San Benedetto, Benedict of Palermo, São Benedito, Binidittu — the man, born Benedetto Manasseri to enslaved Africans in Sicily in 1524, is known by many names, and as a unique figure of defiance and self-determination…

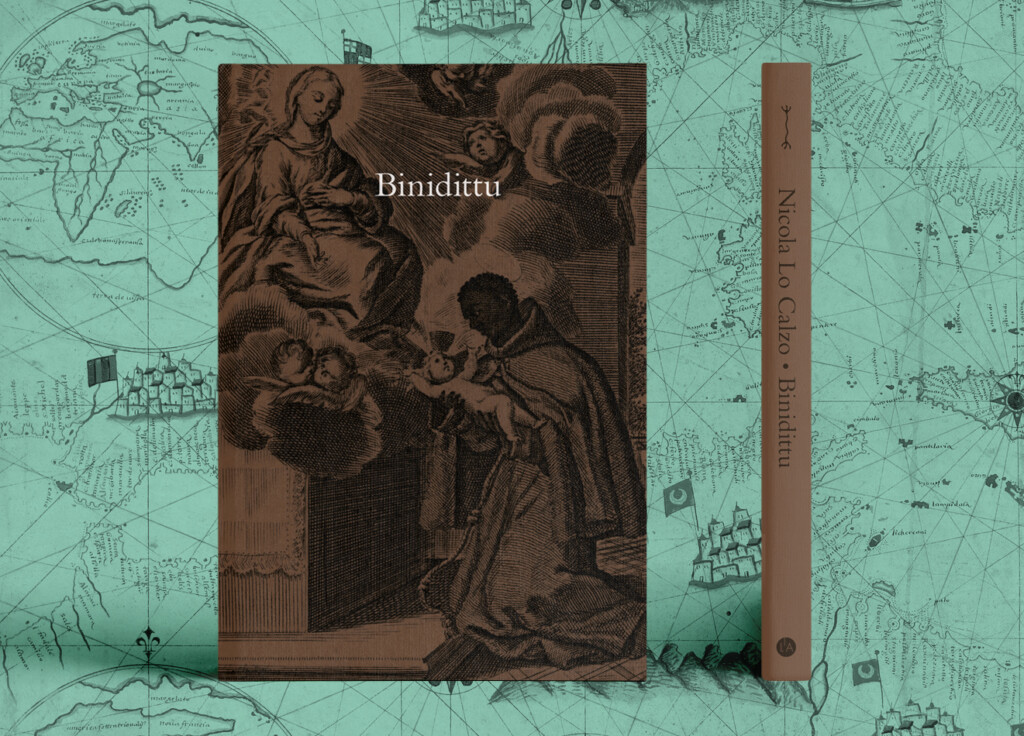

Binidittu, by Nicola Lo Calzo (b. 1979, Italy), is an intricate series that examines the condition of contemporary African migrants in the Meditteranean by virtue of the unifying figure of Saint Benedict, and translates into a contemplative journey through the fields of representation and alienation. In a postcolonial reality, it seems increasingly relevant to re-examine the issues central to ‘Binidittu’, and in this extensive interview with GUP, Lo Calzo sheds some light on the fascinating context of his investigative process.

What was it about Benedict’s story that initially captivated you? Did you know immediately that you wanted him as a central figure in this project?

I became aware of the existence of Benedetto Manasseri during an artistic residency in Colombia, where I was invited to continue my photographic research on the memory of resistances to slavery (the CHAM project). I was immediately intrigued and quickly reconstructed his Atlantic and Mediterranean genealogy. Soon enough, I realised that he was a central figure of modernity, celebrated in all Latin America, yet completely forgotten in Europe.

The poly-modal and multi-centric character of the saint does not allow us to define him univocally: Benedict is a symbol of the African root for the Afro-descendant communities in Latin America, a symbol of brotherhood and humility for the Sicilian devotees, a symbol of struggle against racism for associations of aid to migrants. What fascinated me most is the incredible trajectory of the man Benedict, son of enslaved Africans (to date, we don’t know which part of the continent his parents came from), who, under the pressure of the people of Palermo, reached holiness, even before his formal canonisation in 1807 by the Roman Church, two centuries after his death.

This project aims to contribute to the rediscovery of Benedetto Manasseri, a fundamental figure, albeit forgotten, of modern Western history and of Italian history. But it also wants to induce a reflection on our collective amnesia regarding the historical context in which he evolves and lives, notably the institution of slavery spread in the Mediterranean until the mid-19th century. The Binidittu project furthermore critically questions the deeper connections between the African continent and the Mediterranean: the historical presence of the Afropeans is embodied by Benedict the Moor, as well as by today’s African diaspora which claims its multiple belonging to Europe, Italy, Sicily and the African continent.

“How does one address the “humanitas” of Benedict, as a historical figure, an Afropean man who lived in sixteenth century Spanish Sicily, beyond his holiness, which is the reason for all his post-mortem representations?”

Addressing a topic like slavery — which forms the backbone of Saint Benedict’s personal history, as well as the current treatment of his legacy — is often a very delicate matter. How did this awareness shape your approach to the project, as well as your investigative journey?

My projects are born from an in-depth historical, sociological and cultural research on the representations and speeches produced around and by the communities I work with. The backbone of my research was both Benedict’s humanity — the man beyond the saint — and his holiness. How does one address the “humanitas” of Benedict, as a historical figure, an Afropean man who lived in sixteenth century Spanish Sicily, beyond his holiness, which is the reason for all his post-mortem representations?

In addition to the research on written sources, this awareness has also matured by attending the community of devotees in Santa Maria di Gesù in Palermo and in San Fratello where San Benedetto il Moro was born in 1524. I lived a period in the convent of Santa Maria di Gesù, built by Benedetto when he became the guardian of the convent. My cell was some meters from Benedict’s cell. It felt important to me, in order to breathe in the mysticism of the place, and, in a way, to be closest to him — to his “life places”. For a while I shared my life between the convent and the Ballarò district in Palermo, where I met some Italian or Afro-Italians or Sub-Saharanians residing in Sicily. My conversations with Alagie Jinkang, Alessandro dell’Aira, and later with Igiaba Scego, Doudou Diène, between others, showed me the way and the orientation/direction I wished to give to the whole project.

Furthermore, this growing interest in (and awareness of) such delicate issues as the memory of resistance to slavery, colonialism or racism certainly also stems from my personal experience — the fact that I grew up and evolved in a situation of minority, as a queer person. From my personal condition, I tried to understand the mechanisms of exclusion and, above all, how to build oneself in a situation of minority or marginality..

Oftentimes, your photographs feature the iconography, votives, and relics of or revolving around the figure of Saint Benedict, that you happened to come across in the course of your project. What is, for you, the significance in photographing these devotional objects, and are you perhaps touching upon a parallel between religious iconography and the photographic medium ?

The use of historical iconography is a constitutive part of my artistic practice. Through the articulation of photographs and historical documents, artefacts and images related to Benedict, I build the plot of my narration, overlapping temporalities and multiplying, I hope, the levels of meaning.

The relics, the habit of St. Benedict and the uncorrupted body are the material proof of his earthly life and acquire a symbolic and patrimonial value that goes beyond the religious dimension: they speak to us of the man Benedict, of his condition both as a Franciscan and a black man. They are the very rare proof that this Afropean really lived in Sicily in the sixteenth century. Yet, they speak to us also about an absence: why did Benedetto so suddenly disappear from the Western imagination? Photographing these artefacts was certainly one of the most exciting moments of my research.

“The story of Benedict perfectly represents the complexity of colonial and post-colonial history that must be read and understood starting from the territory in which it belongs.”

Saint Benedict has, throughout history and contemporary times, been referred to by many names. Concurrently, the migration of his story across the world has also resulted in reinterpretations, and in some cases, the ‘whitewashing’ of his legacy. What was your experience working with these topics, and why did you stress the importance of these semantic themes in your book?

The choice to start the Binidittu book with the list of the many names attributed to the saint immediately reveals the global and local, Atlantic and Mediterranean dimension of this historical figure, celebrated from Southern Europe to Latin America, passing through São Tomé. Each name of Benedict corresponds to a specific territory, culture and community.

The story of Benedict perfectly represents the complexity of colonial and post-colonial history that must be read and understood starting from the territory in which it belongs. For this reason, I do not think it is correct to use the American term “whitewashing”, which would translate to a dispossession of Benedict by those Sicilian devotees who today no longer see him as an African and sub-Saharan man. The reality is more complex.

Furthermore, using “whitewashing” would also mean taking for granted that Sicilians are “white” and this is historically wrong. Race is a social construction. Throughout their history, Sicilians have been colonised, racialised and criminalised first in Italy itself – I am thinking of the work of the criminologist Cesare Lombroso – and later, in the United States where, having arrived as immigrants, they have long been marginalised, (the most important lynching of the United States hurt the Sicilians, in New Orleans, March 14, 1891) and they were associated with non-white populations until the 1980s.

For this reason, rather than the “whitewashing” of the saint (which would translate to an American-centric perspective on a Sicilian reality), I prefer to speak of “Sub-Saharan genealogy loss”. At a certain historical moment, for a series of reasons including a Church policy in favour of saints and to the detriment of others, and the decrease of the Afro-descendant population in Sicily, Benedict the Moor is re-appropriated by the local population who make it their own, a local saint like the others. The colour of the skin becomes anecdotal in the eyes of the devotee and is lost in legend. Benedict’s sub-Saharan genealogy is so lost that the colour of his skin is explained through popular tales, the best known of which tells that Benedict, as a child, would have turned black after being accidentally placed in boiling water by his mother!

If we broaden the perspective to the Atlantic world, we realise that a similar process took place, for example, in São Tomé where I discovered the existence of the cult of St. Benedict, imported by the Portuguese Franciscan missionaries. Here the Sao Tomé devotees call their saint São Benedito, without indicating his Palermo origin. When I showed the Sicilian photos to the devotees of the Roça de Boa Entrada where every year a procession is celebrated in his honour, with a statue identical in iconography to that of Palermo, they were very surprised that their São Benedito was also worshipped in Sicily. In this case, St. Benedict has lost his Sicilian genealogy.

In your book, the deeply personal and candid stories of the asylum seekers and migrants of Sicily are deservedly given extreme importance. How did hearing the migrants’ stories inform the way in which you decided to portray them, photographically?

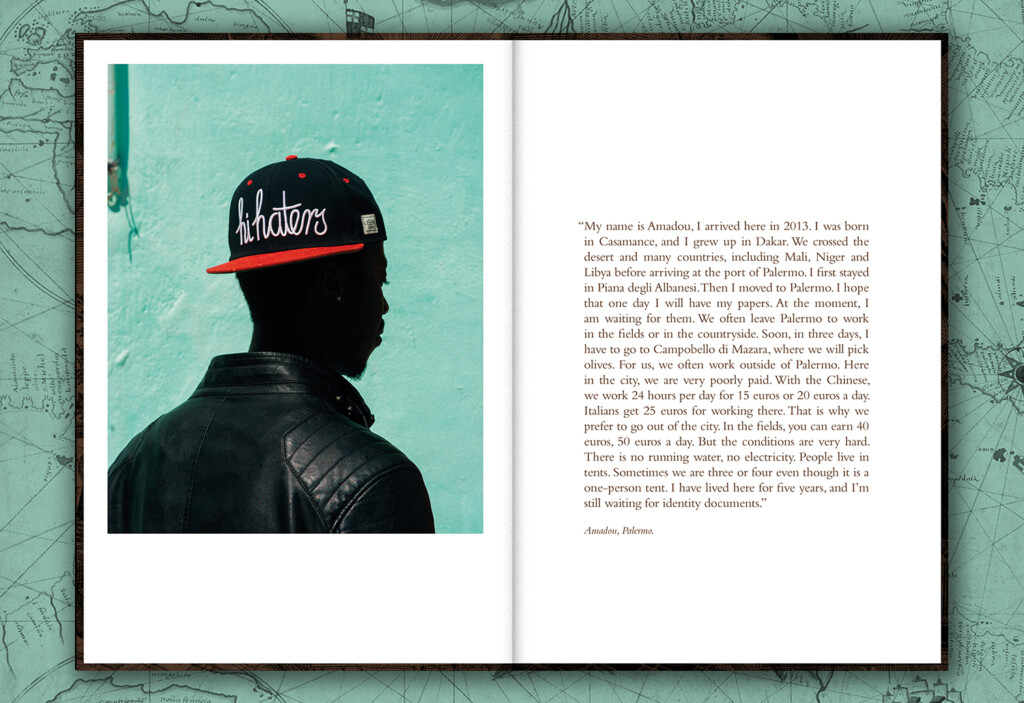

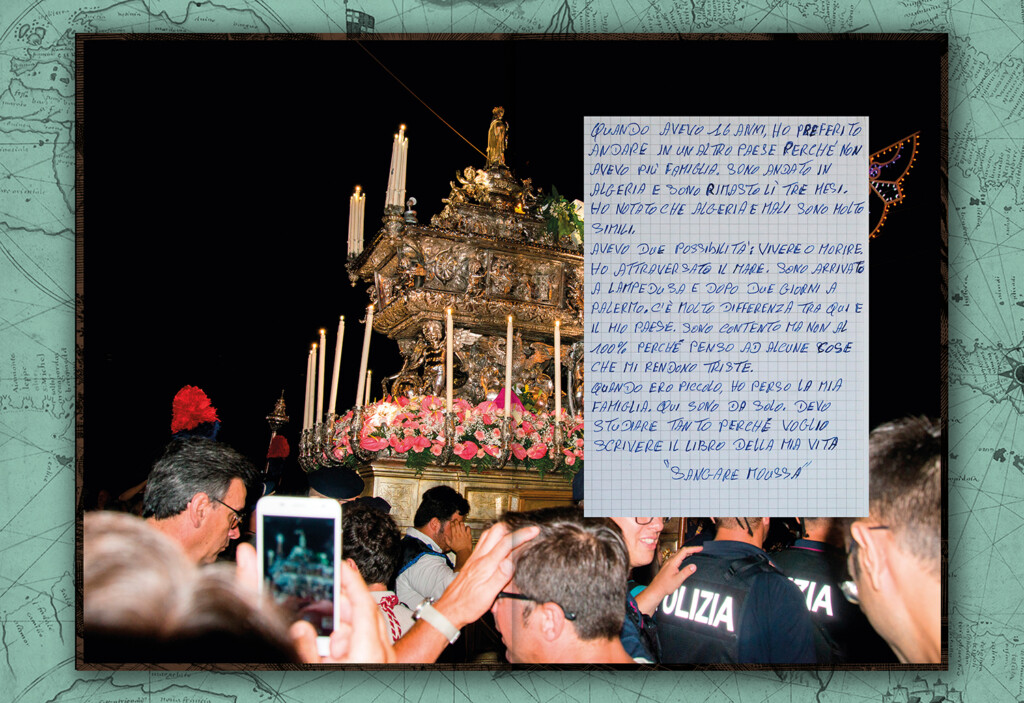

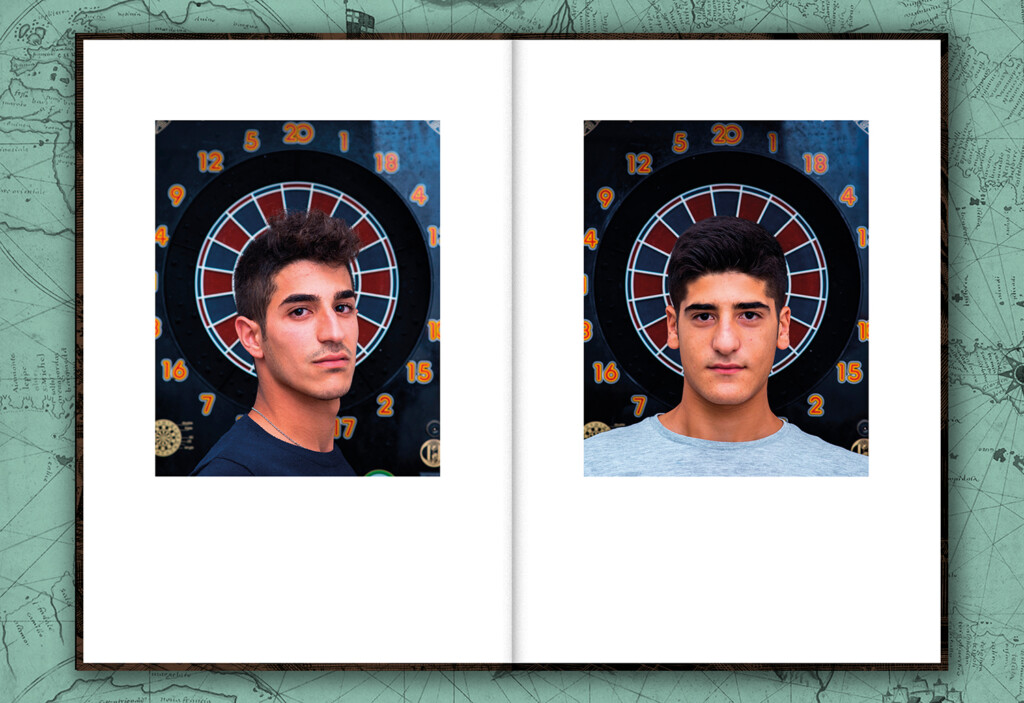

The witnesses reported in the book, among those that I was able to collect, return a fundamental point of view: the individual and complex experience of some young sub-Saharan and Maghreb men and women, their uprooting from their land, the traumatic experience of travel, the racism suffered, but also the reception received, their multiple affiliations (sub-Saharan, Sicilian, Italian), their prospects for the future. Their stories resonate with both the private story of Benedict and the public one as a saint.These stories guided and oriented the whole form of the project.

At the beginning of my research, I was mainly focused on the worship of St. Benedict the Moor in Sicily and the way in which the figure of Benedict is re-appropriated by Sicilian devotees. During the research, I realised how the cult had become local and almost unknown to the rest of the Sicilians. Furthermore, I wondered about the almost total absence of Afro-descendants among the devotees.

Living in Ballarò, the multi-ethnic neighbourhood of Palermo, I encountered Sicilian, Afro-Italian and Sub-Saharan artists and activists, whose stories resonated with Benedict’s experience. Some of them already knew the saint, especially in the context of theatrical and cultural activities organised by some aid centres or by local artists. Others don’t. Through a series of local initiatives, the figure of Benedict is connecting the experiences of Africans, migrant men and women, to whom Benedict is proposed as an updated symbol of universal citizenship and the fight against racism. The initiatives have been set up by different associations, such as Nottedoro, Porcorosso, Donne di Benin City, Mediterraneo Antirazzista and Artemigrante and by local artists such as Igor Scalisi and Martino Lo Cascio. The mayor of Palermo has transformed Benedetto into a real political force by elevating him to a symbol of social peace, against populism and the anti-migrant policy developed by the Italian government.

Then, there was the definitive turning point, the one that convinced me to build the story on the real or possible tension between the experience of migrants and the experiences of St. Benedict’s devotees. It was the meeting with Dieudonné Benedetto, a young Ivorian, who, after arriving in Sicily on the boat, is welcomed into a center run by Franciscans. Here, he discovered the figure of San Benedetto il Moro, and he received the vocation, decided to enter the Franciscan order and become baptised — this an important detail — with the name of Benedict. His story was like a revelation for me, and I saw in it the union point/bridge between these two worlds.

All the photos with the young African diaspora men and women, including the portraits, were taken during moments of their lives, in the places of their daily life, mainly the Baroque district of Ballarò, the beaches of Mondello, the Cantieri della Ziza, the seafront of Palermo, and the fields of olives or oranges where they often end up working.

“Researching written sources is only the first step… only the combining of them with direct oral sources, the musical and choreographic archive, and living cultural practices, can fully embody the memory of slavery and its resistances and give us the point of view of the “vanquished”…”

The research behind each of your projects is both intensive and wide-ranging, encompassing the discovery and use of archival material, as well as contributions from historians, anthropologists, and experts alike. Can you perhaps explain your process, and do you have any advice for those looking to enrich their own work with this kind of meticulous research?

My training as a heritage conservator and architect has certainly played a role in my approach to photography. As I tell my students at ENSAPC (Paris) where I teach as part of a Phd practice-led research, historical and anthropological research on written and iconographic sources is fundamental when we decide to engage in a photographic research on memory, even more so if the memories are marginal or postcolonial. Researching written sources is only the first step. To my point of view, only the combining of them with direct oral sources, the musical and choreographic archive, and living cultural practices, can fully embody the memory of slavery and its resistances and give us the point of view of the “vanquished”, — the point of view of the “lion” in this African proverb: “As long as the lions do not have their historians, hunting stories will always turn to the glory of hunters”.

A little bit on the background of Saint Benedict of Palermo:

Benedict’s parents were resolute to ensure that he would be born as a free man, leading to his life first as a hermit friar at the age of 20, then as part of the Franciscan order at the convent of Santa Maria di Gesù in Palermo, where he remained until his death in 1589. Even in life, devotion to Benedict was widespread, transcending rigid and systematic boundaries of class, with enslaved peoples and elites alike flocking to Santa Maria di Gesù to seek comfort, advice and healing from the devout and humble protector. While veneration and worship of the saint can still be seen today from Latin America to Central Africa, from the Mediterranean to the United States, the 18th century saw a steep decline in his popularity, and in a period where the church’s position on slavery was ambiguous at best, it is no surprise that his Sub-Saharan genealogy — so crucial to the figure of the saint — fell through the cracks. The fraught and nettlesome process of Benedict’s canonization in 1807, is symbolic of this complex, ever-changing legacy, and it is this legacy that Lo Calzo intricately maps in his project, as he navigates the cartographies of collective memory and collective amnesia alike. More information on the life of Benedict can be found in the booklet enclosed with Lo Calzo’s book.