Sophie Beerens

Terminus

Foil embossed hardback, 24 x 31.5cm, 68 pages

€35

Some eighty miles from Los Angeles, California, at the southwestern edge of the arid and perpetually sunny Mojave Desert, lays the abandoned remnants of George Air Force Base. In 2015, this base gained a new occupant, in the form of renowned visual artist John Divola.

Officially decommissioned in December of 1992 (post-Cold War) the base and adjacent housing complex have since been the host of the sporadic film set, airsoft game, or military training exercise. With the presence of John Divola, however, it became a place of an entirely different kind of operation: armed with his camera and spray paint, through hallways of peeling wallpaper and drywall dust, Divola engaged in a series of site-specific interventions. The documentation of these interventions, are now compiled in Terminus, his latest publication.

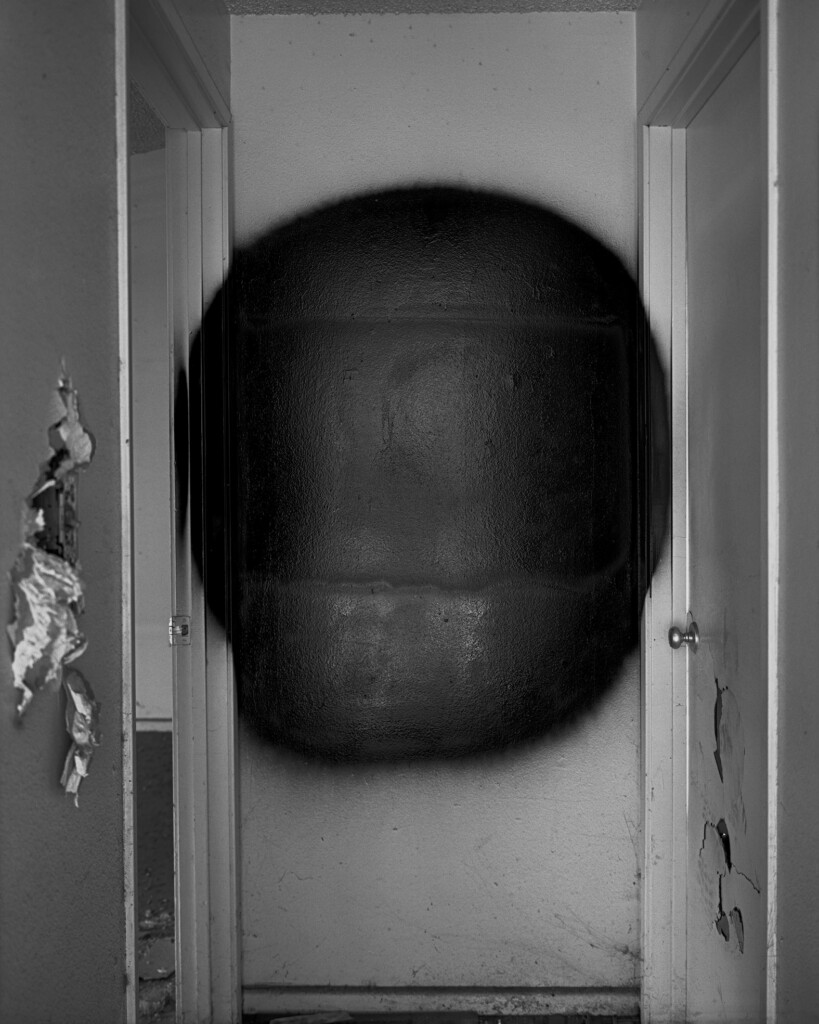

As far as naming goes, Terminus is possibly Divola’s most cryptic. While many of his earlier projects have rather simple, self-explanatory titles, the plurality of meaning behind the word ‘terminus’ makes its connection to Divola’s subject matter rather ambiguous. One can define terminus as the end, or extremity of anything; some impassable boundary, or simply the end station of a railway or bus line. Any definition, however, implies movement, which is perhaps the most central concept of Divola’s project. The spectator moves through hallways as Divola did, witnessing traces of his interaction with the space. The most notable form of this interaction, or intervention, is in the black, spray-painted forms that adorn the ends of each hallway.

“The spectator moves through hallways as Divola did, witnessing traces of his interaction with the space.”

Each photograph could be boiled down to the same essential ingredients: the aforementioned spray-painted form, a hallway, and traces of decay and debris — the photographs never stray from this basic formula. The nuances of each distinct hallway, each with its own level of deterioration, is what sets them apart. Each of these images is marked by the different gestures of different people and individually, the traces of each gesture all present a unique spatial relationship between the camera and the wall, exploring shifting, varying scales and positioning. Each spray-painted form is different, too: some are smooth circles, like black suns burned onto the walls, while others are more abstract, monolithic forms; each shape likewise absorbs and reflects light in completely unique ways.

The forms may have been created with spray-paint, but they certainly don’t conform to any of the aesthetic conventions of graffiti art. There are echoes of the language of abstract expressionism in these painterly marks, which, in itself, echoes elements from his previous projects, specifically the Zuma series (1977 & 1978) and the Vandalism series (1974 & 1975) — although the forms are now far more elementary in nature, and less expressive in their gesture. It nevertheless draws your gaze, and its rudimentary character makes it all the more hypnotizing. There is a sense of obsession as well, in the almost imposing permanence of the many black forms.

“These deserted spaces, free of ownership, invite us tacitly to trespass, and the more forlorn its state, the less qualms we seem to have.”

The George Air Force Base is not the first abandoned place Divola has graffitied. He has long held a fascination for such places, a sentiment shared by many — to the extent that a simple Google search will turn up a term for this very fetish: ruin porn. The internet abounds with archives and blogs of abandoned buildings by country, with instructions on how best to infiltrate without detection. These deserted spaces, free of ownership, invite us tacitly to trespass, and the more forlorn its state, the less qualms we seem to have.

It’s a curiosity that extends back centuries: depictions of ruins took hold in art history during the Renaissance, with ruined buildings appearing in the backgrounds of anatomy etchings, and in countless large, elaborate paintings. When the real ruins weren’t enough, they created imaginary, manipulated fantasies, giving rise to the trend of capriccio. When architect John Soane presented sketches for his design of the Bank of England in 1790, for example, he included one depicting how the building would look as a ruin many centuries later, as testament to the design’s enduring beauty through time.

The aesthetic possibilities of decay and deterioration have been long established, appropriated and stretched — although often admittedly far more extravagantly than those of Divola’s stark, black and white images, which almost read like absurd takes on real estate listing photography.

The precise history of the abandoned places Divola occupies, however, is rarely his main concern. There’s something to be said about the historical significance of military bases such as the one featured in this project, George Air Force Base. Like many others of its kind, it is now a superfund site — a polluted location that requires a long-term effort in cleaning up hazardous contamination. There are currently more than one hundred of these sites in California alone — of which at least 14 are connected to the military, remnants of the almost frantic militarization of the desert West brought about by the onset of the Cold War. For Divola, however, this history is but one of the countless gestures that has shaped these remnants — layer upon layer of engagements. Divola has now added a gesture of his own, in the form of these photographs — each one an artifact, inseparable from the whole.

“What enduringly unifies Divola’s bodies of work over decades is that his processes, movements and engagements have always been inescapable aspects of his photographic content.”

One could see Divola’s site-specific gestures as a return to the primeval forms of artistic output. Whereas the modern art piece has an often nomadic existence, moving from home to gallery, gallery to museum, and has thus attained more autonomy, Divola’s gestural manifestations echo that of the primitive cave painting, or the church fresco: fixed in its positioning, and drawing the audience toward it. In fact, the word graffiti, from the Italian word graffiato, meaning scratched, once referred to the ancient inscriptions and figure drawings — now most likely revered and valorized as priceless artefacts — etched upon the walls of tombs and sepulchres, rather than the flat, spray painted designs now synonymous with the word. It is the surface on which one finds the work that provides its essential dimensionality and body. The core of each form, however different in its methods and output, is the same: it is a work of the public domain, eschewing the constraints of the capitalistic institutions that now house much of the world’s most prized artistic artefacts.

Divola recalls, in his days as a student in 1970’s Los Angeles, seeing a majority of art through its photographic reproductions; indeed, the typical art student will most likely see more art in photographic reproductions than in the flesh. It was through this convention — of seeing art in the final form of the photograph — that Divola came to believe that all art was, in a sense, fabricated to be photographed. Photography as a momentous bridging of all forms of art, into this artifact that redefined aspects of distance and time. And while the photographic tradition of the time, especially within the Los Angeles scene to which Divola was exposed, was experiencing a renewed valorization of the “non-intervention” of the subject — that is, a complete departure from any excessive subjectivity with regards to the photographer’s role, Divola’s work marks a distinct rebellion against this.

What enduringly unifies Divola’s bodies of work over decades is that his processes, movements and engagements have always been inescapable aspects of his photographic content. The archive is, and has always been, his main enterprise — a record of his movements, and the places he has activated through his varied interventions. In the final image of Terminus, we see, reflected against the sheen of the black spray paint, the ghostly form of Divola himself. It’s a definitive, indelible mark of his presence, not only within the abandoned base, but within his own archive, and within the extended universe of his works.

If there’s anything beyond curiosity, or wonder, that draws us into abandoned spaces, it’s perhaps a soft, small hope to bring life back into its vacuum. To reactivate its being, to gift it new memory, and to welcome gesture back into its stillness. Terminus may suggest a sense of finality in its naming, but the artist’s thirst to mark his mortal presence on these places of abandonment, is a gesture of enduring spirit.

John Divola (1949) is a visual artist and educator living and working in Riverside, California. While he often refers to himself as a photographer for convenience, Divola’s work often explores the intersectionality of photographic practices with other diverse forms of visual art. His body of work, spanning 5 decades, can be explored on his website, which takes the form of an extensive online archive. The works of Terminus are but one of a number of projects taking place at the George Air Force Base. His latest publication, Terminus, is available at MACK Books, an independent publishing house based in London, UK.