Brussels-based photographer Bertrand Cavalier (b. 1989, France) has been selected for .tiff 2018, the annual publication for Belgian photography talent by Fotomuseum Antwerp. GUP talked to Cavalier about his latest body of work Concrete Doesn’t Burn, a research project that explores the effects of war on people and architecture in European cities.

You travelled to mostly large European cities to document the effect of history on architecture and then of architecture on the people who live in these cities. How did this idea develop? How did concrete become symbolic?

The idea for this project comes from a series of reflections on war technologies and warfare. I was looking for ways to talk about armed conflict and their consequences by avoiding the delicate position of photographing situations that I can’t fully understand at an emotional or historical level. I was pushed to look at our recent history in relation to the urban landscape questioning its origins, the meaning behind its aesthetics and its effect on people.

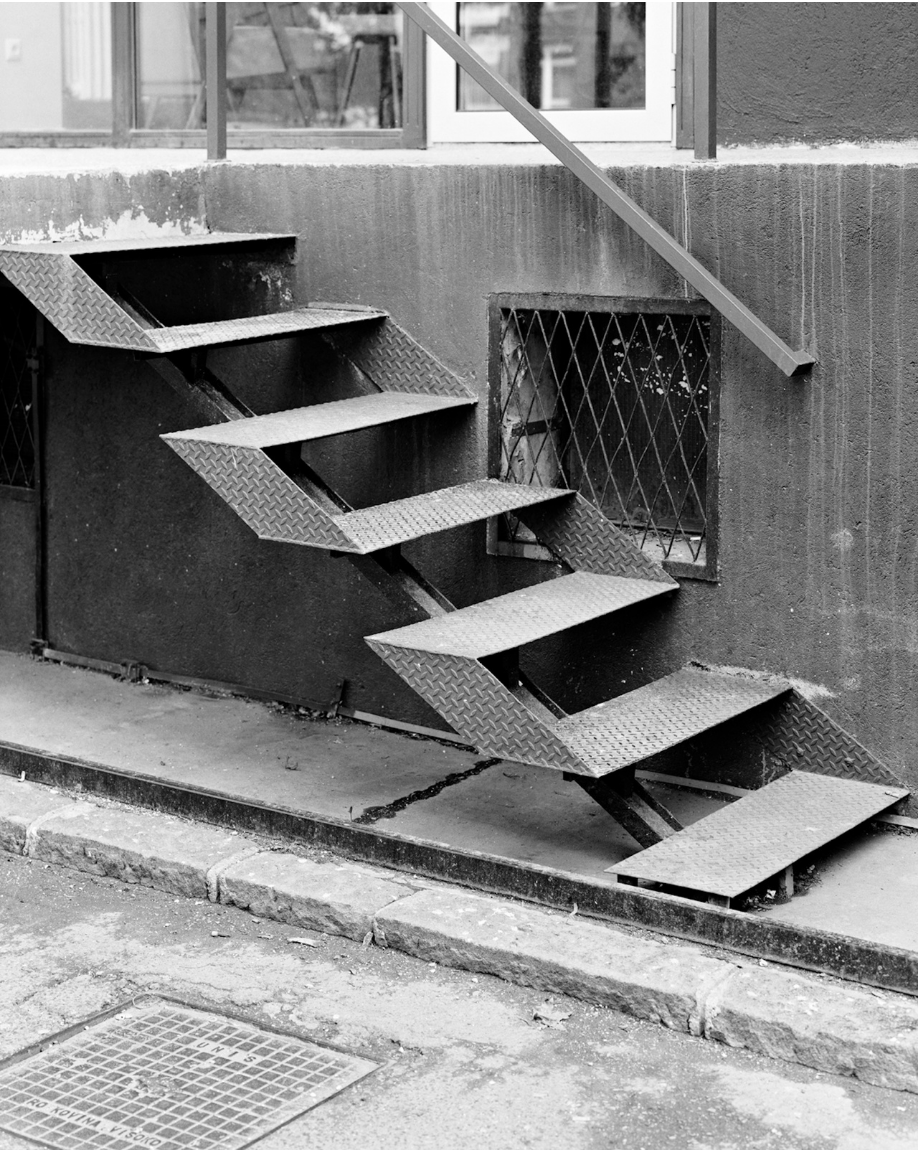

By using elements of the urban fabric such as concrete or steel, I tend to capture spaces that look familiar but are also charged with historical references. That way, I hope to influence the viewer to reflect on our current worldwide political situation and its possible consequences on the future.

You’ve photographed locations in both Eastern and Western Europe. How do these urban landscapes differ and what does it mean to put them side by side?

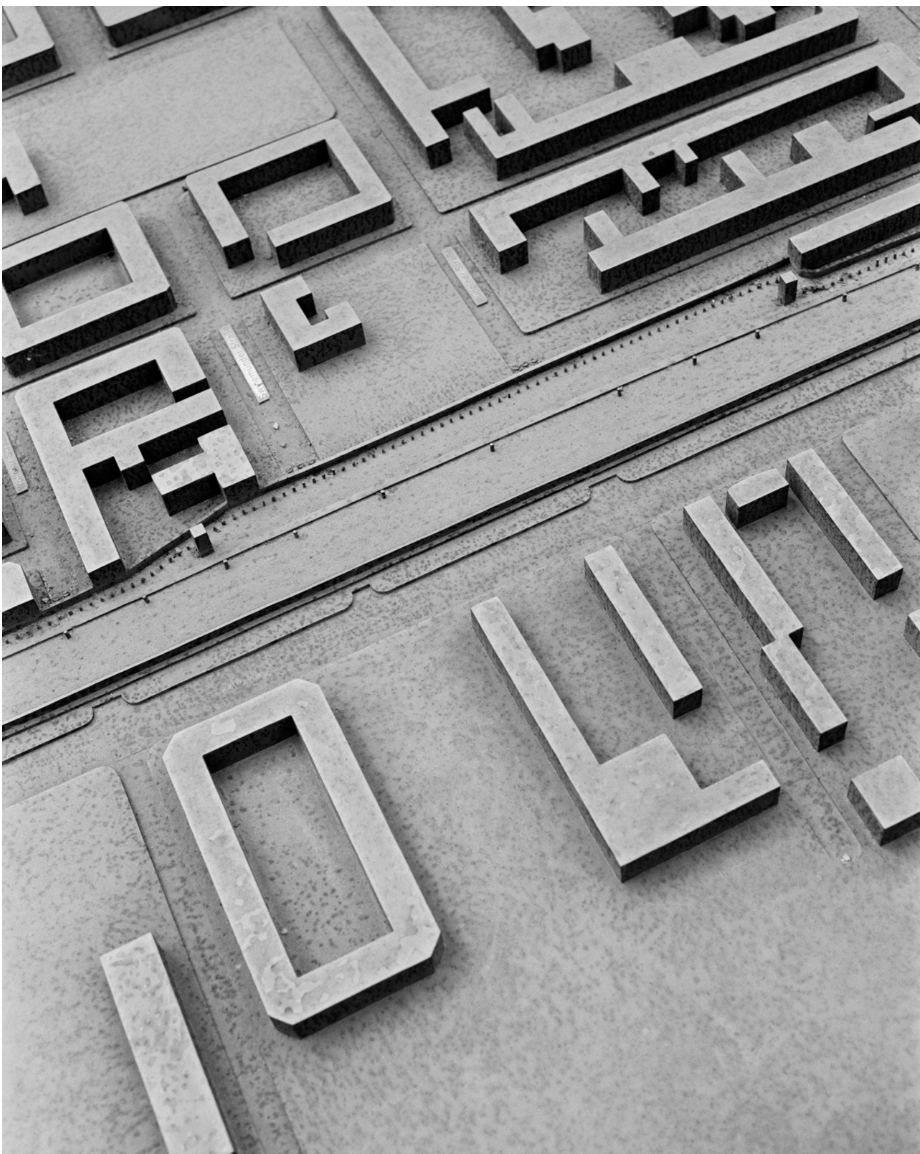

I’ve travelled to cities that have all been damaged by important conflicts such as Belfast, Sarajevo, Cologne, Le Havre, Warsaw, and many more. The sequencing of the photographs is made in order to emphasise the idea that the influence of a conflict on the space can be similar anywhere. The aim isn’t to be right or objective but to create a frame in which the spectator can relate to his own experience with cities and political issues. If the background of the work is based on a large documentation and specific facts from history, the photographs are made to be open-ended and to push the viewer’s self-interpretation.

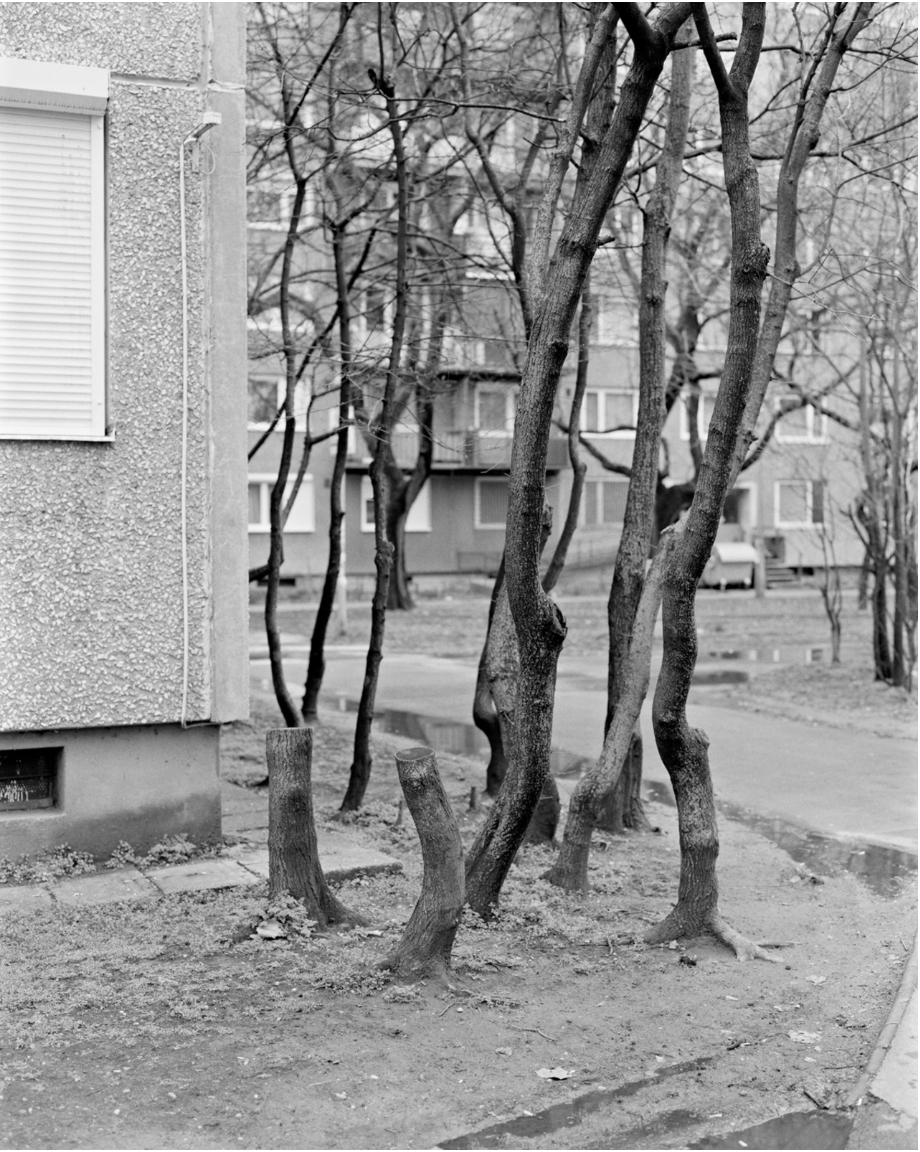

Concrete Doesn’t Burn shows city elements that appear to be hostile to humans. Straight angles, metal fences, cut trees and rough surfaces. At the same time, many of the cities you visited suffer gentrification, more and more people tend to move to these areas. Is there a contradiction? How do you see the “generation unaffected and young, yet burdened by the environment”?

I would say that some cities, like London and Berlin, suffer from gentrification. However, I think people are moving to gentrified areas because they’re looking for an interesting social dynamic. That being said, it takes time to change a city and the choices that were made during a conflict or a reconstruction. Let’s just have a look at the new use of the Flak tower in Hamburg, or the Tempelhof airport in Berlin which is now a public space. History will remain, even though people are making a different use of the space. Smaller and destitute cities still suffer from their past and I wonder for how long it can keep having a negative impact on people’s lives. In Belfast, fences and barbwire are visible on every house or neighbourhood, while in Sarajevo the cemeteries are everywhere, from the centre to the edges of the town. Anywhere we can observe young people growing within a space which has been defined by past conflicts.

In every city that I visited I could see the same model of constructing social housing. Through my research, I discovered that Le Corbusier’s influential building – La Cité Radieuse – was the first social housing building of this kind commissioned by the French government at the end of WWII. Nevertheless, in cities reduced to rubbles like Berlin, the social housing was built in the city centre and not out of it. I pay a lot of attention and importance to this detail as I believe it can generate social inequalities and a separation within the population.

Seasonal, your previous project, was focused on the interaction between people and nature, while Concrete Doesn’t Burn highlights the human reaction to urban environments. Also, you moved from colour to black and white. How did this shift come about and what should we expect from you next?

I think my artistic practice has always been driven by the political opinions that I stand for. Most of the time, a new project starts with personal readings on several subject matters. Lately, I’ve been interested in the dynamic of revolution and people’s emotion. In the future, I will keep exploring the relationship between the city and the citizen. Last summer, I started a new project in the city of New York.