GUP TEAM

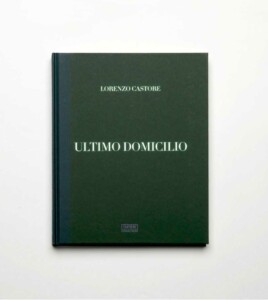

Ultimo Domicilio

Hardcover / 108 pages / 245 x 305 mm

€ 45

Going to someone else’s place for the first time is always intriguing. Houses are the containers of our obsessions and of our prosaic moments, they’re the places where love, death, sorrow and joy occur among our cups, wardrobes, bookshelves, sofas. They all witness our intimacy, and the act of observing someone else’s house is (at least for me) fascinating.

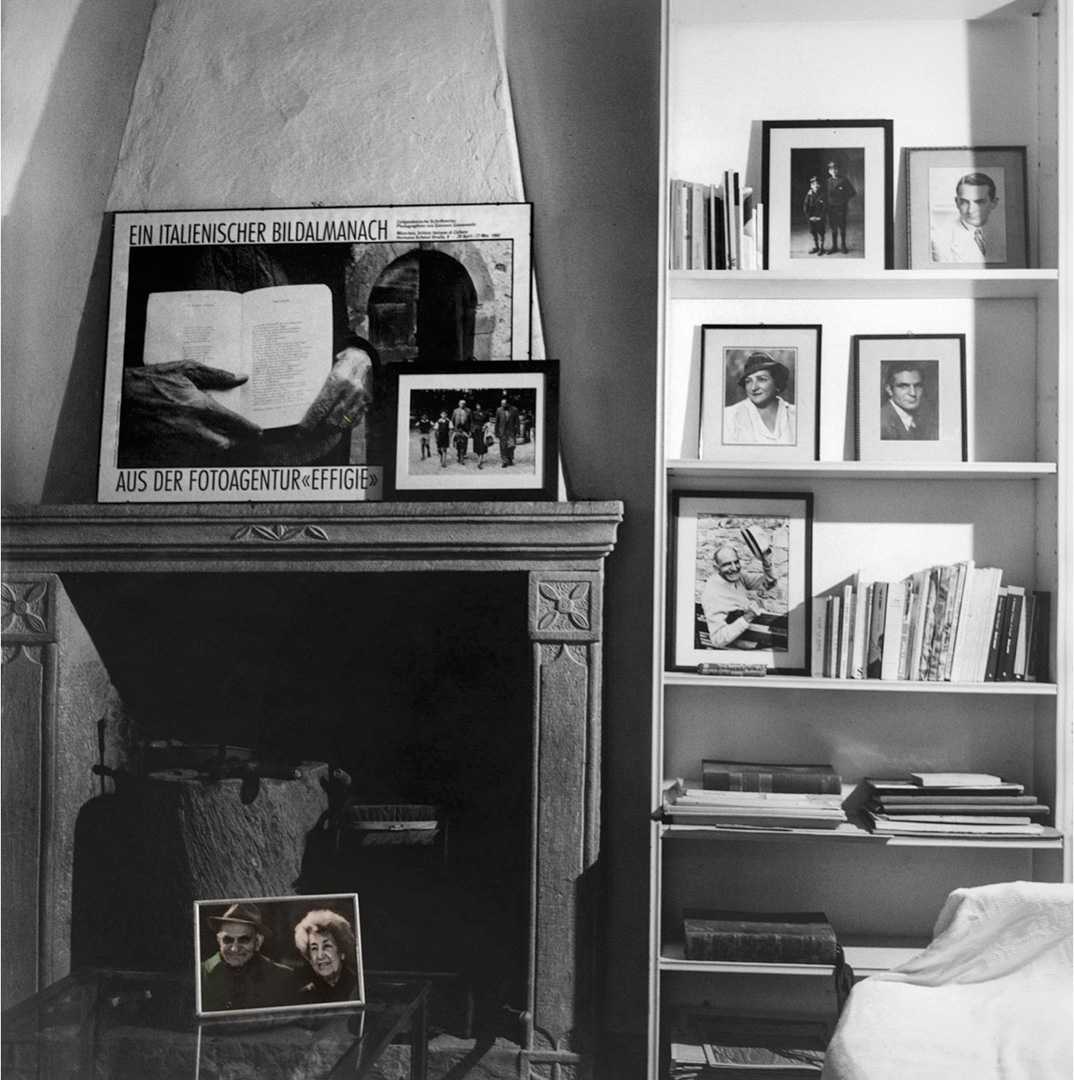

For his book Ultimo Domicilio (meaning, Last House), Lorenzo Castore (b. 1973, Italy), photographed seven houses with which he had been acquainted or just fascinated for a long time, presenting extremely diverse environments: an Italian 16th century palazzo, a grandparents’ flat in Florence, a house that met the war in Sarajevo, and three artists’ homes, in Italy, France and Brooklyn. The last portrayed home is (or was) Castore’s own flat. Some of these places have ceased to exist as we know them in the book, as their inhabitants died or had to move out.

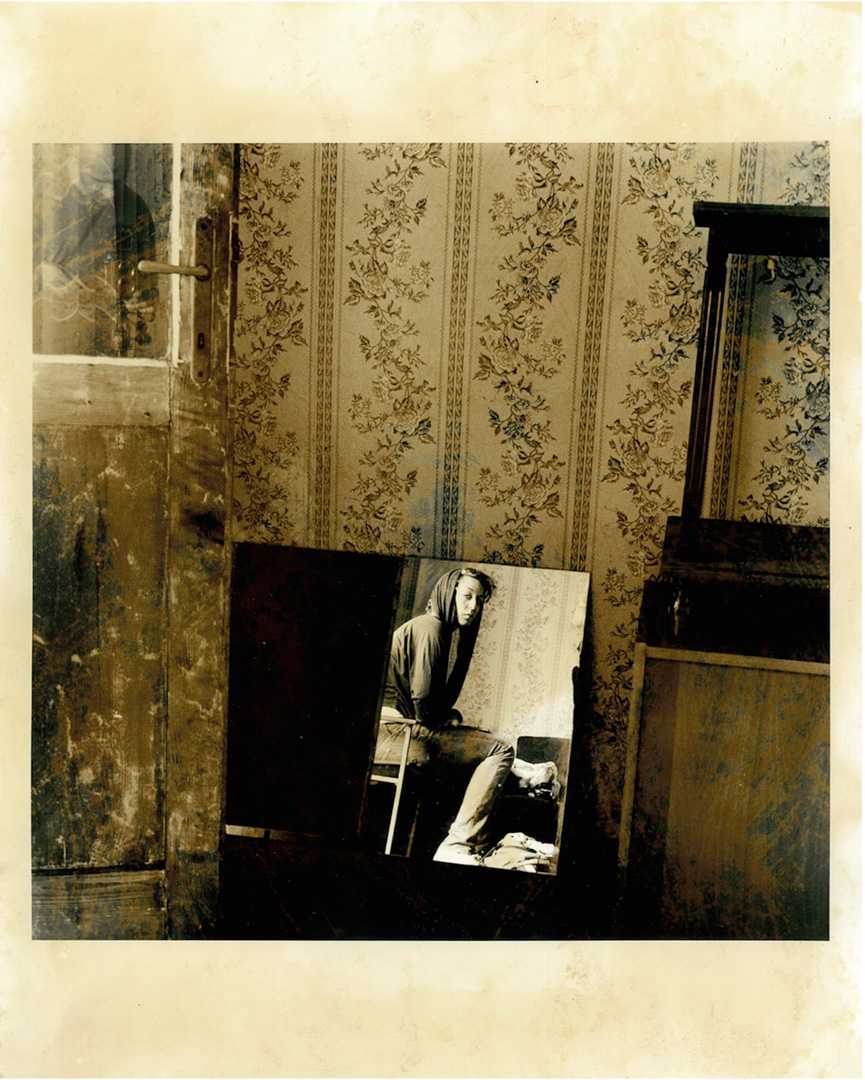

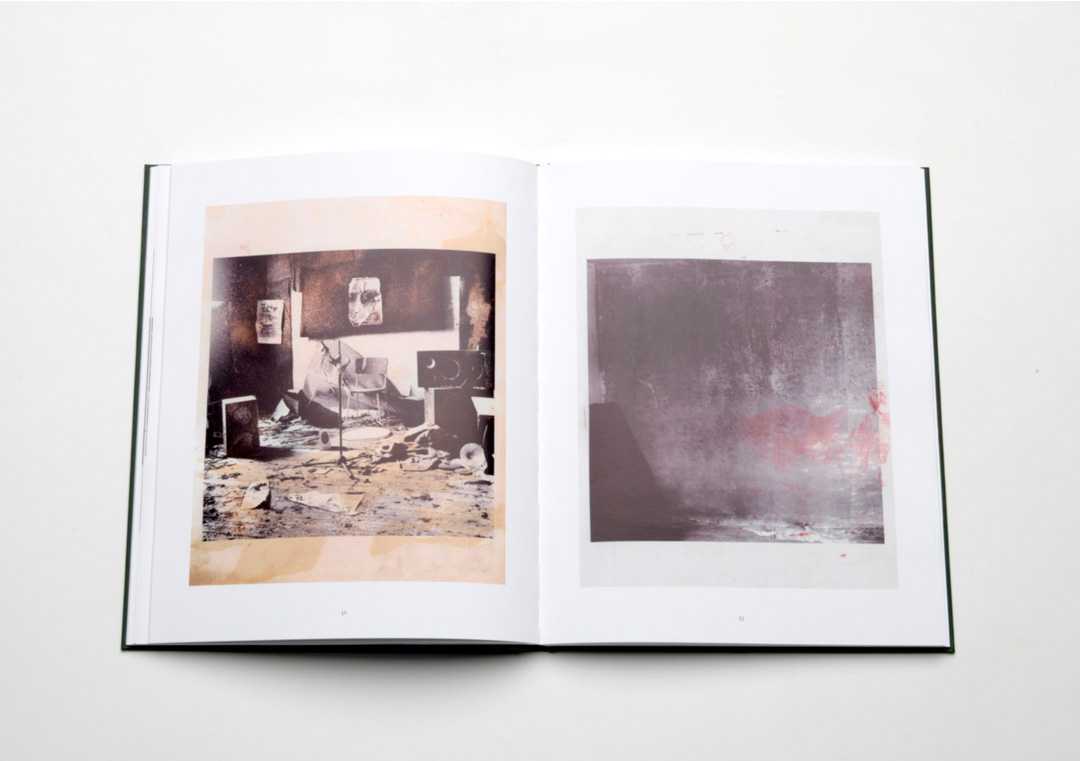

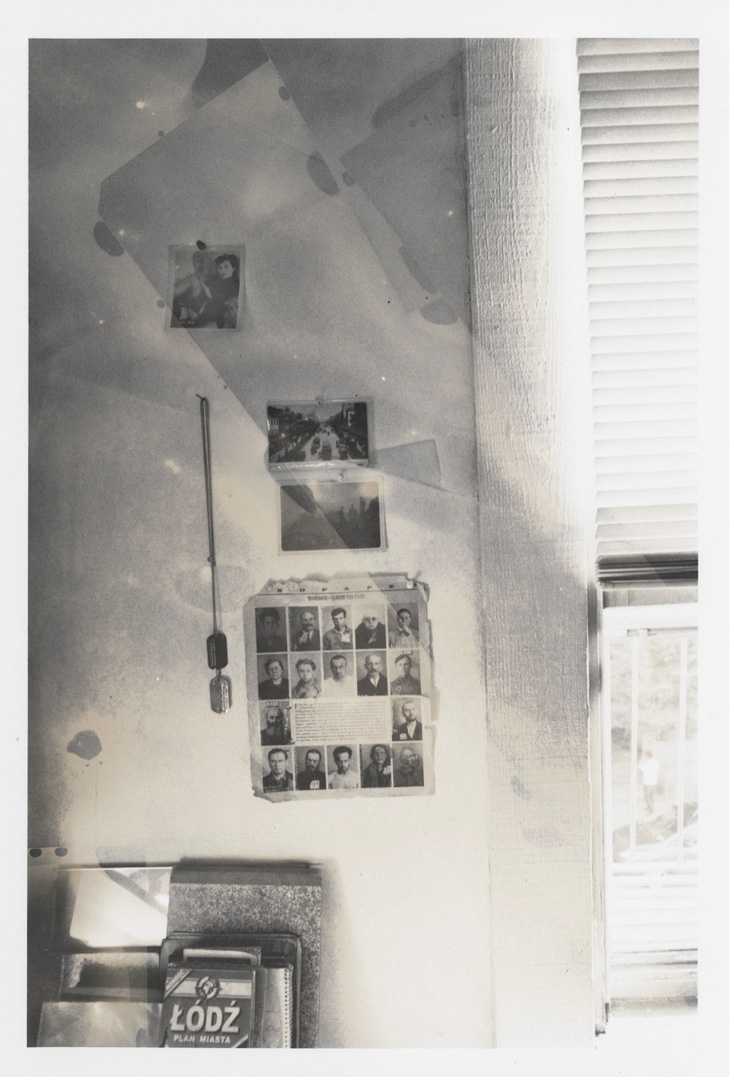

Castore has used different formats and techniques to portray these places: it feels as if each of them had instructed the photographer how he should approach them. He takes a very direct way of photographing, and according to the different feelings that each environment evoked in him, he was able to achieve photographs embedded with his own presence and attitude towards that space, and the houses’ distinctive genius loci, their own spirit. For each of the domestic locations, Castore either shows off the house’s oddities, the inhabitant’s fetish for particular objects, or just how the space used to be. In some cases, he intervenes directly on the pictures: the photographs of the Bertolucci family house are treated in a way that only certain colours emerge, like ancient coloured postcards evoking the most delicate feelings, while the photographs taken in Sarajevo look like they have been burned, or left for years in an abandoned and derelict space in the aftermath, in a clear reference of the war experience.

Far from being relegated to take a voyeuristic role, the viewer is invited instead to be part of the illusion that photography can preserve everything forever. As viewers we are somehow kept at a distance: we won’t be initiated to the houses’ secrets and, in a way, we’re not really invited to come in. This book is about Castore’s own love story with these houses, the constant roaming among them, and the act of photographing their interiors was probably not only a quest to preserve what was left, but rather an exploration of his own possible lives. Castore is a pilgrim looking for himself through these houses, drawing from their inspirational potential. With his awareness of the transient, he has photographed much through the lenses of respect and curiosity for the inhabitants of these places. In the afterword, he shares a few elements about the history of each house.

A last remarkable detail is Castore’s approach in photographing what used to be his own home in Krakow: the photographer is detached, with the attitude of someone who tries to observe himself from the outside, with a slight hint of narcissism. We see the walls exclusively decorated with early 20thcentury family portraits and erotic images from the same time. The book ends with a photograph showing a red suitcase in an empty space, and perhaps it shows Castore’s last look to the house, before closing the door forever.