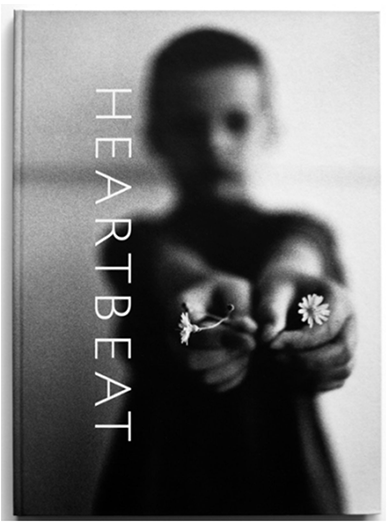

The picture on the cover is inviting. A boy offers the reader – or rather the viewer, since this is a photo book with only occasional pieces of writing – two flowers with outstretched arms. Two daisies, clearly visible because the photographer brings them into focus. ‘For you,’ the boy seems to be telling the viewer. Which isn’t true of course. He was only saying it to the person who took the picture, in the intimacy of that particular moment. But for the past thirteen years or so, the photographer has been able to lure all kinds of people, often strangers and unfamiliar people, into his books this way.

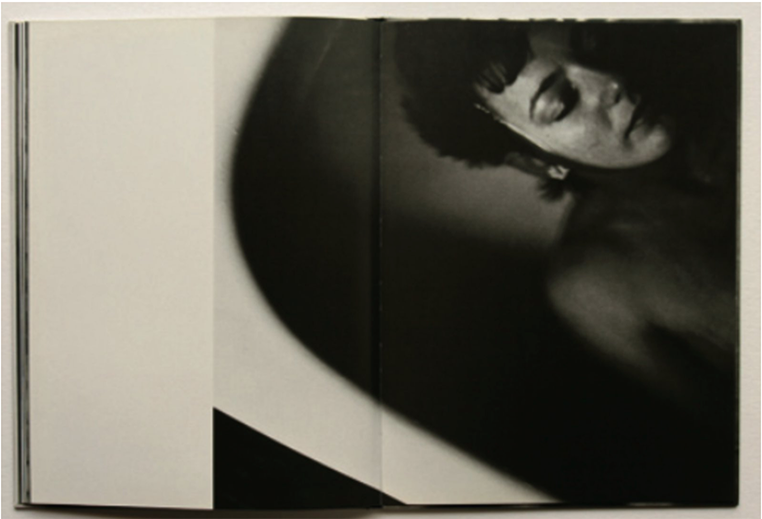

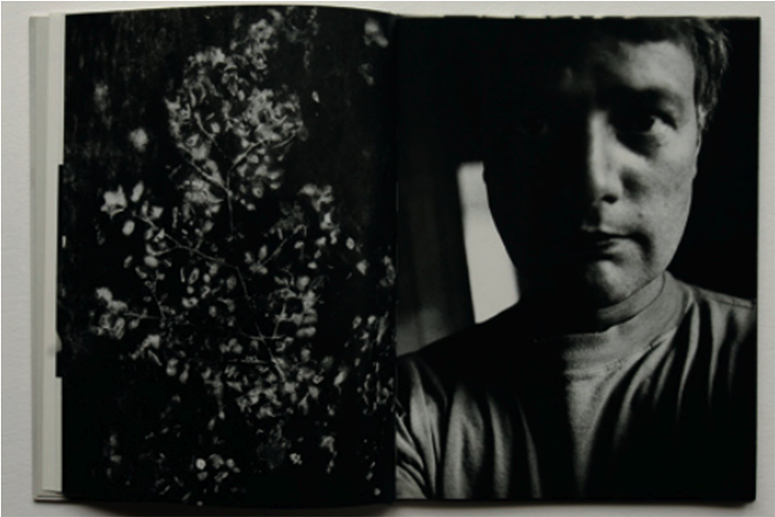

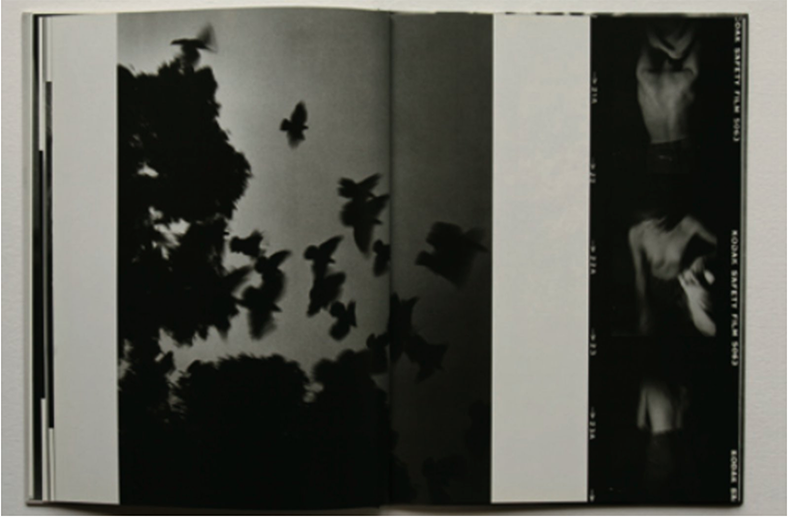

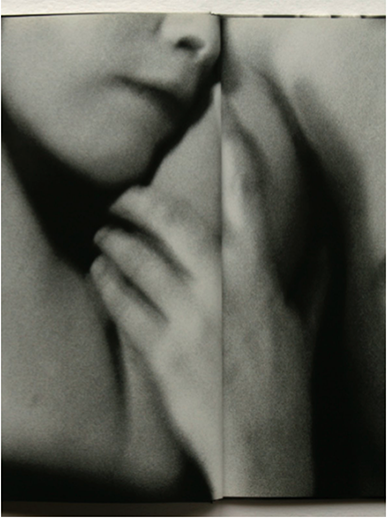

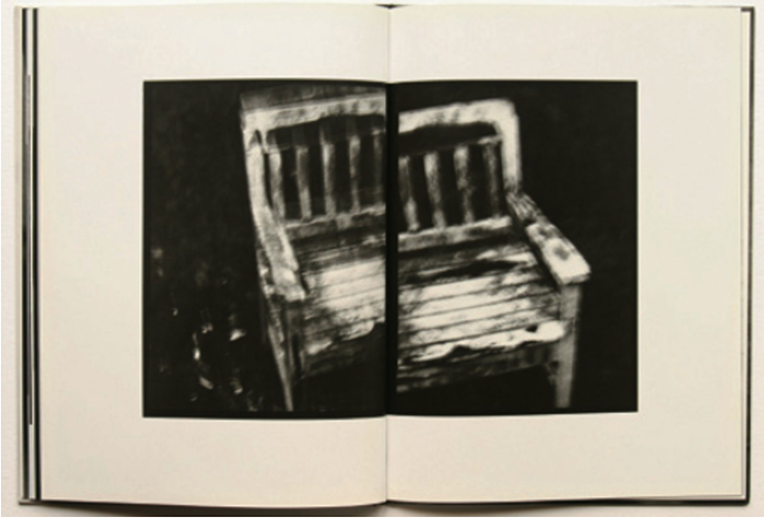

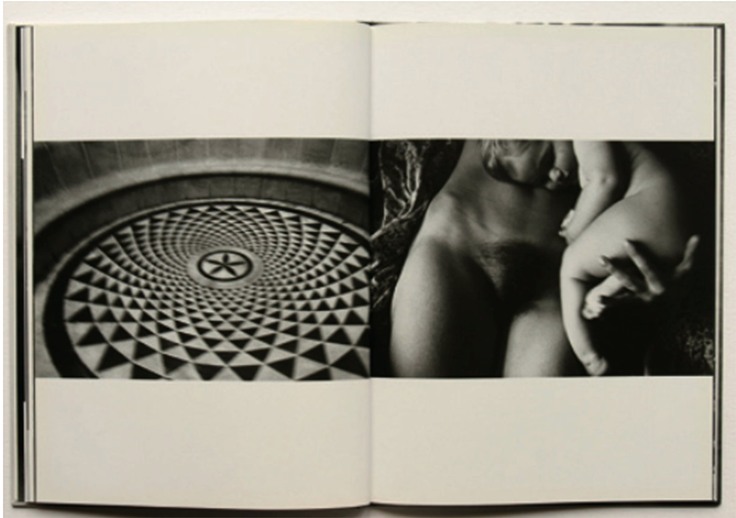

Heartbeat. A book by Machiel Botman (1955), photographer, teacher, curator and, in a distant past, a musician as well. Regardless of his profession, he became known for his love of the small, the tender, the intimate and the personal everyday moment, which is given universal meaning when it is captured and enlarged. The question of how the private can become public seems to filter through all of the photographer’s works. Although ‘question’ isn’t the right word, since it’s more of an observation. Machiel Botman makes no distinction between personal and professional work. His work is a record of his life, and always has been. Heartbeat (Volute, 1994) is a beautiful example of this. The austerity and the seemingly simple design of the book almost make you want to call it a graphic novel. It tells a story of love, death, illness, birth and eroticism, in the typical Machiel Botman style. The black-and-white photos are often blurred and stirring, sometimes appearing to show nothing more than a light spot, but the pictures contain a great deal more than first meets the eye. A woman presses something against her breast with a tender gesture. A baby’s head? If you look slightly lower, you will seethat it’s actually her lover’s upper arm. His body, her body (very likely the bodies of Machiel Botman and his loved one) – they become coarse-grained, almost abstract forms, images that are reduced to an essential contrast by the camera lens.

Universal images

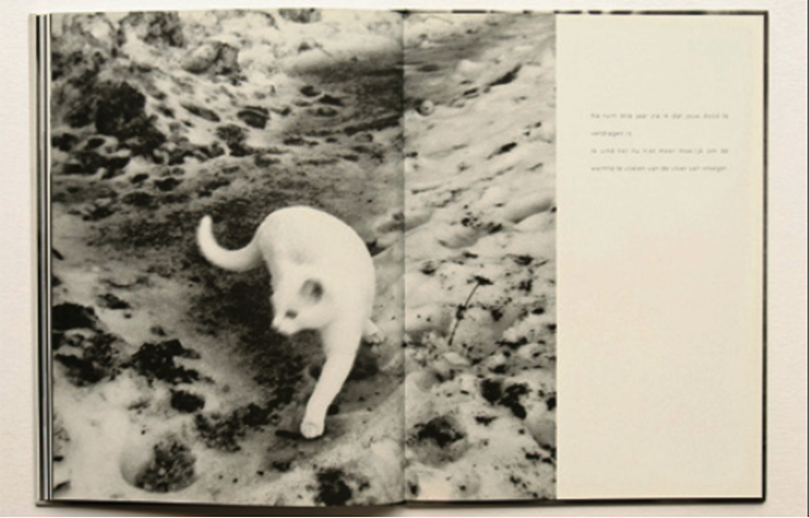

‘It’s a relief to be honest and not to have to hold anything back. It’s liberating to be in a position to look at everything. I feel completer as a photographer.’ These are Annie Leibovitz’ comments on her book A Photographer’s Life 1990-2005, in which the usually reticent photographer shows photos from her personal life, such as the birth of her first daughter. Leibovitz has always feared clichés. But in her case the opposite turned out to be true. Suddenly she recognized in her work ‘the essence of what drives us’. Heartbeat also contains these kinds of universal images. Machiel Botman also photographed his youngest son, sleeping on his mother’s naked body. However, he never turns the personal into something explicit. Heartbeat is about Botman’s love for his child (the boy with the daisies, who returns inside the book), his wife, his grandfather and his mother and about his older brother for who future changes will be possibly violent. That can be concluded from the short texts in the book, dreamy and associative thoughts, as if they trickled straight from the author’s head and onto the paper. But the book is also about love, about death in general and about the strange turns a person’s life can take.

Indictment of the ‘me’ culture

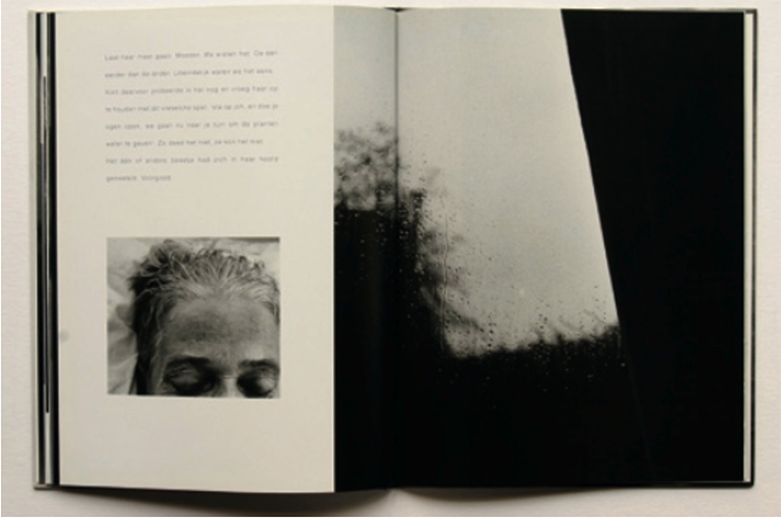

There are various portraits in the book, but only one of them is a self-portrait. And you can only figure that out if you know the photographer personally. Machiel Botman prefers not to explain. Perhaps the most explicit pages, which tell the story of his dying mother, appear right after the middle of the book. One of the few pinpoint-sharp pictures in Heartbeat shows the woman on her deathbed, but it is cut in such a way that only her forehead and closed eyes are visible. Next to her, rain runs down a window like tears.

Recognizable for everyone

The book still works, thirteen years after its publication. In fact it is not time bound at all, like other picture stories which are much more so, such as We are 17 (1955) by Johan van der Keuken. Heartbeat could have been published last year, a subtle indictment of this decade’s hysterical ‘me’ culture. With Heartbeat, Machiel Botman discovered a way of sharing the most intimate and emotional moments in his life with the world at large, without exposing himself or his loved ones. And, at the risk of using a truism, he found a way of making the personal universal and recognizable for everyone. In that sense, the book could not have been given a better title. It passes in a second, but if all goes well it will last a lifetime.