Linda Zhengová

Midnight La Frontera

Hardcover, 136 pages, 285 x 336 mm

$ 55/ € 49

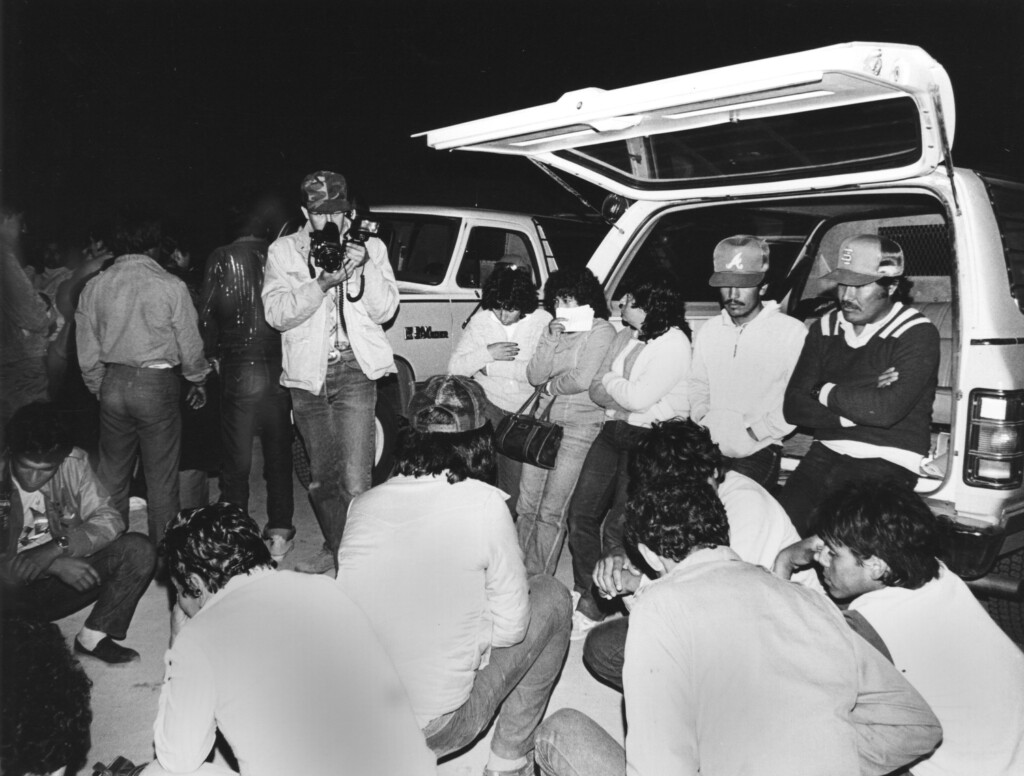

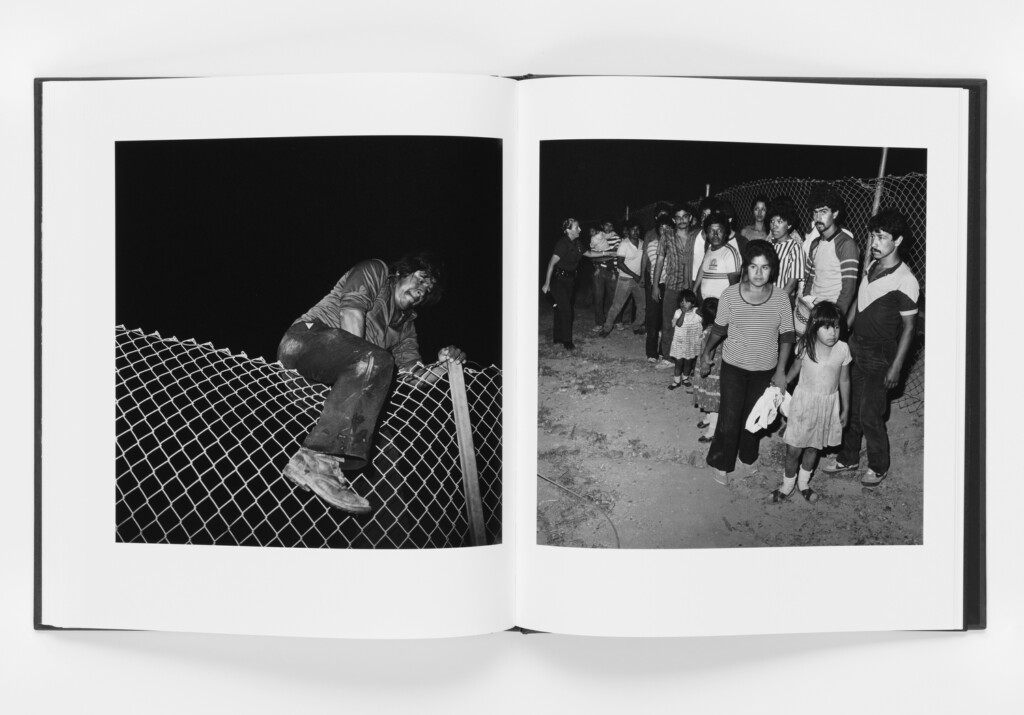

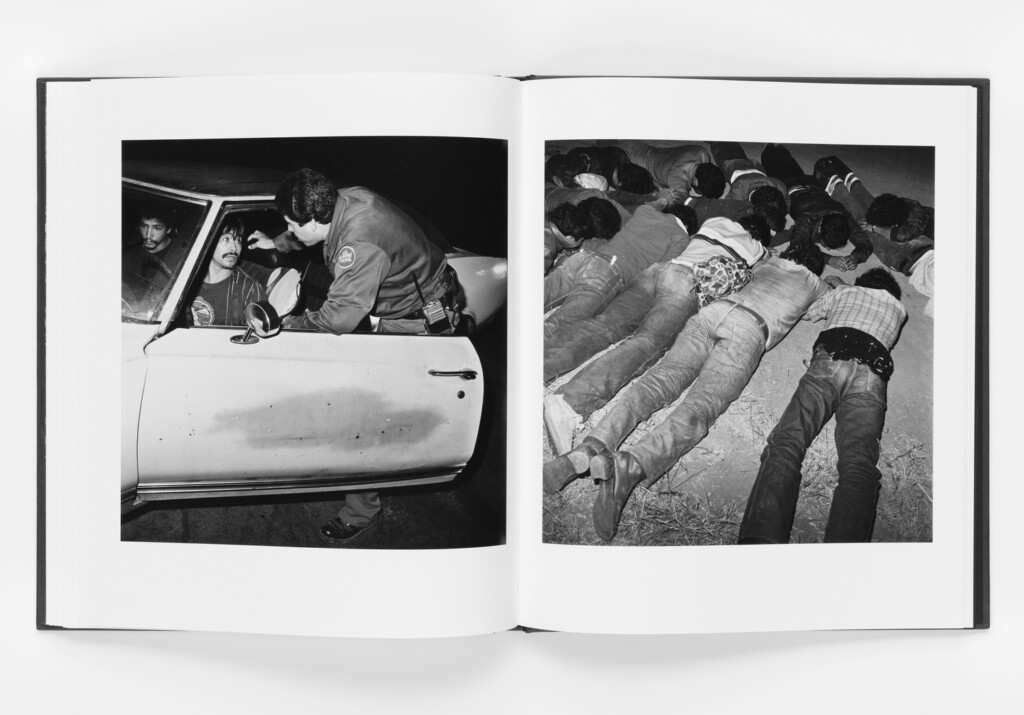

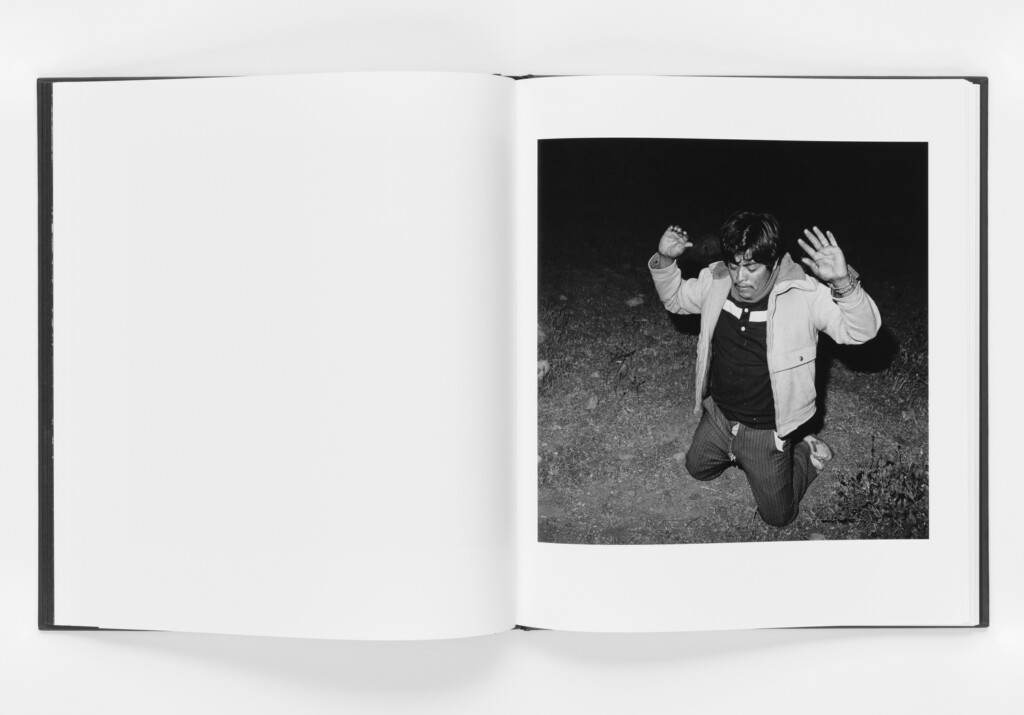

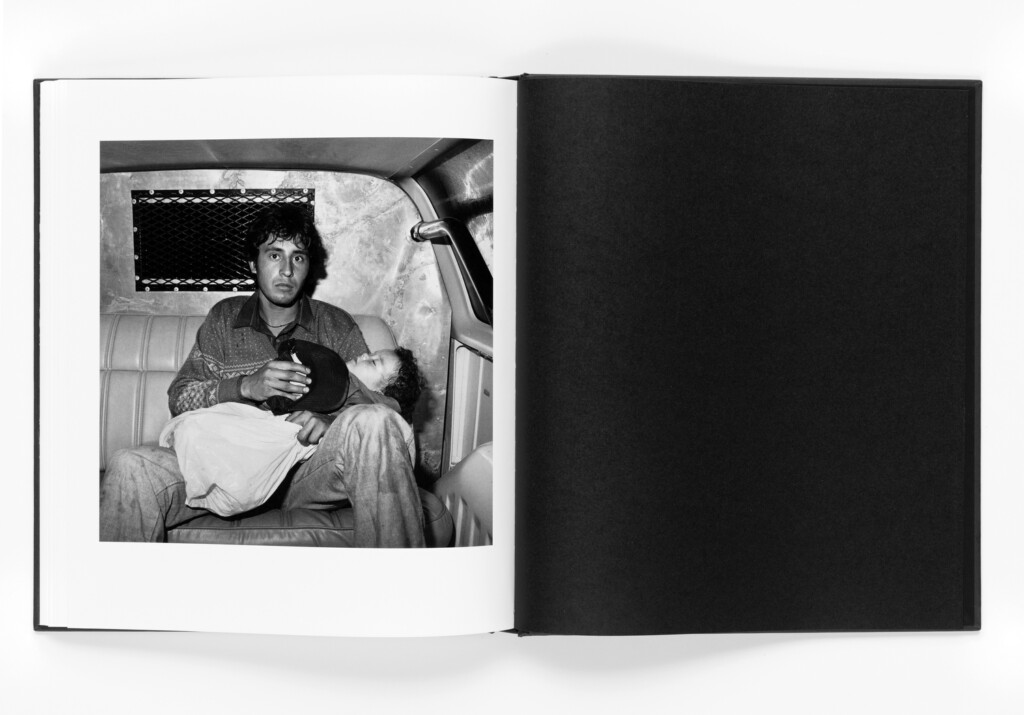

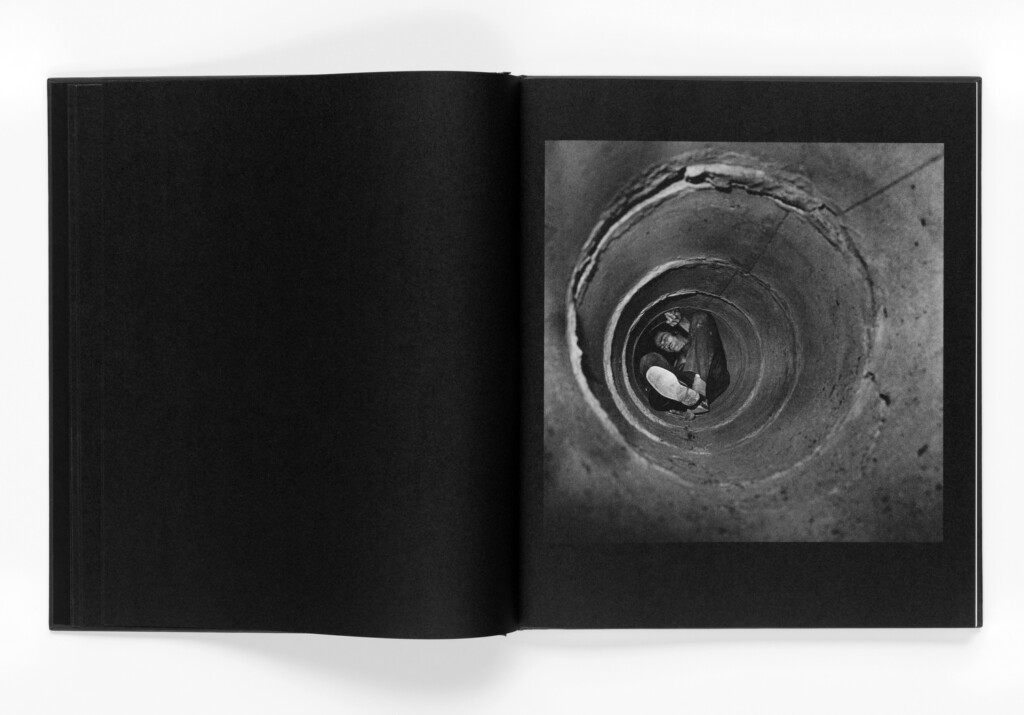

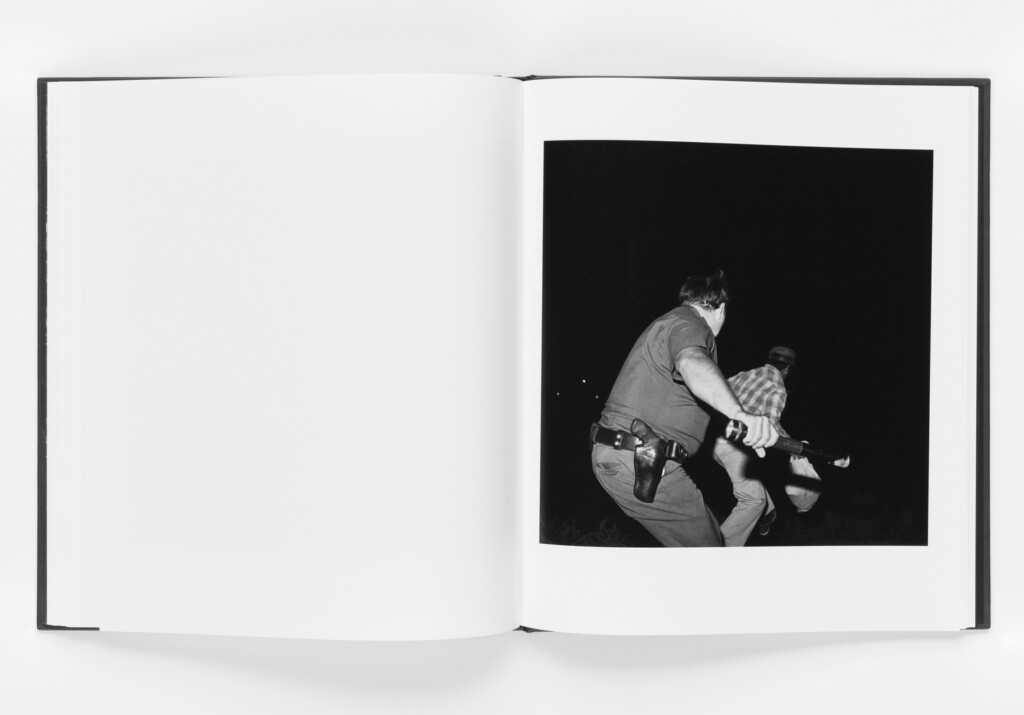

Ken Light (b. 1951, the USA), a renowned socially engaged photographer, re-visits his pictures taken between 1983 and 1987: night rides with the U.S. Border Patrol agents guarding the Californian/Mexican border. While the agents searched for migrants along the border, Light captured the moments when they were exposed. A state of vulnerability and desperation is caught in Light’s black and white nocturnal images that were shot on a Hasselblad camera with flash. These images are now published in Light’s monograph ‘Midnight La Frontera’ (published by TBW books).

In an interview with GUP, Light shares his perspectives on illegal immigration in the USA and the process of creating ‘Midnight La Frontera’.

When photographing ‘Midnight La Frontera’, you witnessed the first-hand reality of illegal immigration in the United States. How was that even possible?

When I did this project, I was lucky that the immigration people allowed me to be there with them – which is way more difficult to do today. Nowadays, you need to go out with the so-called PIOs (Public Information Officers) and they control what you get to see. So, they are not as willing to let photographers spend as much time nor to see the things that I saw. However, when I photographed in the 80s, they haven’t figured that out yet so then I just went with an agent who was working that night and I could just observe first-hand. In certain situations, in which we would be out at night, he would be hiding behind a bush waiting for the undocumented immigrants to come and I would be there right next to him.

How did it make you feel to photograph these vulnerable moments?

It was extremely hard and sad, but it was important to document. Also, I considered it from a personal perspective: My own family consisted of immigrants from Eastern Europe and immigrated in the 1880s and we have no visual record of their journey to the United States in steerage; there’s nothing.

When I took my first photographs at night, I realized that this was such a crucial moment to witness and record for future generations – for the children and adults whose grandparents or great-grandparents came illegally into the United States and have now become citizens. They will be wondering: what was my grandparents’ journey like? What happened? What did they wear? What was their experience?

Have you also considered following the migrants on their journey?

I thought about following migrants on their journey illegally but my main concern at that time was that I was using a Hasselblad, a medium format with film and a Vivitar 285 flash. We didn’t have digital cameras yet so that I couldn’t set the ISO at 12,000 when photographing at night. Since there was absolutely no light, I had to use flash.

I really felt that I would be compromising these people’s journeys. What they were doing was serious, it was about the reality of their lives and the desperation to find a new one in order to make money for their families. So, I felt uncomfortable with the idea of doing that. I’m sure I could have done it but using a flash at night would expose the people to the Border Patrol agents which would lead to their apprehension. That just didn’t feel the right thing to do.

Were you later informed what were the fates of some of the people captured on your photographs?

I saw them for the first and last time. I wasn’t able to get the names of people as I was photographing them. So, the answer is no, I haven’t connected with any of the people that I photographed. I hope to! It would be amazing to find out where they went, what happened to them. Have they ended up in the United States? Are they citizens? Are they still undocumented? Did they decide they didn’t like America and went back to Mexico? Did they not make it and they just gave up and stayed in Mexico? There are many questions that I have about their experiences.

“I saw them for the first and last time.”

“There are many questions that I have about their experiences.”

What made you decide to re-visit the images after more than thirty years and make them into a photobook?

The idea of America has always been that it is an immigrant country, and immigrants have really fuelled the scientific discovery, the art, the industry and the finances. When Donald Trump was running for election, he viciously created narratives that immigrants are rapists, or they don’t work, etc. This helped me understand that Trump’s attack was part of his strategy to make Americans fear that their country is being overrun. He omitted all the success stories of immigrants, including his own wife [Melania, ed.]! She didn’t come through the fence, but she came in and some even say that she entered the country illegally [from Slovenia, ed.].

That context made me come back to the work I did in the eighties. Some of it was published by Aperture in a book called ‘To the Promised Land’ (1988) but very little of this night work was ever published. I went back to my archive and pulled out my negatives and I was amazed that all these photos haven’t even been printed in the darkroom! And I just thought wow, this is very much different from how I was seeing or editing at that time. And now, the photographs resonate in a vastly different way.

“The idea of America has always been that it is an immigrant country (…)”

“(…) now, the photographs resonate in a vastly different way.”

How would you reflect on your collaboration with TBW Books when creating ‘Midnight La Frontera’?

I have done ten photobooks throughout my career. I published with many different publishers such as Aperture, The Smithsonian, University of California Press, University of Mississippi and Heyday. I would say that working with TBW – with Paul Schiek and Lester Rosso – was one of my best collaborations. It was really a collaboration.

As so often with books, the art director would take the work, shape it and decide everything along the way – the type, size, design and style of the book. Those are things that a publisher will choose for you and you can try to push back but they often see it as their book, and you are just the provider of the content. TBW was the opposite, they were completely open to collaboration. We had many meetings, we were looking and sequencing the work together. They kept coming up with ideas to the day we sent the file to be printed which was great.

So how does this close collaboration resonate in the book?

There are wonderful little things in the book. For example, the fact that we used black thread to sew the book rather than a white thread in order to denote the idea of a border going through the gutter of the book. The idea of using the mat black paper in the beginning and then changing to the glossy white paper was a great transition which creates full darkness, leading into the photographs in the second part of the book. The transition image, which is the double page of the man running, that was literally a last-minute decision and it just works so powerfully in how the reader looks through the book and sees the images.

The more we thought about not having the title of the book on the front cover, the more I realized that it works great as you are first confronted with an image of the woman and a child and then the title is just at the spine. For photographers, this is such a big issue and some photographers have their names so large on the cover which obliterates the image. I wanted the book to be about the people and their journey, not me. The way they designed the text is so powerful. The English is on the left and Spanish on the right, again gives you this idea of a border in the book. All these little things that we came up with collaboratively was a wonderful experience. We wanted to create an object; a book that would pay respect to the journey pictured in the photographs.

“We wanted to create an object; a book that would pay respect to the journey pictured in the photographs.”

In addition to images, the publication includes an introductory text by José Ángel Navegas, the author of ‘Illegal: Reflections of an Undocumented Immigrant’ (2016). Navegas provides his first-hand account of border crossing in his search for a better life.

Oh yes! I think it is one of the most powerful first-hand experiences of an immigrant on this journey. Often when reporting this story, it has been a white male journalist who has gone with immigrant groups and written about it. It’s very different in this book with Jose’s text as he is writing about his own journey as an undocumented person. Coming from Guadalajara, Mexico, he reflects on his experience of apprehension and how he ended up here in the United States when he tried the second time. He just received his Ph.D. at the University of Chicago, yet, even now, he is still undocumented.

Would you say that the book form is key for bringing the message of your projects across?

For me, the process of creating a long-term project and then putting it together in a book makes the whole body of work available for the viewer to look at. The problem with an exhibition is that it goes up for one or two months and then it comes down. Often people say, “I was planning to go to see the show next week, but it disappeared.” So, there is often no record and they are usually not showing the whole body of work that you’ve created as a photographer.

When I put the work together, it ended up being 86 pictures in total of which 66 are included in the book. Clément Cheroux, the senior curator of photography at SFMOMA, bought all 86 pictures for their museum collection. It was exciting to have that body of work not only in the form of a book but additionally in an institution – which is very important.

A show is really wonderful, but the book is always there. It’s in people’s libraries, museums, collections, in schools and it can, therefore, be seen and shared. That to me is part of the process of witnessing and creating. Long after I’ll leave the planet, the books will be there for people to see and that is something very meaningful to me.

“A show is really wonderful, but the book is always there.”

To conclude: What does socially engaged photography mean to you and do you feel you can facilitate a positive change in society as a photographer?

As someone who was a socially engaged activist [in the late 1960s, ed.], I realized my role as a photographer could be to document my own country, looking at the issues that are often ignored or unseen. I consider my work as being socially engaged by witnessing the stories that I am trying to tell and being involved in the conversation around these issues, sometimes even illuminating them when they are ignored.

Perhaps it is also inspiring for other photographers to document what I did so long ago now. There is a continuum that is essential in social photography. Every generation needs to re-witness the issues that continue, and immigration is, of course, one of the issues that has been happening all over the world ever since people walked on this planet, faced inequalities, political unrest, war, climate change and they needed to escape danger and build a better life, and probably will never end.

“I consider my work as being socially engaged by witnessing the stories that I am trying to tell and being involved in the conversation around these issues, sometimes even illuminating them when they are ignored.”

10% of proceeds from the book sales go to Al Otro Lado, a bi-national, direct legal services organization serving indigent deportees, migrants, and refugees, that is deeply engaged in efforts to protect the familial rights of migrants.