Linda Zhengová

DREAM IS WONDERFUL, YET UNCLEAR

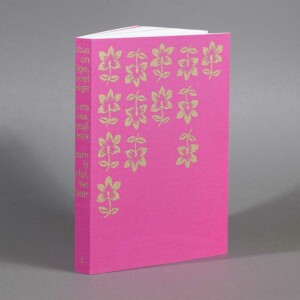

Silk-Screen Cover ,170 x 240 mm, 304 pages

€35

The year 1991 marks a turbulent era. One system collapsed, a new one arrived.

Maria Kapajeva (1976, Estonia) is from Narva, and the epicentre of her hometown is the Kreenholm textile mill, which went through a long redundancy process from 1996 up until its full closure in 2009. Almost everyone in Narva has a relative who used to work at the mill, as did Kapajeva’s parents. The production was gone, the community became forgotten. But life went on.

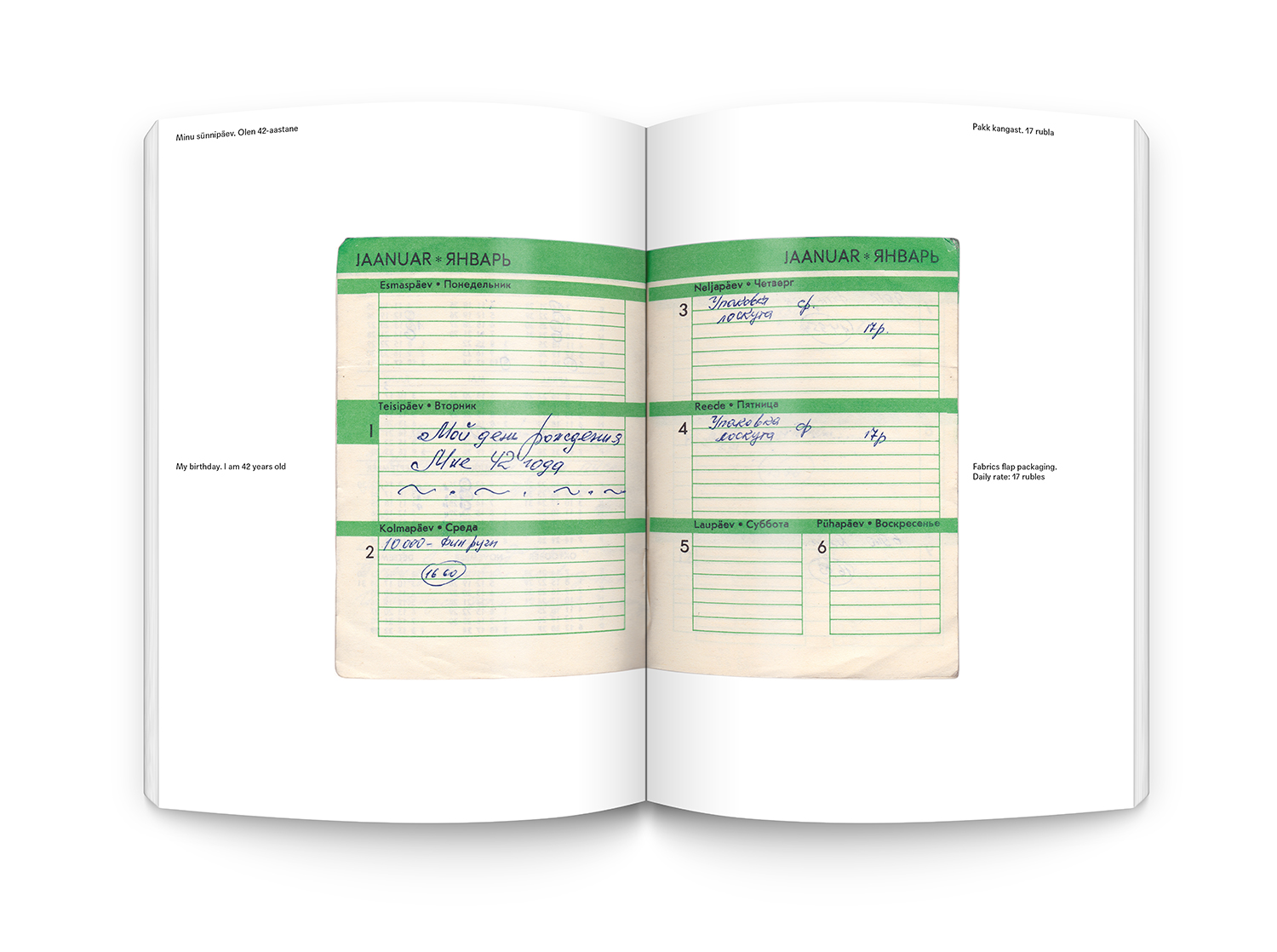

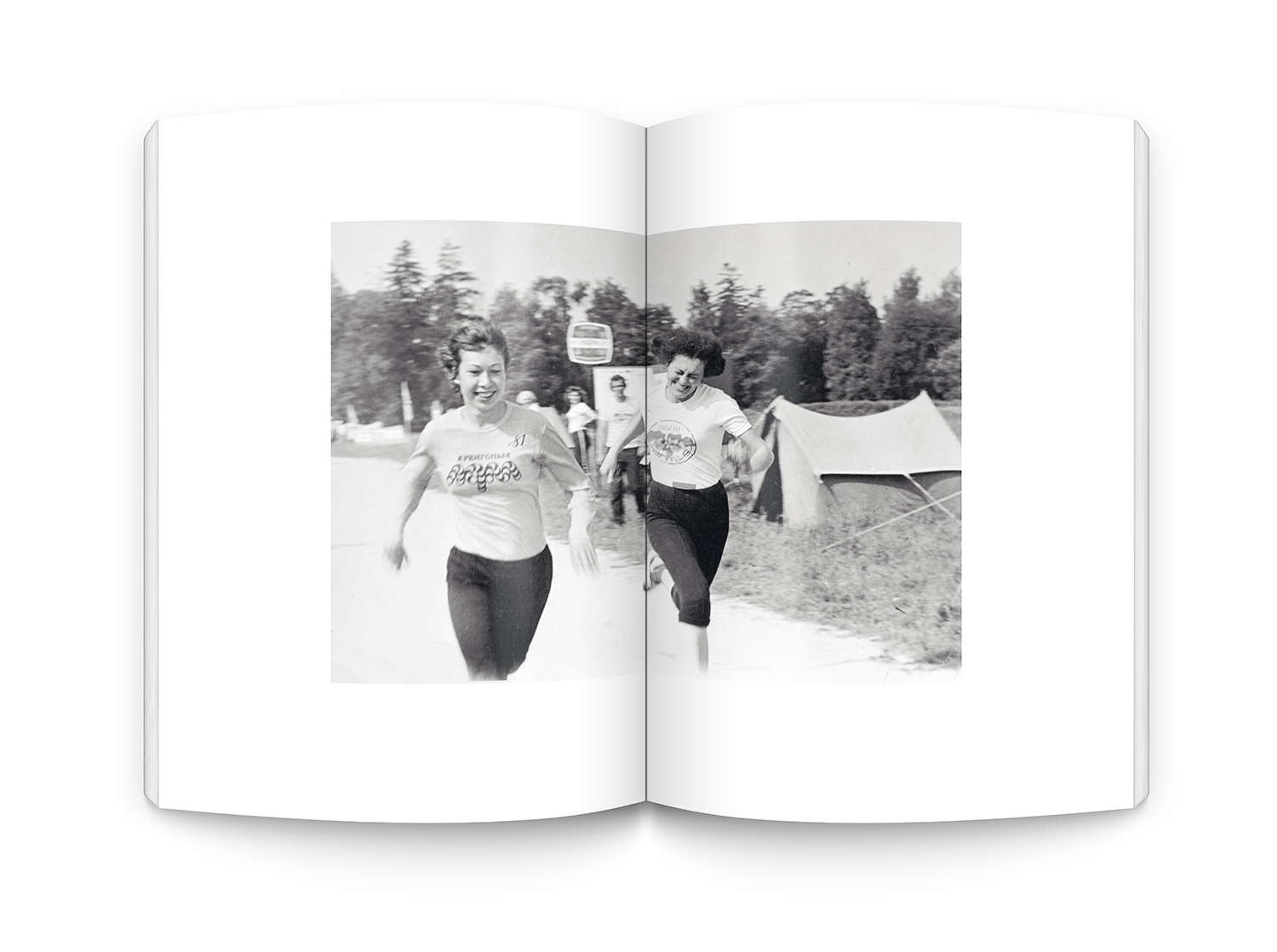

Kapajeva once wished to become a textile designer, just like her mother. Instead, she pursued Economic studies at the University of Tartu. However, an interest in the mill and the urge to preserve collective memory never left her. In 2014, Kapajeva started interviewing the former workers about their memories of the Kreenholm mill, and she collected photographs preserved in their family albums.

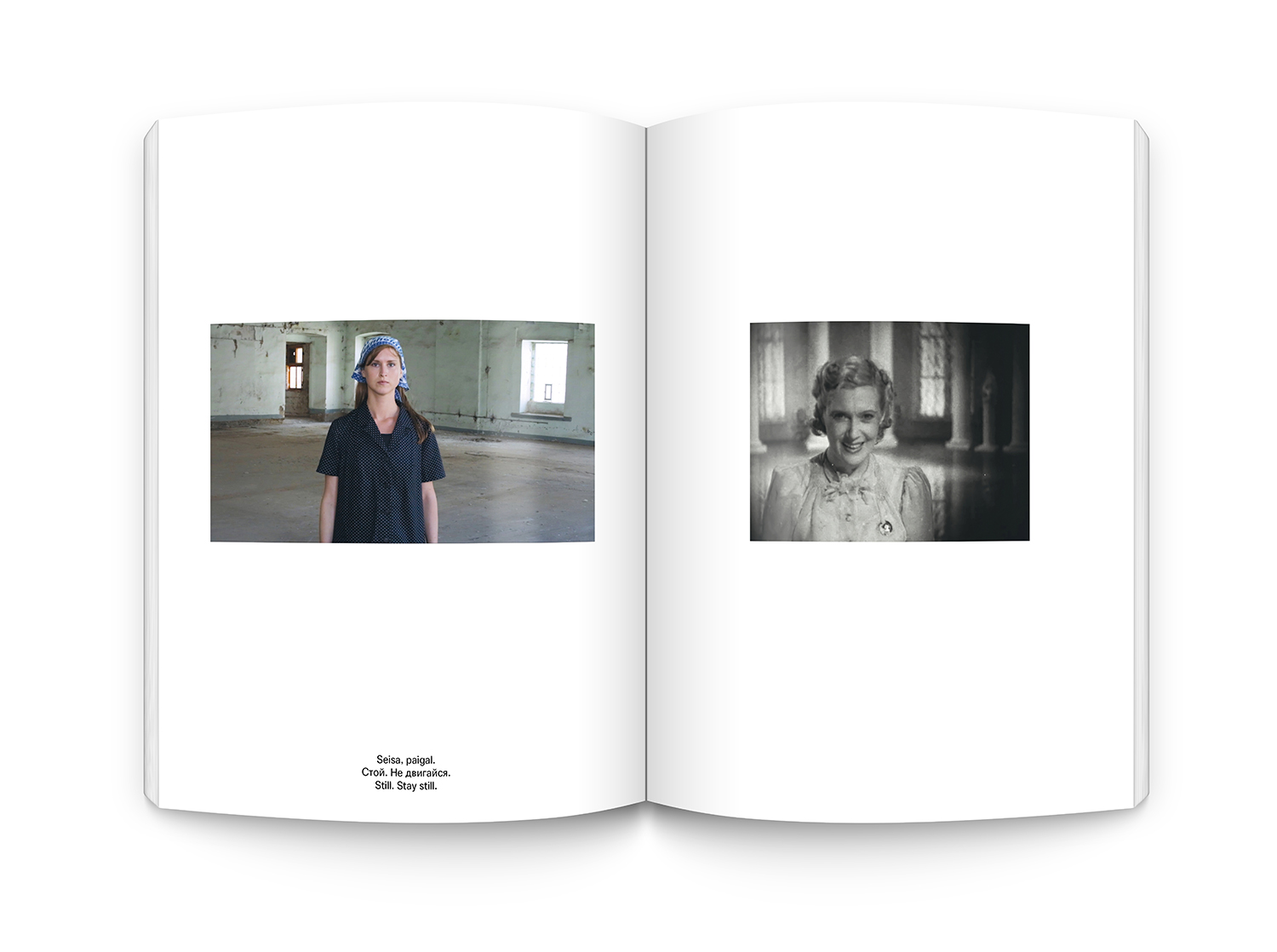

The title of this project is borrowed from the lyrics of ‘March of Enthusiasts’, as featured in the Soviet movie ‘The Bright Way’ (1940). The movie stars Lyubov Orlova in the role of a female weaver, who made her ‘Cinderella’ journey from peasant to Stakhanovite. Due to the doubts raised by the word ‘unclear’, the line from the song was later censored. Consequently, the concept of ‘a wonderful dream’ appears throughout the book, but so does the ambiguity that typifies memories of a Soviet past.

For Kapajeva, the title embodies, besides her own dreams, the former workers’ prospects both then and now, their thoughts as expressed in diaries, but also Soviet ideals as distributed via the cinema, music and photography. Altogether, the book also reflects the hopes of the younger generations of today.

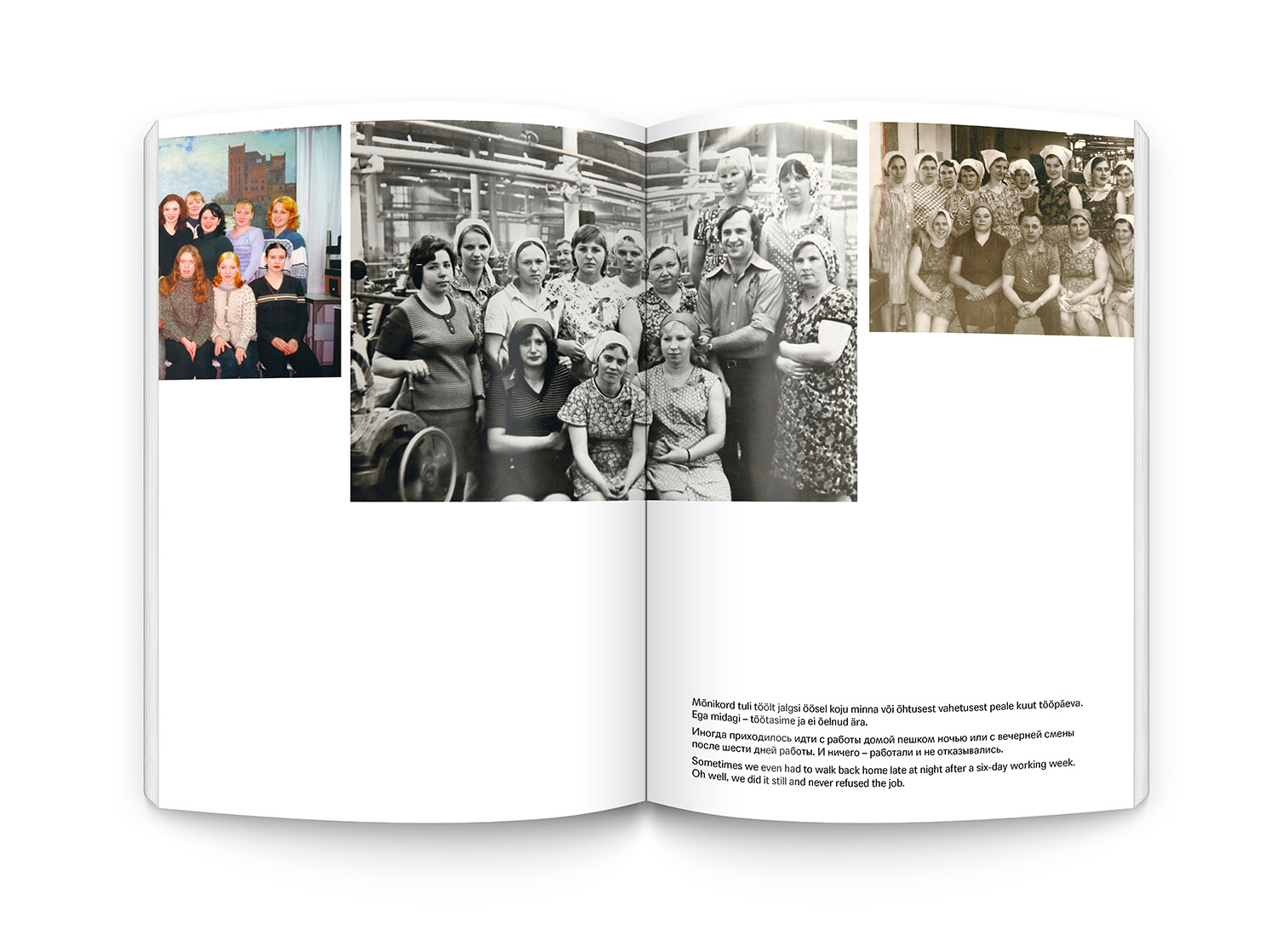

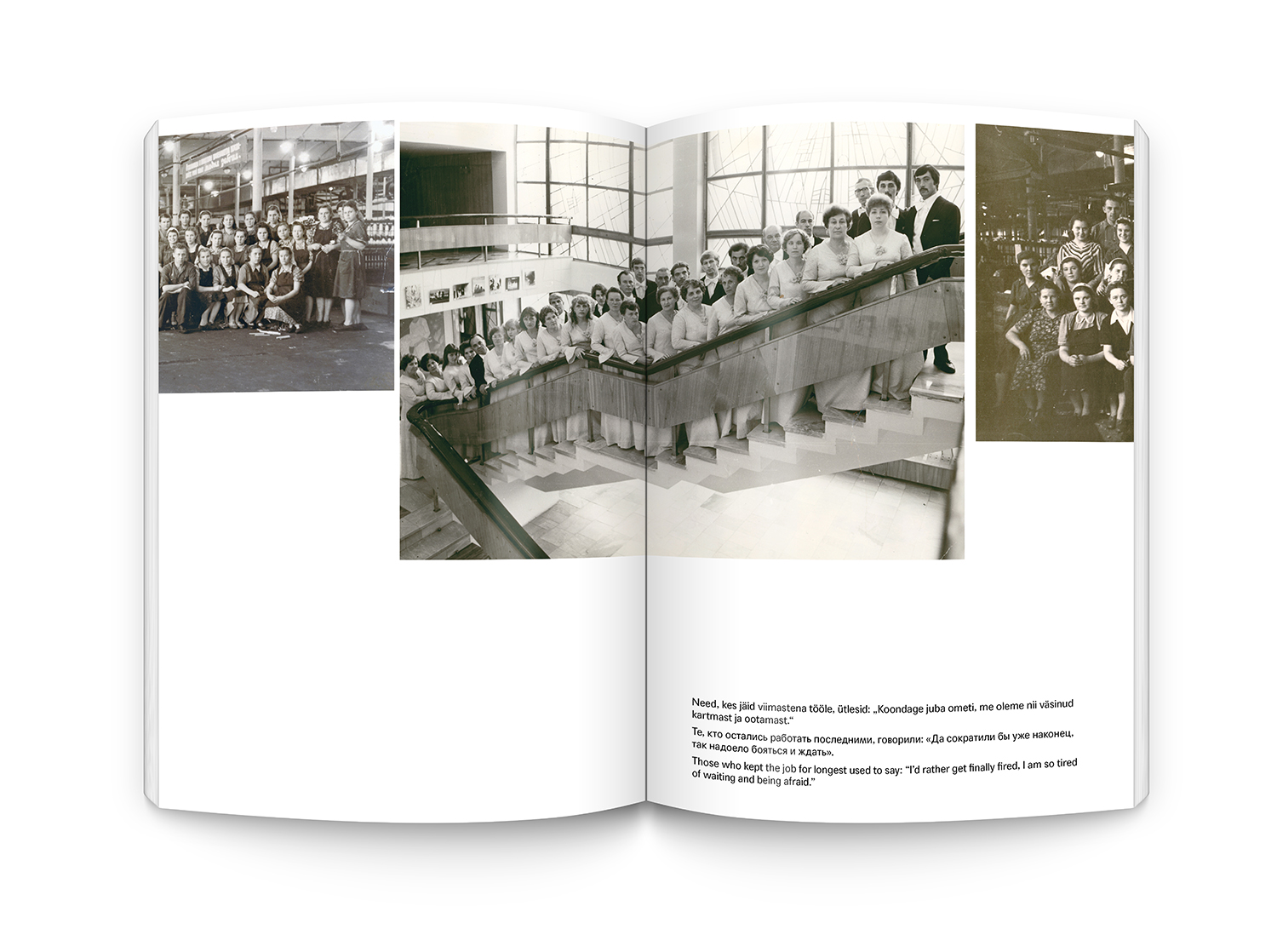

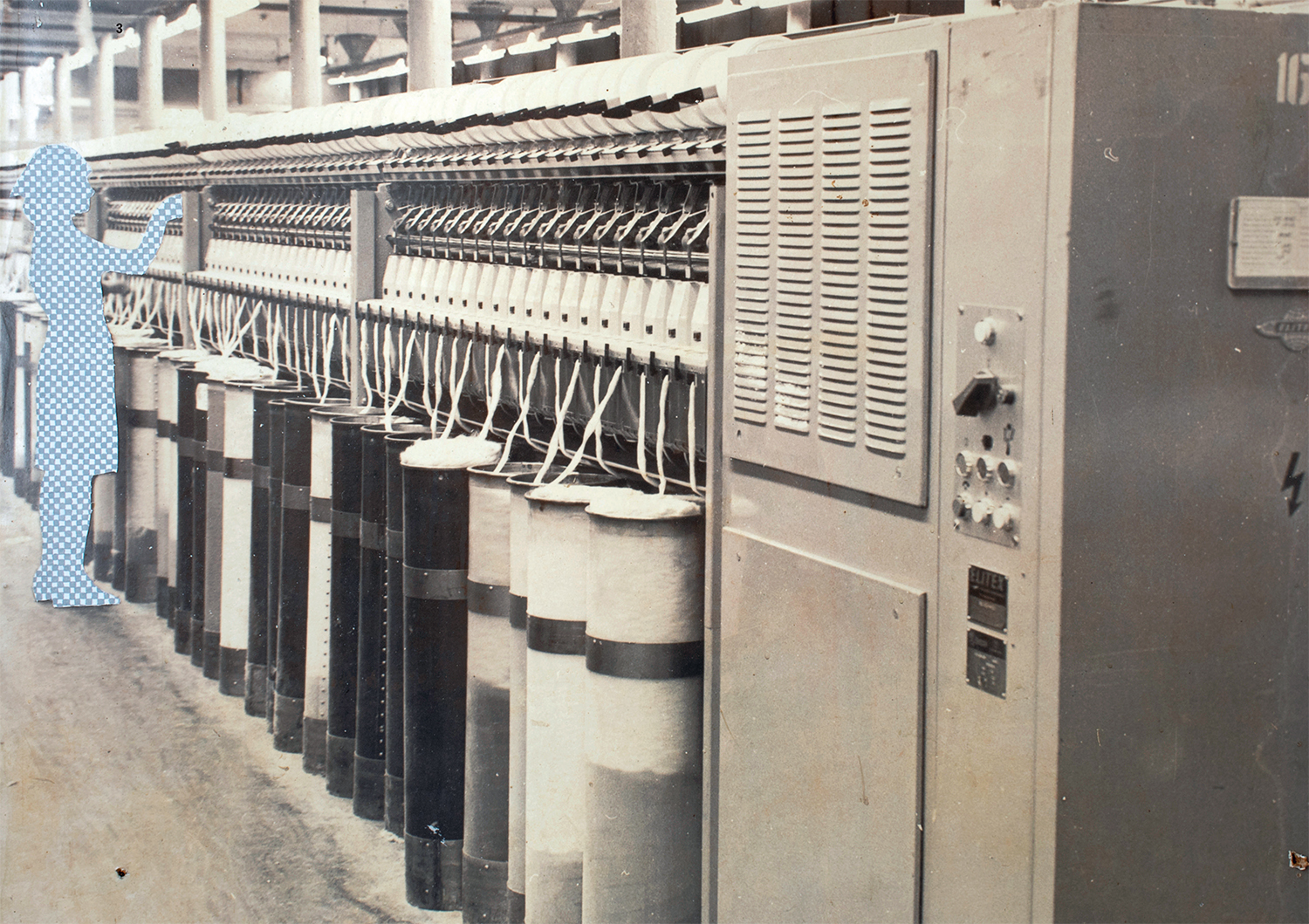

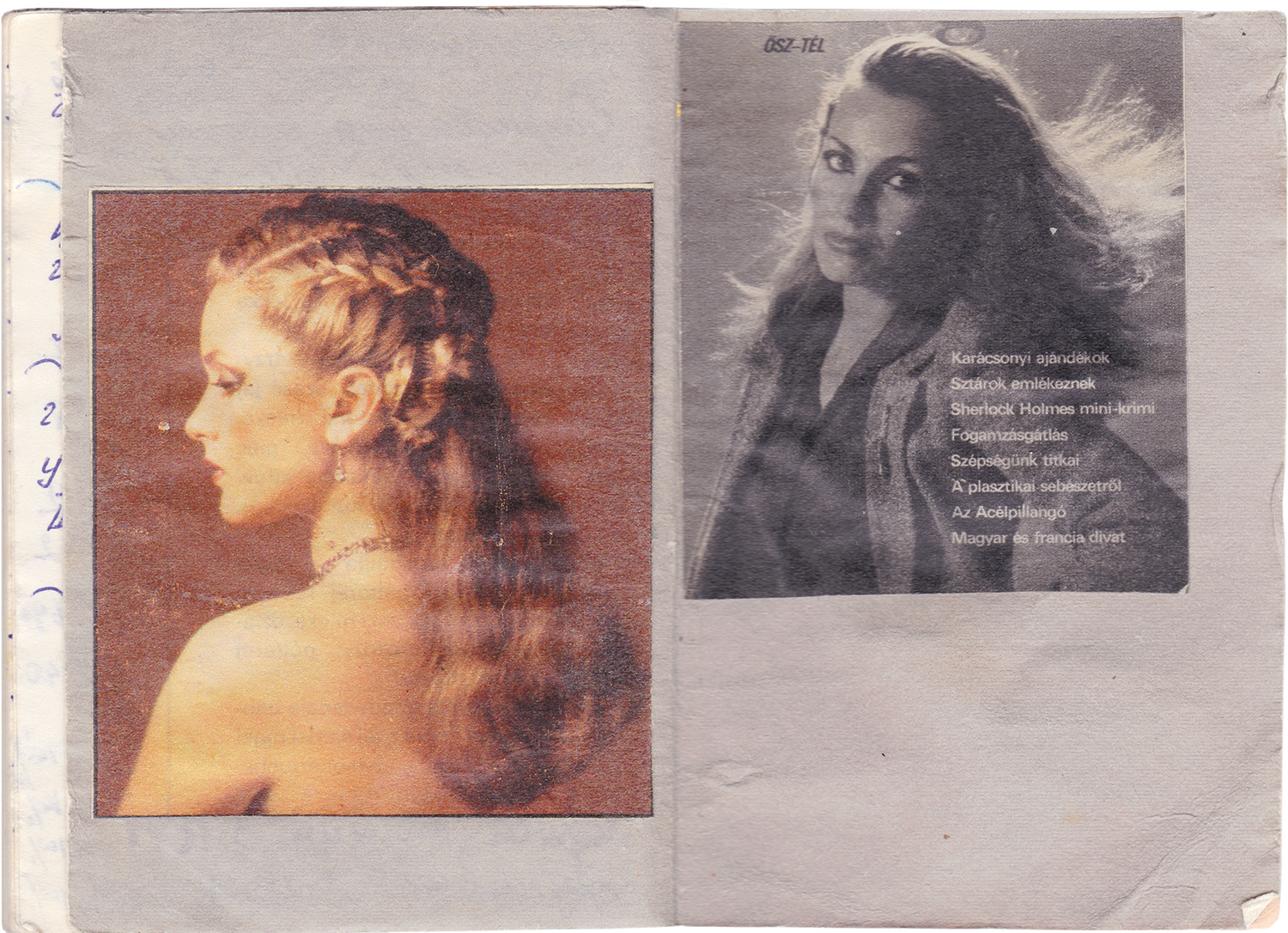

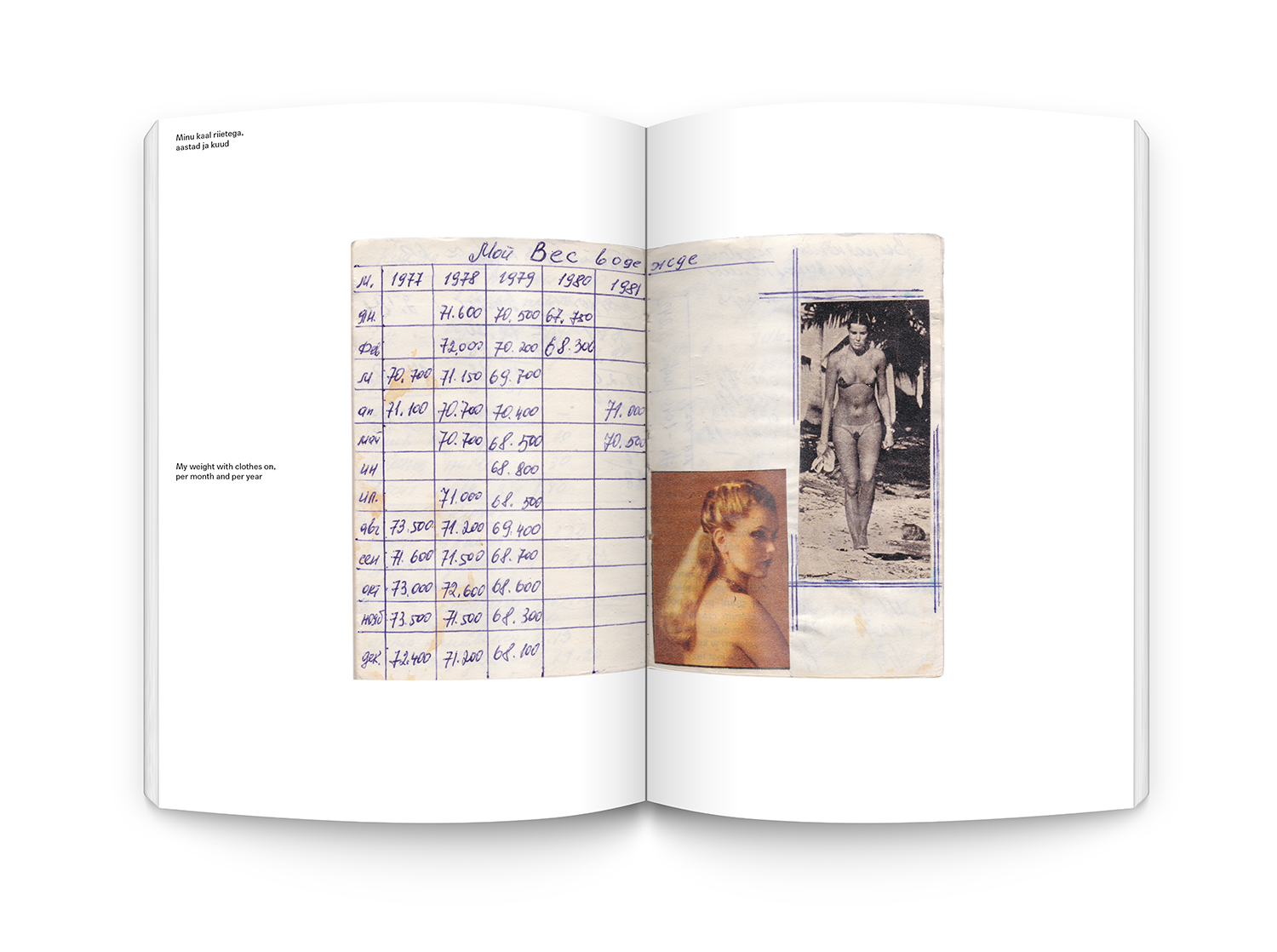

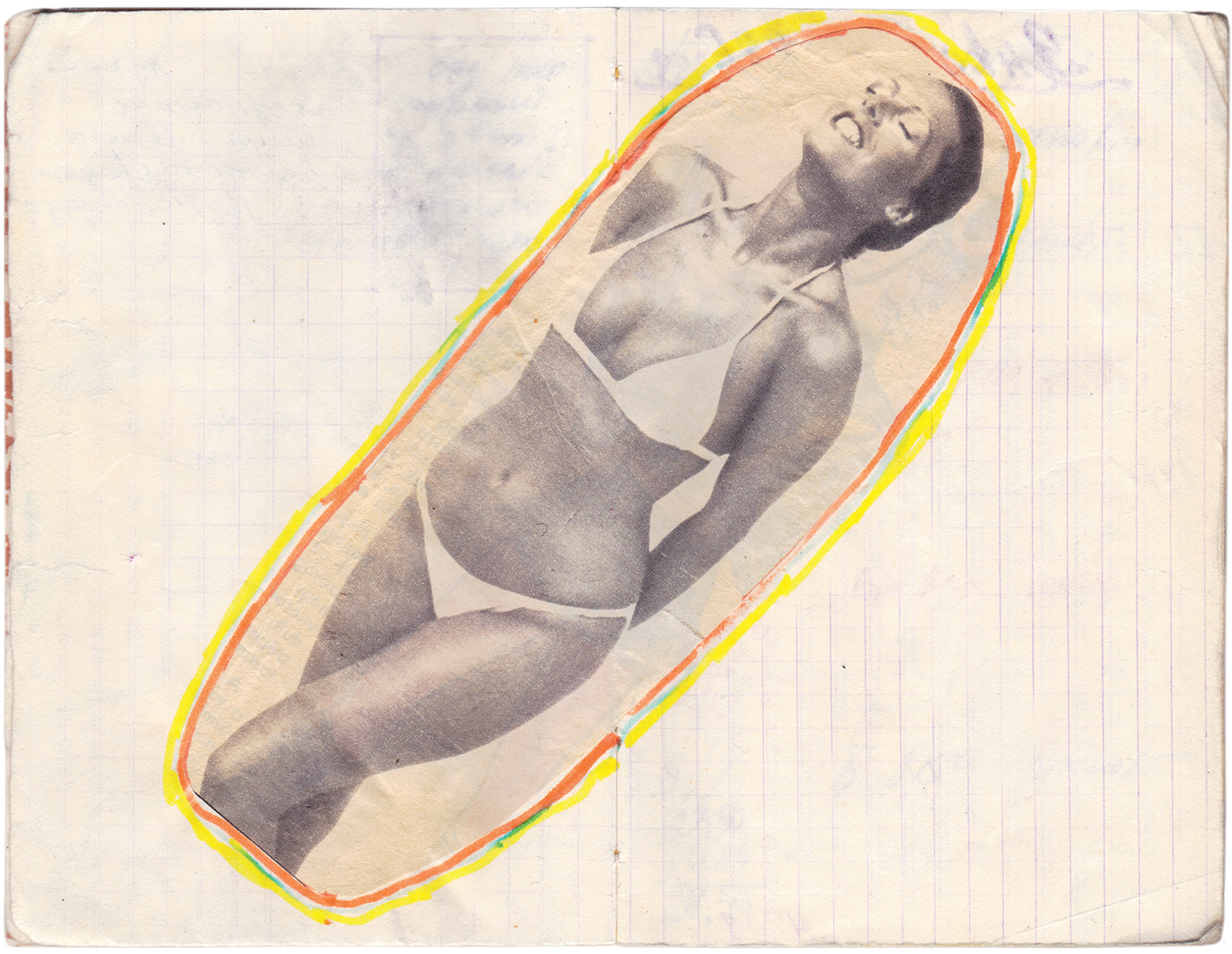

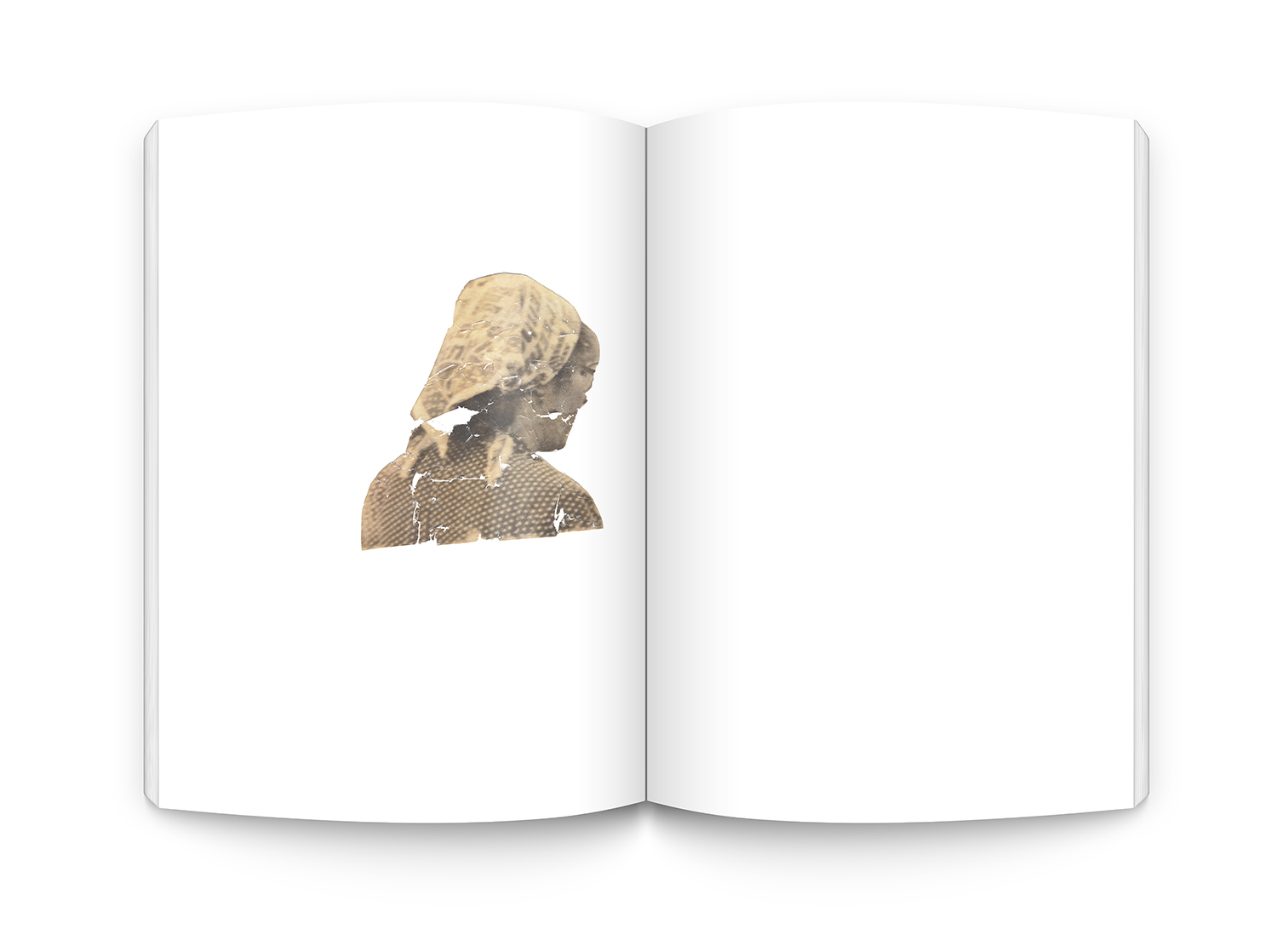

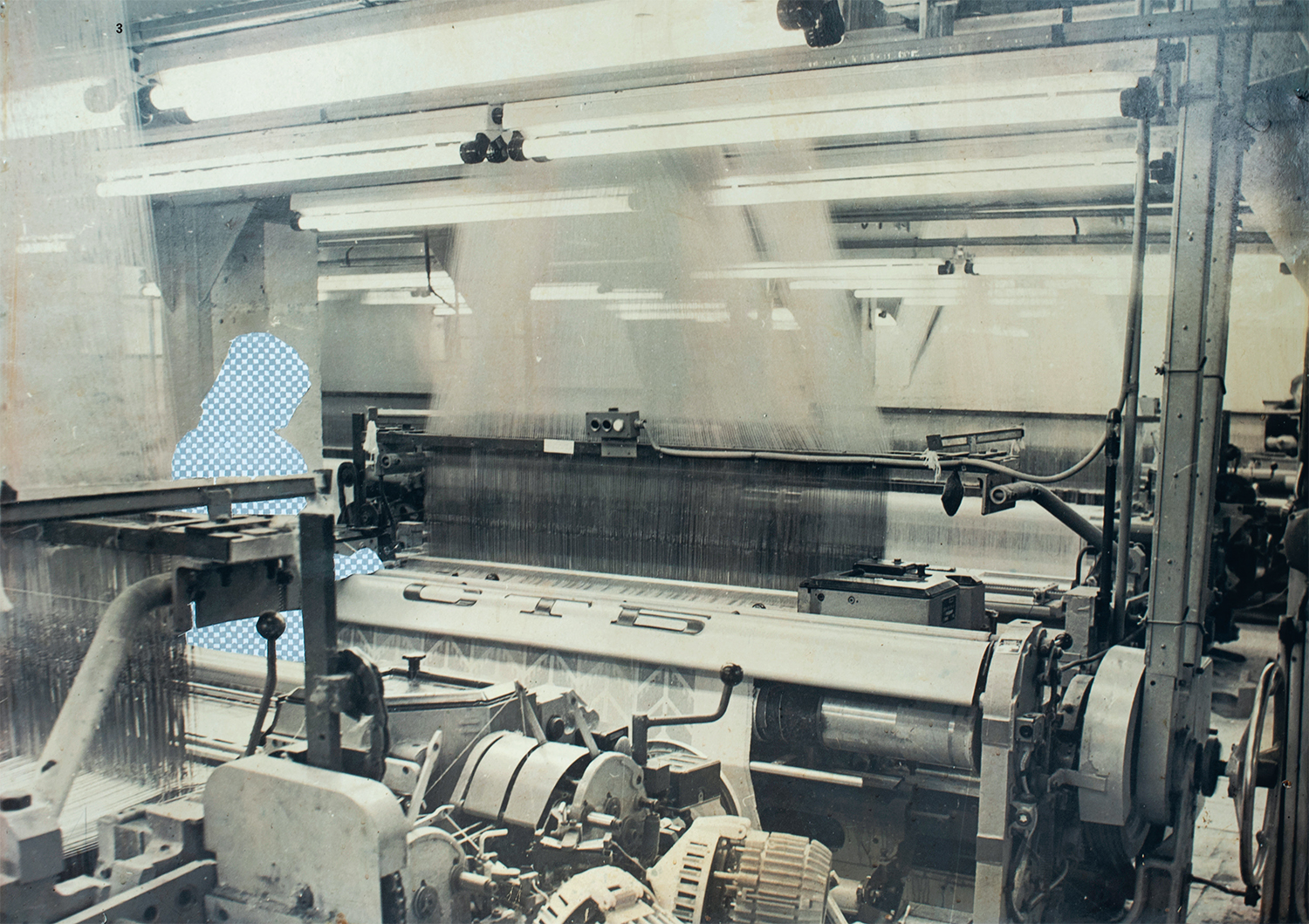

When interviewing the former workers of the textile mill, she received more than 600 digital copies of their photographs – vernacular, professional, group and individual. Kapajeva explains that “the most common images people brought with them were group photographs of their teams, brigades and friends taken at the mill.” The book furthermore includes collages – or ‘cutbacks’, as Kapajeva calls them. “It took me good two months just to walk around the mills and to decide what to do”, she explains. In the end, she opted to carefully cut out the silhouettes of the workers as depicted on posters she found in the vicinity. She then painted the empty spaces with a pattern of Photoshop-background. Additionally, the cut-out figures function as pieces of a puzzle, glued on sheets of white paper.

“(…) the most common images people brought with them were group photographs.”

Art historian Geoffrey Batchen, in his seminal publication ‘Forget me Not: Photography and Remembrance’, focuses on the analysis and meaning of vernacular and family photographs. He explains that “the act of remembering someone is surely also about the positioning of oneself; an affirmation of one’s own place in time and space, establishing our own historical being within a social and historical network of relationships.”

Kapajeva’s way of using the medium of photography indeed turns into an explicit act of remembrance and particularly nostalgia – a kind of delightful sadness. Her careful assemblage and abundance of group portraits ultimately evoke a narrative structure, having the capacity to tell a story of the Kreenholm mill. Additionally, the artist book addresses the fear of forgetting or being forgotten. But what Kapajeva has on offer, first and foremost, is bringing to light a ceaseless process of becoming, a dynamic in which individual identity is malleable and collectively shaped.

(…) many people saw the disintegration of the Soviet Union as a collapse of a great utopia.

How to address the pain of others in the current times? “In Narva, many people saw the disintegration of the Soviet Union as a collapse of a great utopia”, Kapajeva describes. Generally, the mainstream narratives of the economic and political effects largely omit the experiences of daily life of their people and strategies on how to manage their lives in transition. Can, therefore, the memory of daily life of a small community turn into an act of resistance?

‘Dream is Wonderful, yet Unclear’ can be considered as a multi-layered and multi-disciplinary monument dedicated to all the female workers of the textile mill and particularly to Natalja Kapajeva (Kapajeva’s mother), who, as the best worker at the mill, was one of the first workers to be made redundant. Her way of photographing is, therefore, a feminist practice. As Kapajeva elaborates herself, “my work is often about women in transition, whose voices or stories are not told enough or at all. I was born and grew up in the country (Soviet Union), where the equality between men and women was declared within the mainstream communist agenda. With my move to the UK, I started to build up a distance from the rooted narratives, which enlightened other perspectives on women’s situation in the former Soviet territories and in the rest of the world. My work is a journey attempting to understand myself and people like me, often women whose lives operate outside the mainstream. Thereby, I create with the hope for the world to become more inclusive.”

(…) I create with the hope for the world to become more inclusive.

‘Dream is Wonderful, yet Unclear’ is written in three languages – Estonian, Russian and English, designed by Jaan Evart (EE,NL), contributed by Liisa Kaljula (EE), Philipp Dorl (UK) and supported by the Cultural Endowment of Estonia, British Council in Estonia, Creative Europe Programme of the European Union, A Woman’s Work and Gallery of Photography Ireland. The book is currently available for pre-orders here.