want to move onto producing movies and make something emotionally strong that can sweep one off their feet.

Any plans of making a photobook?

In the past, I used to create zines and I really enjoyed the process of choosing the binding, the right paper and the printing technique, all by myself. Maybe one day I can create an incognito zine and send it to people by post in a black folder with a strong smell of perfume. I like these kinds of initiatives: intriguing and fun.