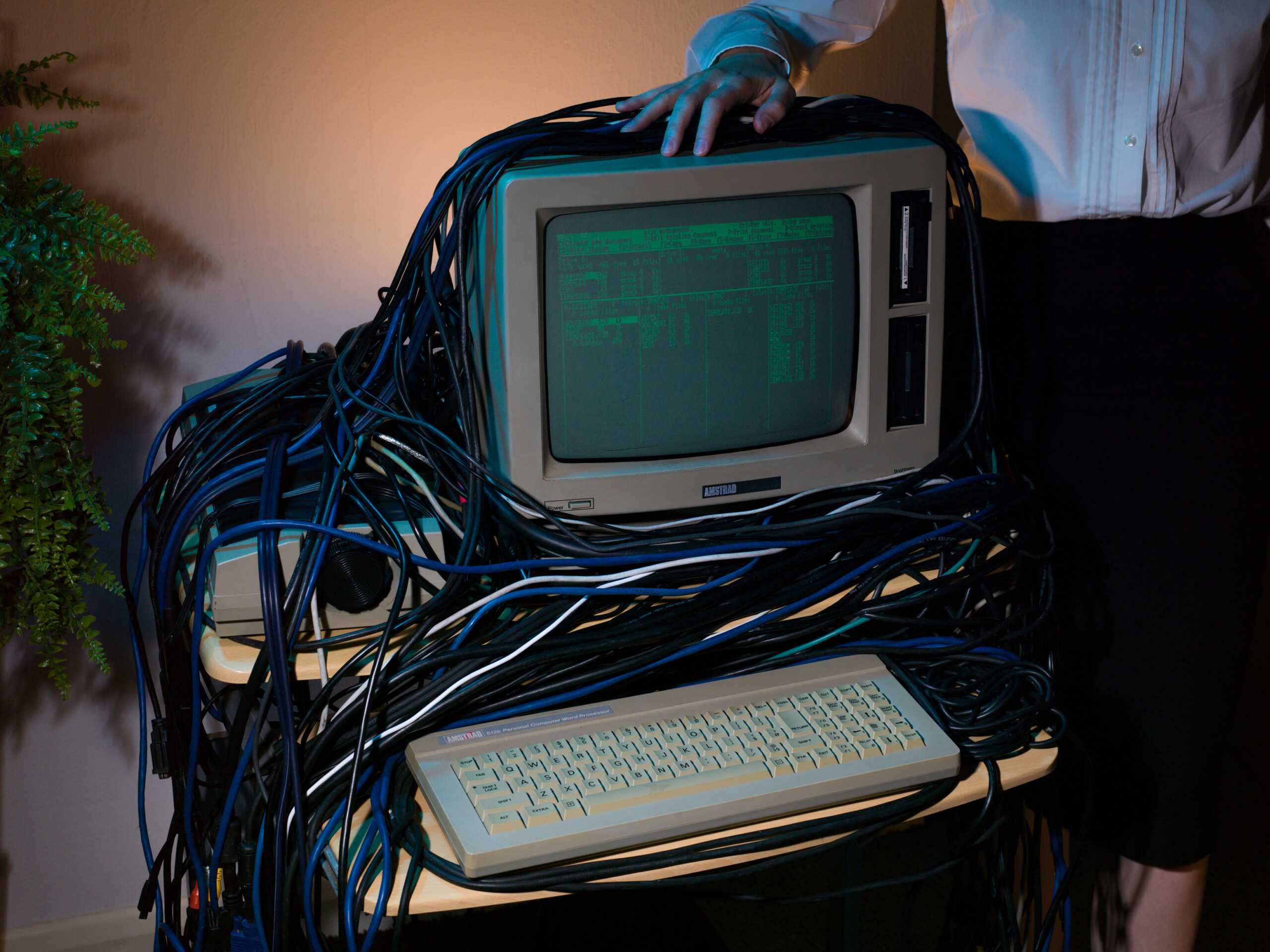

The cult of technology takes center stage in Anabela Pinto’s photographic series Precious Things, as she explores mankind’s precarious relationship with the devices that have come to dominate our social and domestic lives. Obsolete technologies of a bygone era collide with the strangely mechanical human protagonists of Pinto’s photographs, all of whom are bathed in the familiar ghostly, blue-tinged light of television screens.

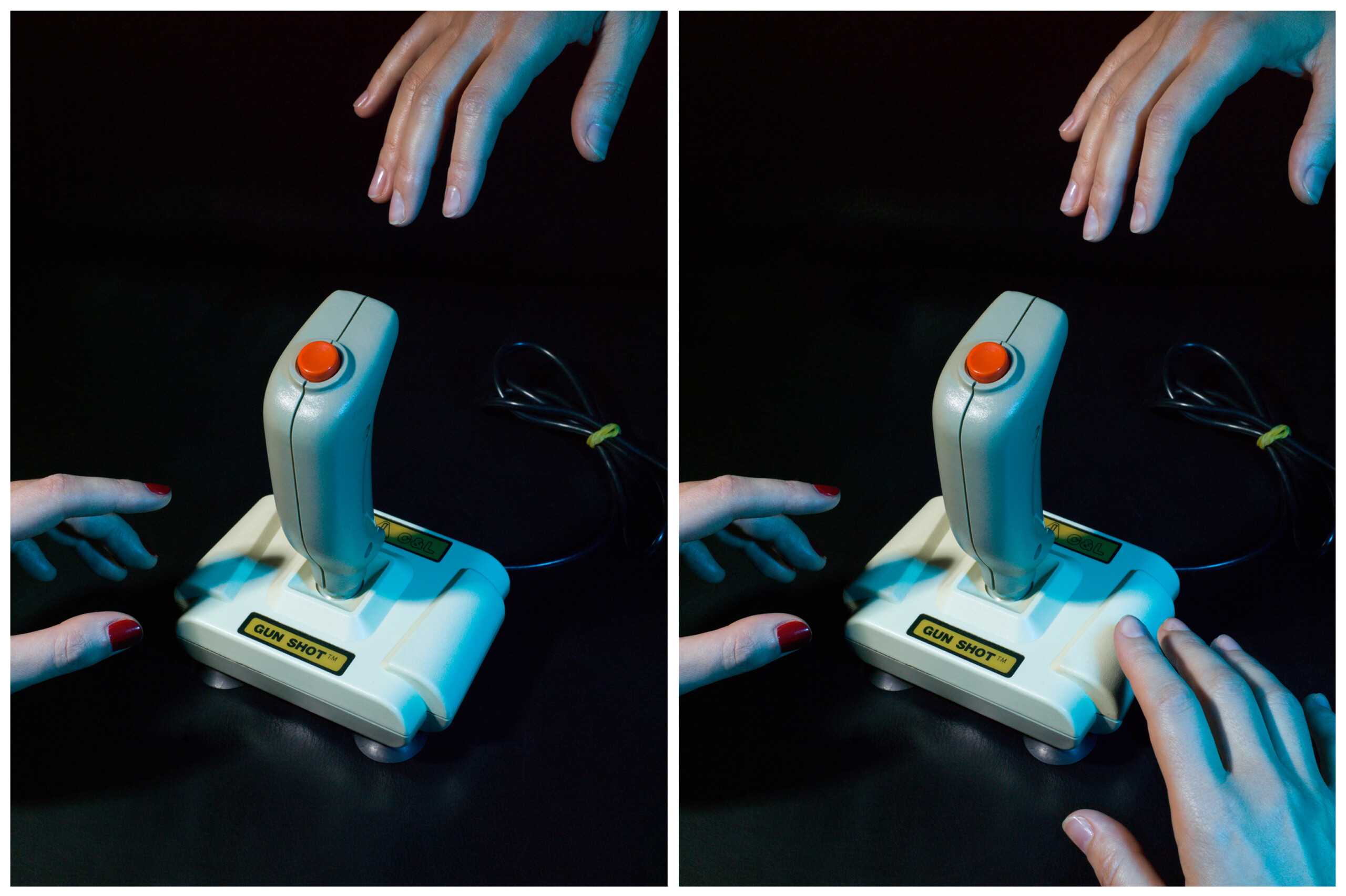

One could say that mankind’s contemporary relationship with technology has been characterized by a vacillation between our inexorable reliance upon it and our suspicion towards its potentially hostile intentions. This schizophrenic affair is no doubt aided by the powerful force of consumer culture, and one can see the influence of advertising and commercial photography in the images of Pinto — the screens, machines and devices she portrays are treated in an almost fetishistic manner, and are clearly not subservient to the human subjects that use them.

The cinematic language of her imagery pays homage to the aesthetics of David Cronenberg’s 1983 cult film Videodrome, an eerily prophetic look into how media, and the technology that houses it, informs and dictates our perception of reality. Cronenberg saw technology as an extension of the human body — we continually activate and perpetuate its physical and spiritual presence in our lives, extending its purpose from mere commodity to indispensable necessity. Whether we like it or not, human interconnectivity on a global scale has been redefined by the vistas of digital technology, and the ubiquity of screens in our domestic spaces only serves to reinforce our dependence on visual media.

The screens and other such technological devices Pinto chooses to portray are most often those one could qualify as “obsolete”: the old tape recorders now gathering dust in attics, the VCRs one can’t bear to throw away for nostalgia’s sake, or the boxy analog televisions that recall a time when screens couldn’t simply fit into one’s pocket. Though Pinto admits an autobiographical basis for her use of such technologies — they no doubt evoke a sentimentality for the 80’s and 90’s — there has been a steadily growing interest in such objects in recent times, as mankind has become increasingly enamored with the idea of a “throwback” to better and simpler days.

Technology seeks to assert itself as an increasingly immersive experience, full of wondrous potential and sinister possibilities in equal measure. Is our renewed interest for analog cameras, record players and old, classic television units unwittingly dictated by a latent fear for technology’s frighteningly rapid advancement?

While Pinto’s constructed scenes do not appear to illustrate a particular narrative, her calculated use of mise-en-scene is designed to reinforce the strange and often affectionate relationship humans have with these inanimate objects of desire. There is a stillness to her human protagonists that seems to extend beyond their frozen state in the photographs, as if becoming inanimate objects themselves. The iconic line from ‘Videodrome’ — long live the new flesh — comes to mind, uttered by the film’s protagonist as he knowingly and intentionally succumbs to the cult of technology that has come to entirely alter his perception of reality. The line between man and machine, the eye and the screen is no longer distinguishable, offering up a sinister prediction of our future relationship with the machines we can’t seem to negate from our lives.

Anabela Pinto is a Portuguese artist and photographer living in London. She was chosen as one of the talents for the 2020 edition of Fresh Eyes.