Triggered by the strangely Orwellian phrase ‘alternative facts’— a flagrant redefining of demonstrable falsehoods as truth by authority figures, introduced in the early days of the Trump administration — photographer Philippe Braquenier (b. 1985, Belgium) immersed himself in a community espousing ideas in the vein of this new mode of ‘alternative truth’: the Flat Earth society.

Of all of the paranoid speculation out there being disseminated, the modern flat earth conspiracy is perhaps the most ‘stable’ rumour circulating, tracing its lineage back to the 1850s with the release of English writer Samuel Rowbotham’s book Earth Not A Globe. Ever since, the flat earth community has seen a growing number of proponents, as well as a growing amount of exposure.

Rather than position himself as an outsider, Braquenier grants viewers a rather different look into the heart of the flat earth community and its many believers. His project Earth Not A Globe, which has been 5 years in the making, is an intriguing body of work that examines mankind’s complex and often dubious relationship with the photographic image in a post-truth era, where misinformation abounds and conspiracy theories have only continued to gain momentum.

On the occasion of Braquenier’s recently concluded exhibition “Earth Not A Globe” at the Ravestijn Gallery in Amsterdam (23 January – 24 April), GUP was fortunate enough to discover more about the process behind this fascinating project from the artist himself.

There have been many outlets exploring the flat earth community, yet none have taken the route you have: occupying the standpoint of the flat-earthers themselves and utilizing the very same tactics to make for an argument. What prompted you to take this “alternative” stance in your project?

Firstly with my preliminary research, it was interesting to see that the flat-earthers were mostly mocked. In the 21st century, it certainly seems crazy to think that the earth could be flat. After all, over 2500 years of accumulated scientific knowledge is being rejected with this statement. The aim of this project was not to talk about them alone, but mainly concerned with conspiracy theories in the broadest sense and on the cognitive biases associated with them. I therefore chose to get as close as possible to their points of view, which made even more sense given their use of empirical methods. By virtually integrating myself into their community, I noticed above all that they were people who were plagued by doubt and who had a total lack of trust in higher institutions. I also wanted to use this doubt, as well as my authority as a photographer, to evolve in this grey area between fiction and documentary.

“… I noticed above all, that they were people who were plagued by doubt and who had a total lack of trust in higher institutions.”

The beginning of modern Flat Earth conspiracies, with Samuel Rowbotham’s ‘Earth Not A Globe’, coincides with the 19th century popularization of photography, and flat-earthers have consistently used the medium as a means to substantiate their beliefs – until this very day. What kinds of ‘techniques’ applied by Flat Earthers did you appropriate yourself?

Indeed! I had a similar thought, be it that Rowbotham never used photography in his observations. He only used a ‘longview’ device and then made simplified sketches to explain his experiments.

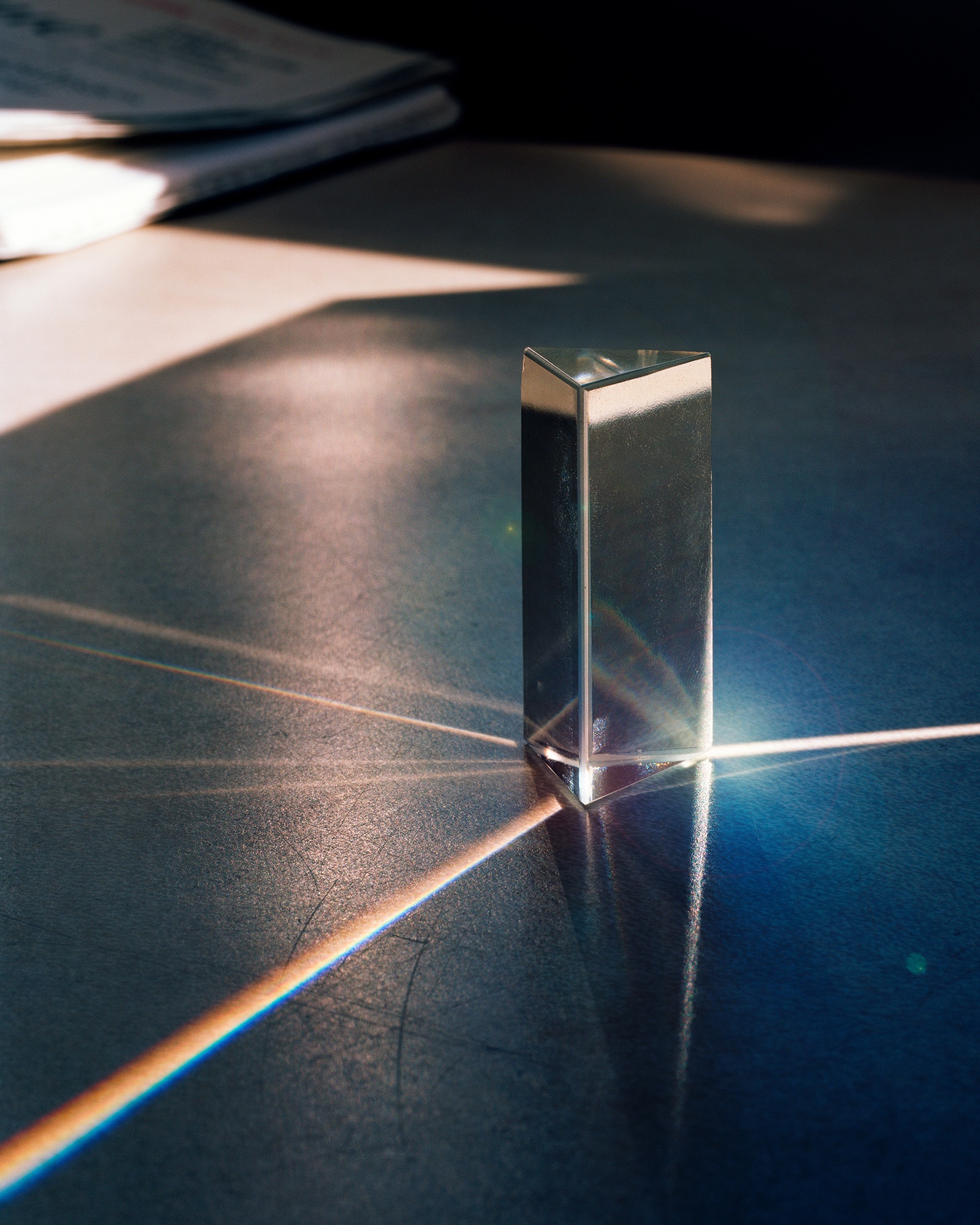

I have borrowed two techniques widely used by modern flat-earthers. The first is the application of explanatory drawings that they affix to the images to advance their theories, mainly in a didactic and direct assimilation spirit. I use the glass, which protects the photographic prints, as a layer. The patterns are sandblasted into it and then mounted in the frame in front of the image, acting as an additional information layer. But what I also like is that they interfere in some way with the reading of the image.

The second technique I borrowed from them is an amateur camera with a powerful zoom. They use it constantly for their observations. They film and photograph the moon, the sun, the stars, and the horizon at different times of the day and night, looking for anomalies in the heliocentric system. So, I did the same observations with the same camera and I accumulated hundreds of such images.

You have often described your process for this project as akin to that of a “detective” reconstructing a crime scene. Can you elaborate a little more on this analogy, and how this process developed in relation to your previous projects?

This analogy is perhaps slightly misleading and certainly due to a loss in translation. It is important to specify that I am not referring to a detective who imagines what might have happened during an investigation, but really to the re-enactment that takes place when the investigation is more advanced, sometimes even with the accused to check the cohesion of the whole case. During these reconstructions, several actors are present (judges, police officers, scientists, actors, etc.) and re-enact the events on the basis of photographs and testimonies. My approach is similar to that. I analysed the videos and photos conveyed by the flat-earthers and tried to re-stage them as closely as possible, to create a semblance of truth and a confusion in the mind of a viewer, one who has some knowledge on the Flat Earth movement and has perhaps seen these images. The viewer will have the impression that I was there and that this is a real ‘documentary’ about this community.

Actually, it is my first attempt at making staged photographs – I have never done so before for my personal projects.

Many of the titles for your photographs — such as “Buoyancy and density, gravity doesn’t exist” — are presented as bold statements; yet, the photographs themselves, especially if removed from the flat earth context, prompt far more questions than answers. How do you negotiate between mystery and disclosure, as in: how much to conceal to the viewer, and how much to reveal?

It’s a relevant question, and one that was on my mind a lot when I started sharing the project. It was obvious, however, that I wanted to keep a great deal of mystery in the project. As with any conspiracy mechanism, one is quickly confronted with a certain opacity of information. The project remains in essence intriguing, but I have no desire to withhold any kind of information when I am asked questions. The titles are in fact a reappropriation of the titles that the platists have used for their images.

Your photographs seem to be unified by a very consistent consideration of beauty and aesthetics — the play of light and shadow, or a selective colour palette, for example. How important was it for you to express this “beauty” when recreating the so-called experiments of the flat-earthers?

I guess I wanted to make a break from my previous project, for which I had forced myself to be as neutral as possible. Here, I was able to let my singularity flow and to focus on a certain sense of aesthetics. And then, is there anything more beautiful than a sunset over the horizon?

Increasingly precise photo and video manipulation technologies, such as Deepfake, are making it easier for people to manipulate and falsify visual media, and has no doubt been a crucial development in the enduring popularity of the flat earth movement. Do you think this poses a risk to the “integrity” of true documentary photography?

That’s true. However, I still have the feeling that people perceive an image as real. An image, consciously or unconsciously, represents ‘reality’. For example, it has been known for a long time that fashion and beauty photographs are enhanced with computer software. Nevertheless, we are always confronted with this perfection, this deception, and we accept it as being truthful. The same can be said of the automatic filters on smartphones, which smooth the skin or enlarge the eyes for selfies. Having said this, I really don’t think that new technologies will pose a threat to documentary integrity. I do think that deepfakes will have a disastrous impact on the political scene, though, because even if a denial comes later, the false images will linger in the collective unconscious and doubt will remain.

Prominent flat-earther Mark Sargent has stated that the growing popularity of the flat earth movement would not have been possible without YouTube — much of the discourse surrounding the flat earth theory, and the organization of this large community, now takes place online. Do you think that this project would have been possible without these now omnipresent social media platforms?

Definitely not! I started my research within the official flat-earthers websites and their dedicated forums. Even if it was very interesting, the content was very theoretical and followed by arguments with trolls. Once I followed them on social networks, it changed the game!

We’re now several years into the so-called “post-truth era” that many feel began with the 2016 US presidential election, and still far from seeing the end of the COVID-19 pandemic. Do you think you may have approached this project differently were you to begin it now?

I don’t think so. The project has built itself up by itself, by the reflections that are intrinsically linked to it. However, I believe that it is more relevant now than ever and if I were to start it today, I would say to myself that it is too late!

Unfortunately, with the pandemic, I lost 2 years in completing the project. A last important chapter has to take place at the North Pole and I’m going to participate in an artistic residency to achieve this. It has been postponed twice and it should now take place in June 2022.

Seeing as much of your research for this project was conducted from directly within the flat earth community, have there been any reactions toward your work from flat-earthers themselves?

There has only been one real intervention by a Flat Earther (FE) on my work and it coincided with the announcement of my solo exhibition at The Ravestijn Gallery. What I can say is that he didn’t look very pleased! There was no comment on my work but rather a long conspiratorial tirade, all the while quoting people like Einstein and the Red Hot Chilli Peppers. But what really stood out for me was that he used an authority argument, stating that he was an aerospace engineer and private pilot, to start his speech. This introduction reinforced the foundations of my theoretical thinking.

Philippe Braquenier (b. 1985, Belgium) received his BFA in photography from the HELB (Brussels) and has exhibited his works globally — most notably, at the Aperture Foundation in New York, The Venice Biennale (2018), Foto Museum Antwerpen (FOMU) and recently, at the Jimei X Arles International Photo Festival in Xiamen with his project Earth Not A Globe. Having recently concluded its run at The Ravestijn Gallery in Amsterdam, the aforementioned project will be further exhibited at the BPS22 Museum in Charleroi, Belgium, with an opening slated for the 19th of June.

This interview was made possible by the artist and The Ravestijn Gallery. Credits for the photographs in the slider are as follows:

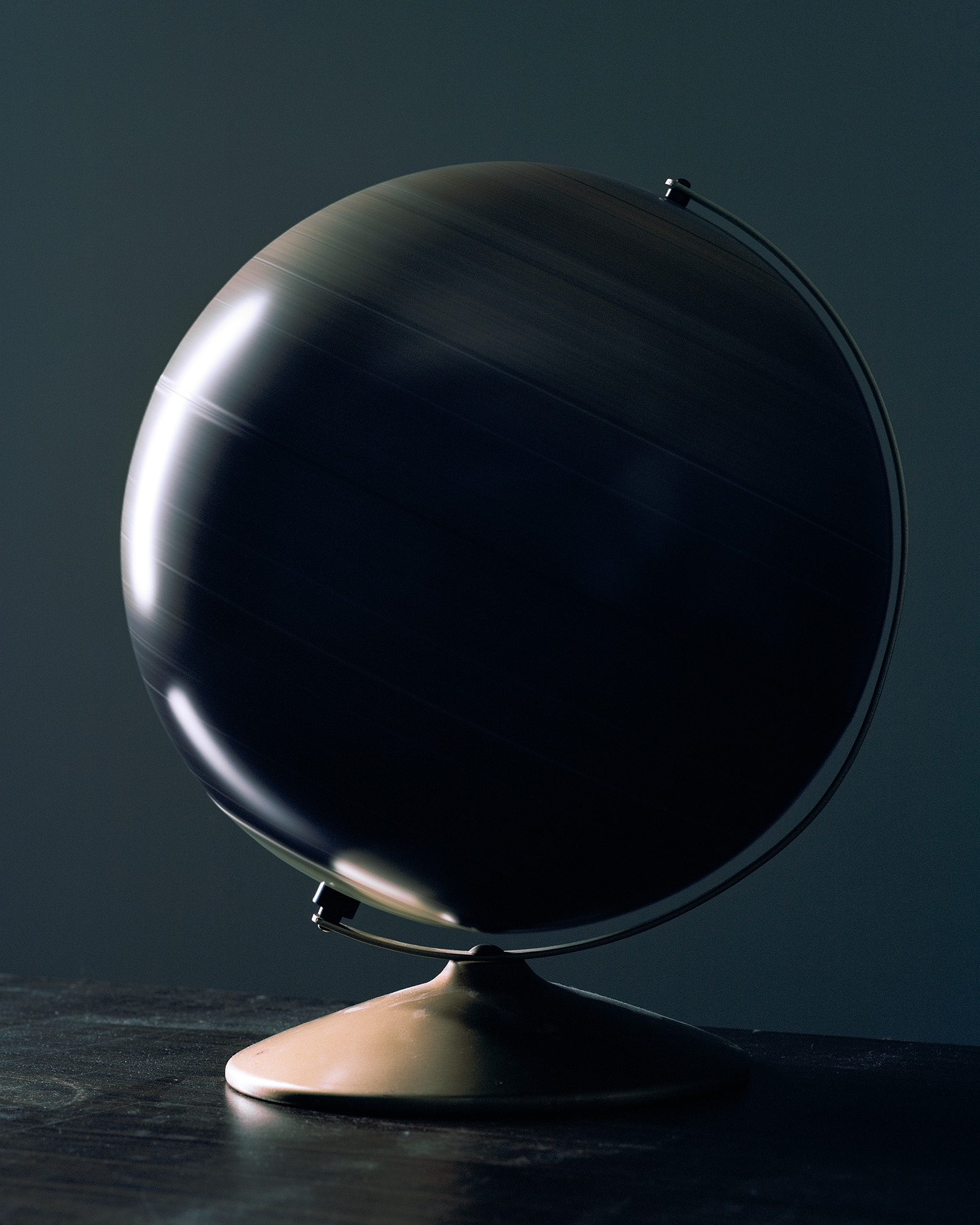

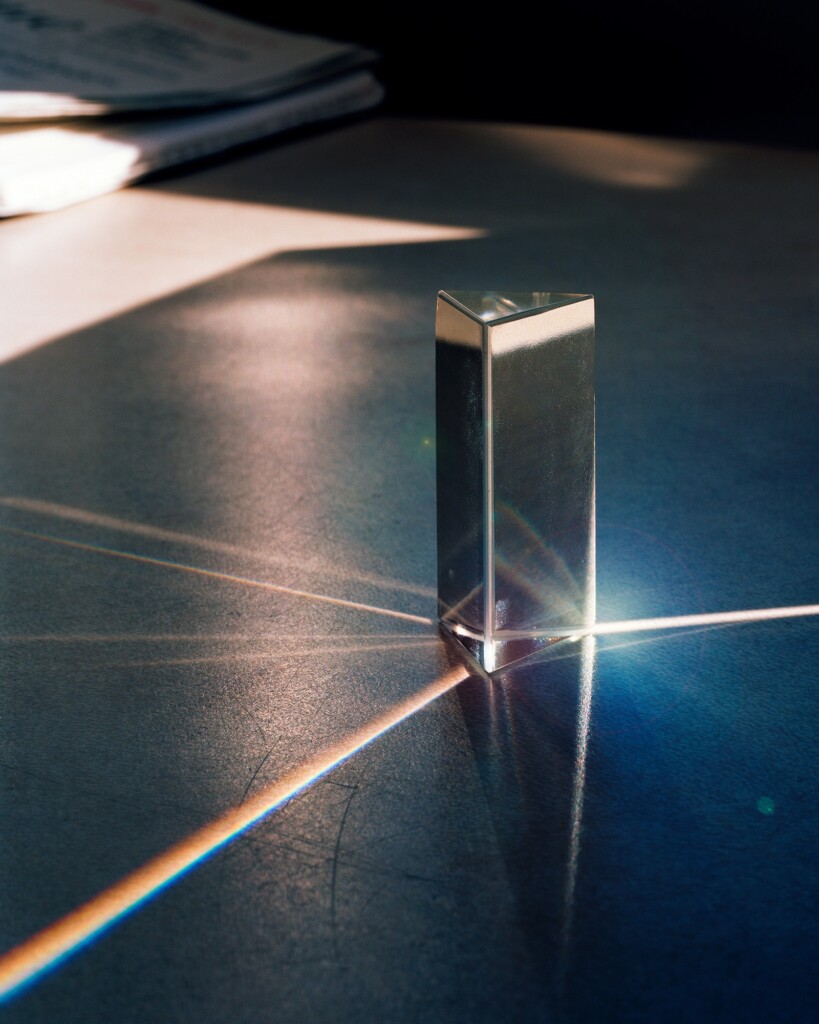

(1) Buoyancy and density, gravity does not exist, 2018; (2) Fading moon and two wandering stars, 2018; (3) Mark, 2018; (4) Rainbows are reflections of the dome firmament, 2018; (5) Southern stars rotation and sacred geometry, 2019; (6) Spinning globe, 2018; (7) The planes help to prove the plane, 2018; (8) The planes help to prove the plane — detail, 2018.

All photographs © Philippe Braquenier, courtesy of The Ravestijn Gallery.