NORA UITTERLINDEN

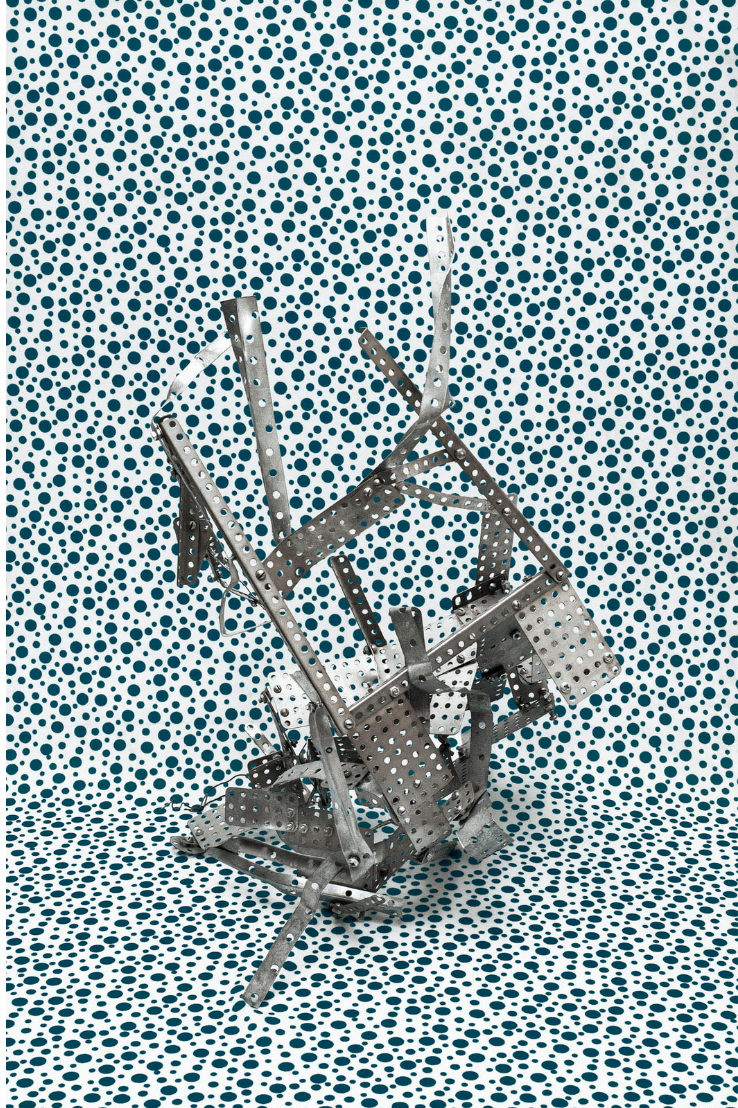

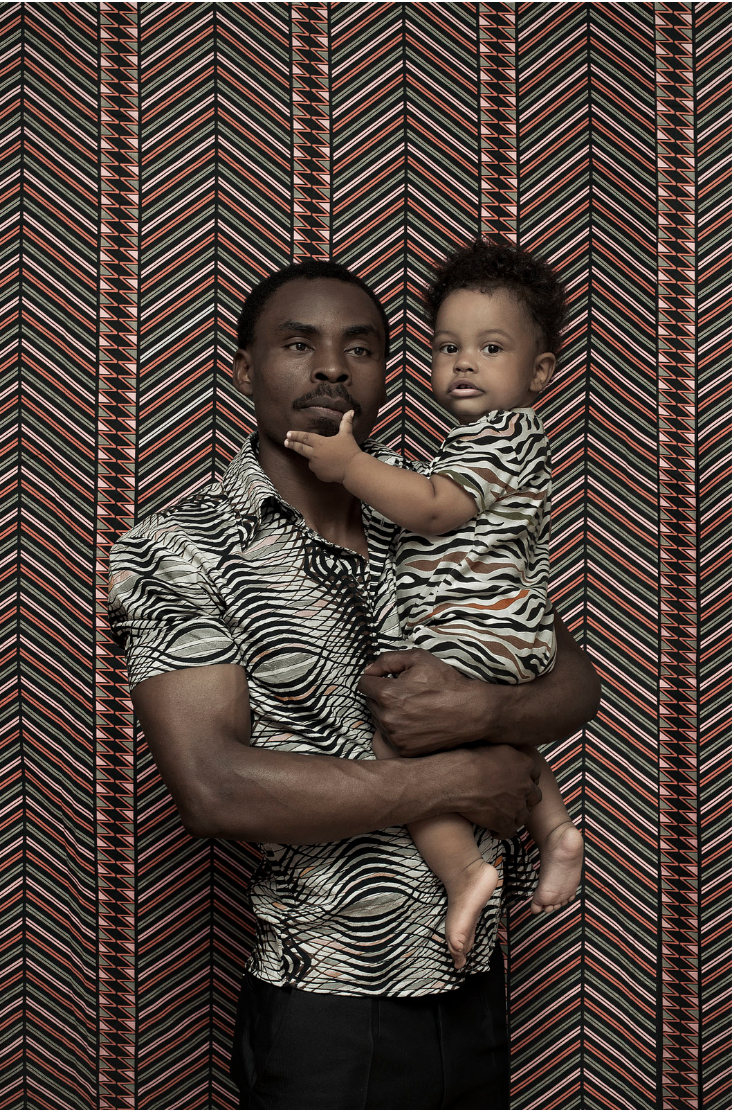

Polish intermedia artist Natalia Wiernik (b. 1989) makes photos in which the foreground blends into the background. The people and objects in her photos lose their boundaries, and become a continuation of their surroundings. Wiernik tells GUP how she started working on this type of images, how she dealt with the criticism and why she embraces ambiguity.

When was the first time you created an image with this effect of your subject and the background seeming to merge?

A few years ago, before I started my first photo project, I made a photo for the cover of a book called Tango, by the Polish writer Sławomir Mrożek. I set up a table with a cloth hanging over it, put some plastic flowers, cards and bottles on top, and took photos of it as a still life. When I was working on the pictures on my computer, I saw that the objects on the table seemed to be in camouflage: they fitted perfectly within the pattern of the table cloth. I said: “How strange, everything disappeared!” I hadn’t seen it with my naked eye. But I immediately liked the effect, so from then on, I started using it in my work.

Where do you find the backdrops and the objects for you images?

I found a little room at the Jan Matejko Academy of Fine Arts in Cracow where I was studying at the time, and now working. The small room was a mess, it was filled with a large collection of fabrics and objects, many of which were from the communist-era. The objects were collected by generations of professors, who used them for still lifes in drawing and painting classes. I found myself going to this wonderful closet quite often to pick objects for my images. But I also started building my own collection. I often go to flea markets here in Cracow.

“I like it that there are no sure answers when you look at the images”

Is there any fabric or object with a special story?

One day I bought a jacket in a second-hand store. I instantly liked the jacket because it had a comb in the pocket from the previous owner. The lining of the jacket was black, with white roses on it. I was breastfeeding at the time, and one day the dried milk on my bra looked exactly like the white roses on the lining of the jacket. So I took a photo of that. Afterward, I never put the bra in the washing machine, I put it in my collection instead.

In the case of the bra and the jacket, you found a similarity between two pieces of clothing, but you also use this approach in your portraits, in which you portray people who may or may not be ‘real’ families. How does that work?

Sometimes I meet a person in the streets, and I want them to be in a photo with another person I met. For example, in one image there are two little girls with a grey man in the middle. The girls are sisters, but the man is a complete stranger to them. Even the cat is from another family. I thought these four could look like a family together. I like to highlight the idea that people can form ‘families’ on the basis of similarities that go beyond blood ties. I use the backdrops to create a visual connection between them.

“The role, not only of photography but of art, is to change people’s perspective, to refresh it”

You received a lot of criticism for this series, called The Protagonists. What was it about?

It was controversial for a lot of people. There’s a problem – maybe not only in Poland – if you question the definition of what a family is. People asked me: “How could a man with a dog be a family? Or two ladies?” This criticism actually made me more confident to continue the project. People so easily judge others who are not like them. So I play with people’s expectations, I have some real families in the series and some fictive families. It’s up to the viewer to believe it is a ‘real’ family or not. I like it that there are no sure answers when you look at the images; there’s only ambiguity.

Do you think photos can change people’s perspective?

Yes, I think that artists can find diagnoses for what’s happening in society. The role, not only of photography but of art, is to change people’s perspective, to refresh it. Art can make people more aware of what they see, and what they think they see.

You call photos ‘installations’. Why?

I have always been interested in where exactly installations, sculpture and photography end, and where performative activities start. It seems to me that it’s impossible to make clear distinctions bewteen different forms of art, they’re rather continuations of each other. So, in the case of my photography, the still lifes against the backdrop, but also the temporary families, I capture in a photo. That means that the still lifes and temporal families might not continue to exist in reality, yet the fact that they are captured prolongs their existence endlessly on the level of the photo. I find that meaningful. Sometimes you see things in an image that you hadn’t seen while you took the photo. When I took that first image of the table, I hadn’t seen how the objects fitted in the pattern – it was the photo that made it visible to me.

View more of Natalia Wiernik’s work on her website.