Growing up in Detroit influenced the photography of Shawn Bush (the USA) and the way he thinks about social, economic, and political elements of the American landscape. As a lens-based artist, Bush responds to the urban environment which surrounds an individual and the meaning behind it. His work investigates the mythologies which are present in the contemporary and function as pillars of our societies.

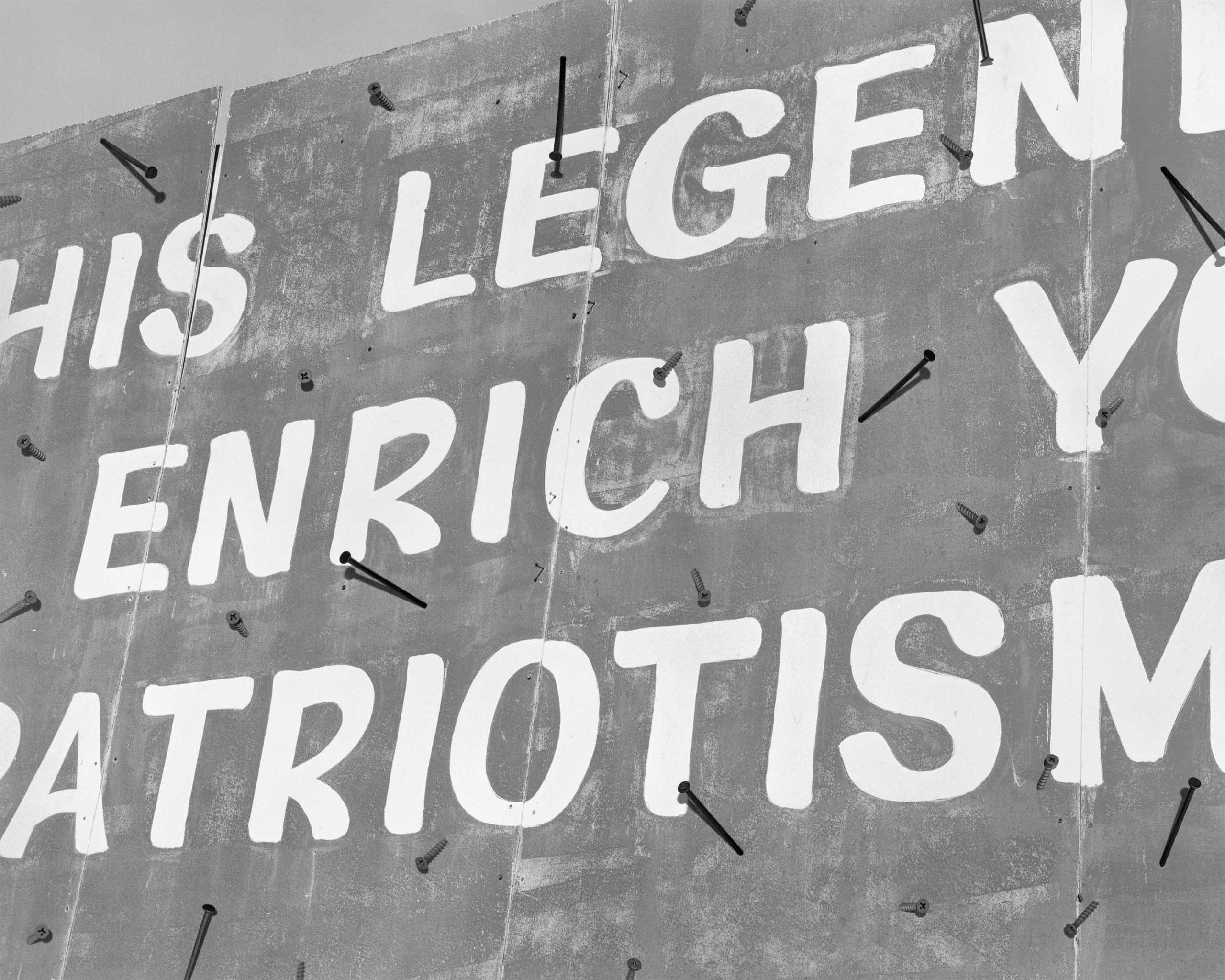

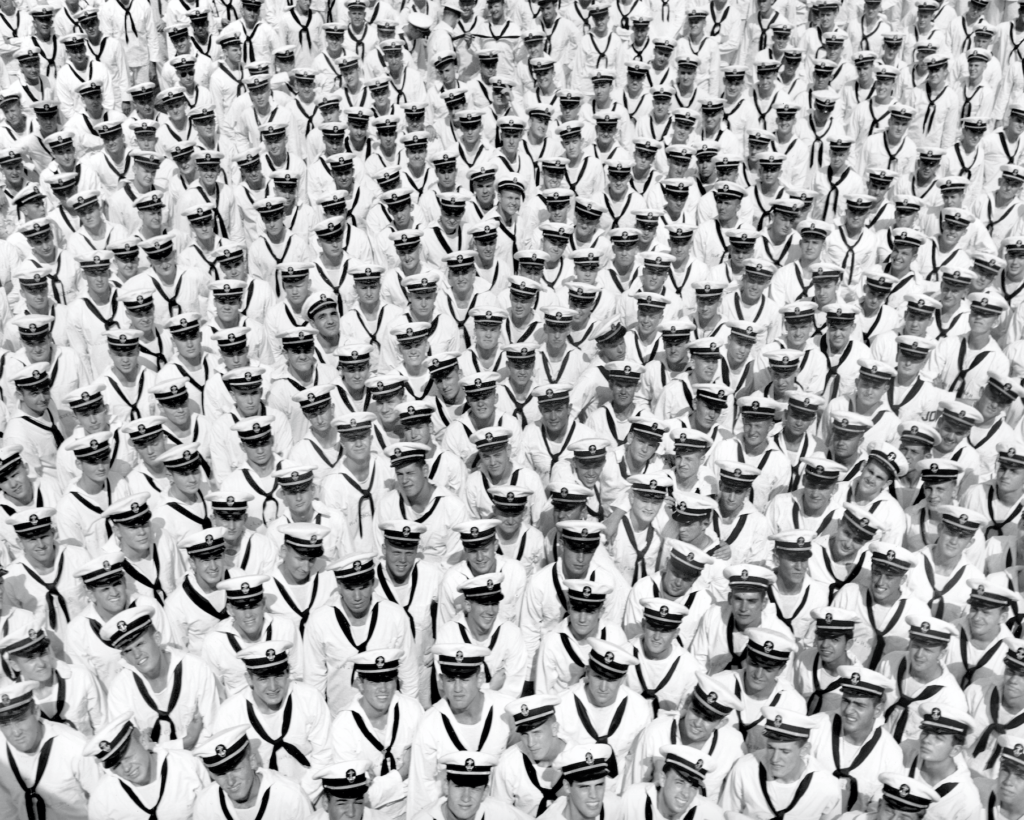

In his latest monograph, Between Gods and Animals (published by VOID), he investigates “the American straight white male’s endless pursuit to sustain power and the institutions that enforce their supremacy.” He combines both archive (featuring photographs from the 1920s up until the early 1970s) with newly created imagery. We, therefore, sat with Bush to get to know more about his intriguing project.

Your photography concentrates on the social, political, and economic landscape of the United States. How do you see your positionality as an artist amid the contemporary landscape of America?

My position as an artist is indicative of the photographs that I make, which focus on failing icons, crumbling mythologies, and overbuilt systems within Western (American) culture. This work, and all of my work, approach these spaces through a critical lens, which hopefully represents my position or beliefs within the context of socio-political and socio-economic landscapes.

Do you treat photography as a response, documentation, or rather something else to the socio-political landscape of the United States?

Because this work spans over twelve years of my own image production juxtaposed with archival photos, I see it as a response, documentation, and an assemblage of a shared history of colonialism and supremacy for the white (CIS) male society.

“All bodies represented in the book are directly involved or complacent in perpetuating traditions and myths of masculine power and do not focus on those who have been disproportionally oppressed by these systems.”

How do you visualize a topic which concerns diverse identities?

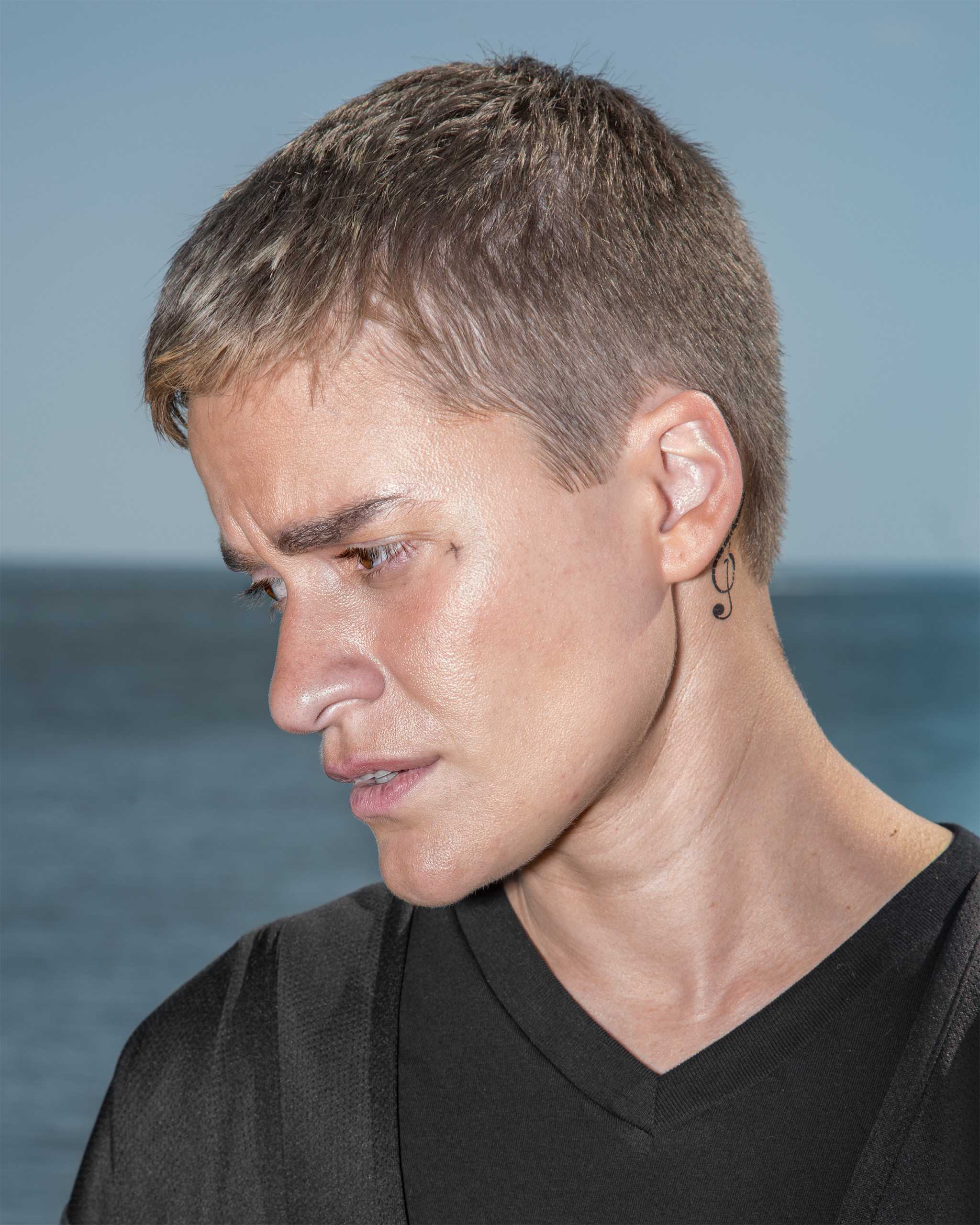

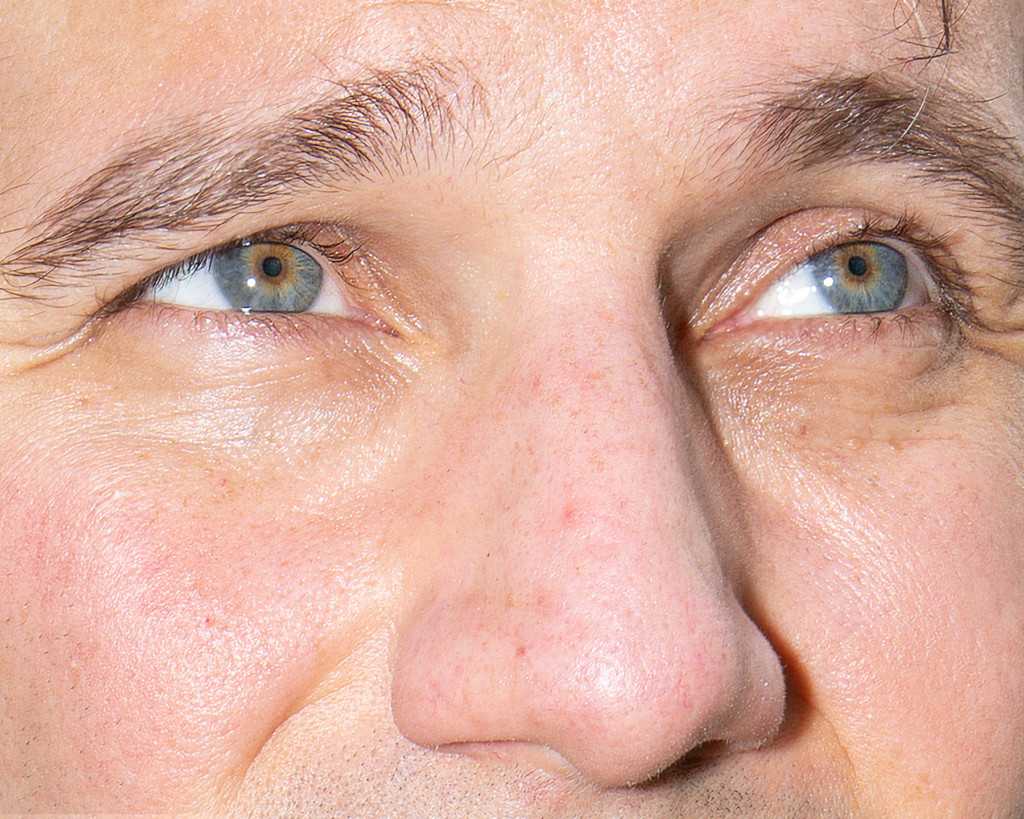

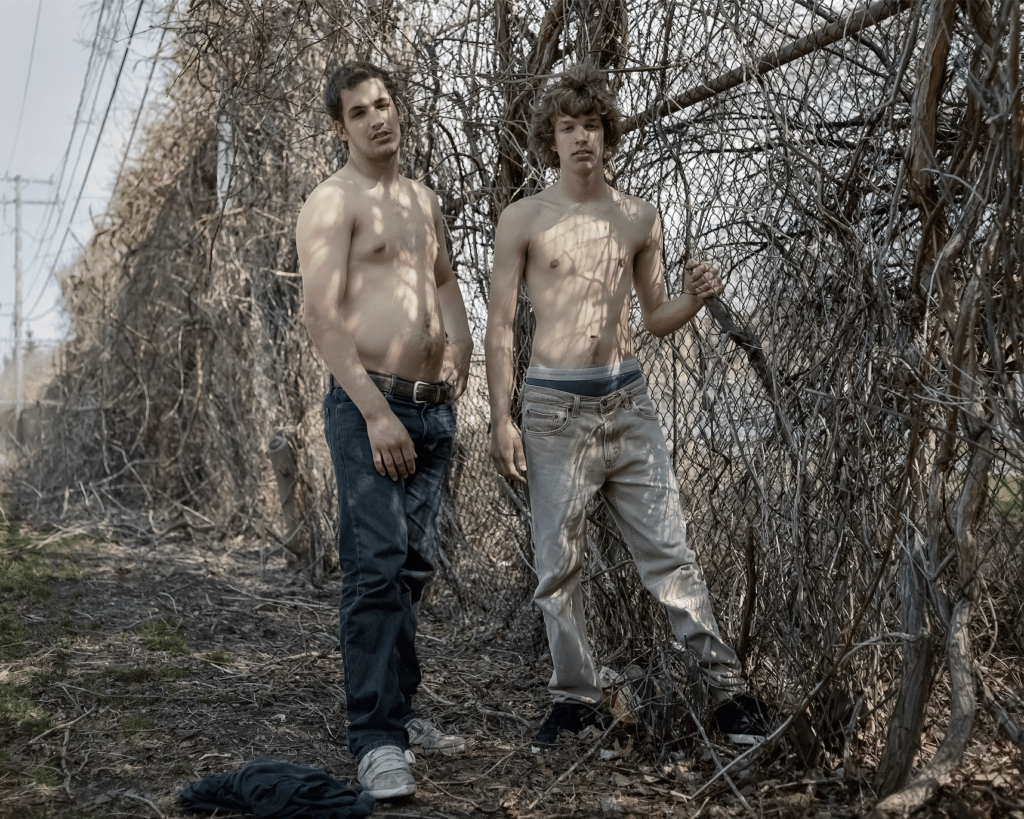

A few methods are used in this work to represent a diverse set of beings within the subsect of the straight white American male. First are my own portraits of men, all white and photographed in colour. I found it necessary to use colour images to visualize the nuance within the hue of Caucasian skin, which is often generalized as a single colour within colour photography and restricted to a small range of values within black and white photography. I also attempted to not only photograph one age group but instead, a variety of ages to suggest tradition and burden is passed down generationally. All bodies represented in the book are directly involved or complacent in perpetuating traditions and myths of masculine power and do not focus on those who have been disproportionally oppressed by these systems.

The narration of your photographs unfolds in the United States. Do you direct your photography only to American audiences or through your images do you want to refer to themes that are internationally universal?

I would like to think that the work could be internationally understood, though perhaps this is entirely false. The series is uniquely American but touches on themes of power, race, and privilege, which can be felt worldwide. What is seen and described in contemporary mass media about the white supremacist groups, the far right, and American maleness focuses on the extremes of those involved and their movements. However, most white men are not directly involved in these extremes but share a biography of entitlement and brutality, which is a burden for some and a badge of honour for others. In this book, I want to show that dichotomy and provide access to what the decline of the American patriarch and a loss of authority looks like for those who don’t have access to witness it unfold in person.

“The series is uniquely American but touches on themes of power, race, and privilege, which can be felt worldwide.”

In your photography do you perceive aesthetics to be an important component of politics or the other way around – politics as a valid part of aesthetics?

I certainly think that aesthetics is an essential component of politics, which was part of my impetus to include the propaganda archive – highlighting the contribution photography has in constructing the national imaginary surrounding social, economic, and political landscapes. I also used traditional genres of portraiture, landscape, and still life photography to suggest the omnipresence of white male privilege within Western culture, showcasing how it is executed within the body, within physical space, and within the capitalist goods that surround us.

In Angle of Draw, your latest project, you juxtapose 20th-century Western propaganda photographs with your contemporary work. There you examine the role white men had in their strive for control of different spheres of life. How is your photography representative of the voices not defining themselves as belonging to the white male social group?

The gaze of the photographs in the book, or rather most of them, is meant to represent vantage points of bodies that are not white and/or male, which I would describe as critical and focused, rather than an endearing and revered. The decisive moment when the shutter records highlights moments when the guise of masculinity has been dissolved in front of the camera. When the fear, anxiety, and weight of a prescribed performance begin to inform how the performance will manifest in the future. The curated gaze and decisive moment in the propaganda photographs reflect those in my own pictures. As the project evolved, I began to photograph using black and white film with a similar visual language as the archive to connect two distinct periods of liberation and fear within the American white male community as a device to confuse authorship, hopefully prompting viewers to question the intentions of established social, political and economic hierarchies formed by affluent white men.

“The decisive moment when the shutter records highlights moments when the guise of masculinity has been dissolved in front of the camera.”

Would you say that confrontation with the past is the only way to progress collectively as a society?

I don’t think that it is the only way to progress as a society and would like to believe that there are alternate avenues to reach an end goal in any situation or environment. However, I know there are limits to capacity. That being said, I find great importance in looking at the past to educate oneself and find those markers within contemporary society so that we are primed to identify issues and take action. It is difficult to act on what we are not exposed to.

As a photographer do you have a message which you want to put forward or do you want your photographs to speak for themselves?

Like many things, I don’t seat myself in either camp wholly. I hope and believe the photographs can speak for themselves and generally communicate intent to viewers. However, I don’t think that every picture speaks for itself without the context of those surrounding them and the materiality of the book space. This work shines within the book because it allows image, sequence, scale, text, and material to synthesize into something cohesive and connect the dots into a visible constellation. Viewing images outside of that space may make the concepts more obscured, though I think the pictures are direct enough that any viewer can conclude what the work is, or could be, about.

What are your predictions for the future about the medium of photography as a vehicle for social, environmental and political change?

There is abundant potential for photography to act as a catalyst for change. However, I think that there are limits to how that can manifest based on one’s practice and the venues in which images are disseminated. While I am not active on spaces like Instagram, Twitter, and TikTok, I think they provide a lot of room for artists to publish their ideas and works to a diverse and international audience at little or no cost to the viewer, which can be difficult when showing work within a gallery environment that is only being offered in a specific space. I look forward to seeing how future generations of artists exploit technologies to help form inclusive and just societies.

The Angle of Draw was published by VOID, you can purchase a copy here.