Xu Guanyu (b.1993, China) is a Chicago-based artist. For his project ‘Temporarily Censored Home’, he returned to his parents’ residency in China where he grew up as a teenager prior to emigrating to the United States. He was born and raised in a conservative family in Beijing, where non-heteronormative behaviour is a taboo. Due to these circumstances, Xu never came out to his parents as gay.

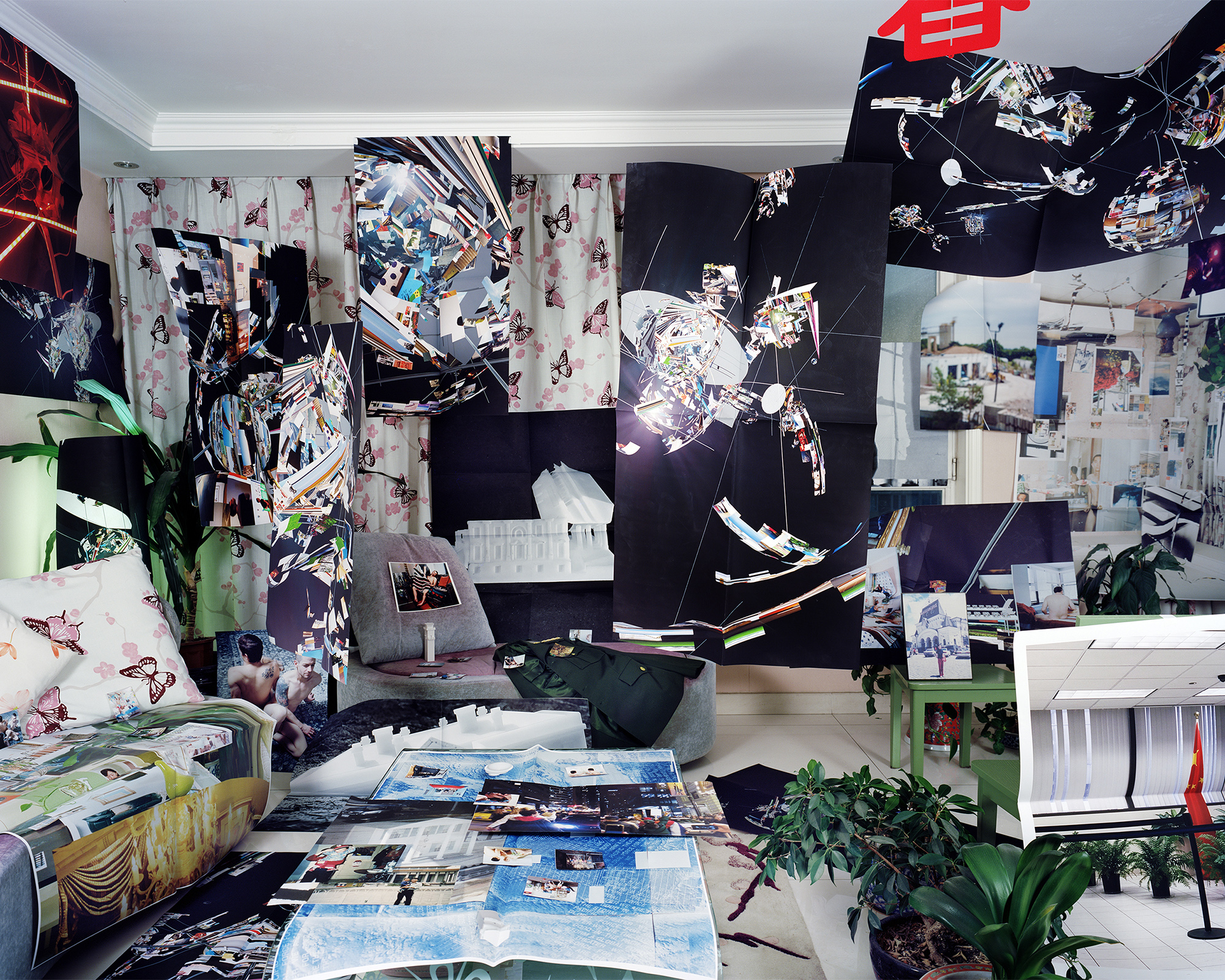

In the series, Xu creates temporary installations in order to queer the normativity of his parents’ heterosexual space. The images comprising the installations are from his other project ‘One Land to Another’ that portrays him and other gay men in their domestic settings. Additionally, they include photographs of landscapes, built environment in the USA, Europe and China, torn pages from fashion magazines that he collected as a teenager and lastly, images from his family photo albums. Through these fleeting displays, Xu reclaims his home in Beijing as “a queer space of freedom and temporary protest.”

In an interview with GUP, and in the context of his show during BredaPhoto 2020, Xu talks about the creation process of ‘Temporarily Censored Home’ and reflects on his experiences with LGBTQ oppression.

Your project was originally inspired by Sara Ahmed’s book ‘Queer Phenomenology’, concerned with how social relations are arranged spatially where queerness is disrupting such relations. How did you translate her theories visually in ‘Temporarily Censored Home’?

In the project, I’m constantly reflecting on my past experiences in these rooms, especially my relationship with objects, symbols, and aesthetics within the space. I re-arrange objects and juxtapose them with my images. For instance, in one image you could see the statue of Mao that is looking at my suitcase with prints. In another image, you will see my father’s military combat gloves lurking in a drawer. Moreover, the layered images in these installations also obscure, confuse and slant the space. These juxtapositions, contradictions, and disruptions are conjuring my past as well as open up space for a potential future.

‘Temporarily Censored Home’ installations were created in your parents’ home in Beijing. They could only exist temporarily as whenever your parents were approaching home, they had to be taken down so that your sexual identity is not revealed to them. Meaning, they have remained in the dark about all this. Will you at some point come out and show the work to them?

I’m currently undecided towards such exposure. But for some reason, I feel they will find out soon. They already discovered that I had a show at Yancey Richardson Gallery recently. But due to the compressed images they saw on Chinese media, they still don’t know what exactly is presented in these images. This September I will have a solo show in Shanghai. So, it feels even more close… It’s an unfolding story.

The installations can be said to mirror the process of your identity formation throughout many years and across different spaces and cultures. Was this something aesthetically challenging to visualize?

Thank you for this question. I think I want to keep each image different and open-ended. The photographs deal with different parts of my past and present. For instance, in ‘The Dining Room’, you will see protest photos (the first protest I ever been to) of the night after Trump’s election as well as my photo of Wolfgang Tillmans’ anti-Brexit posters in Brussels. On the other hand, in ‘Reanimated Bedroom’, you see everything is revolving around a computer-generated image of my bedroom but filled with my mom’s images that she took in the US and Europe. They represent different aspects of my identity.

In many ways, it’s not difficult to visualize because it will change constantly anyway. So, what I did was to push myself when I was making them and eventually accept the open ending.

As experiencing both, how do you reflect on the different types of LGBTQ oppression in China and the USA? And how do they resonate in your project?

Racism, sexism, and anti-LGBTQ sentiments have increased since Donald Trump’s neo-nationalist election and his belligerent governance. Growing up in China, my education was embedded within a deep nationalistic ideology. This comparison between the U.S. and Chinese policies reveals a simultaneous operation of nationalism and imperialism as a means of centralizing power. These male narratives of power connect and dominate individuals and institutions, private and public, personal and global.

That is to say, the normative views toward marginalized groups are more or less similar in both countries: a dominant norm marginalizes many people who are different. In China, if you are brave enough to come out, there are many people who actually accept it and there are lesser incidents of hateful speech and action. Of course, there is no law to protect, and the cultural product will be censored. On the other hand, in the US, if you do not fit in the homonormativity, there will be countless obstacles one has to confront just within the gay community itself.

One of the reasons I made this project is to express my powerlessness and the struggle between the two countries. That means not only the inability to be myself but also my political view that is caught between the two. I think it’s more and more clear this year.

“(…) it will change constantly anyway.”

“(…) the normative views toward marginalized groups are more or less similar in both countries.”

What are you working on at the moment?

Like many emerging artists and resident aliens in the US, I’m figuring out life during COVID-19. Recently, I received my artist visa, which cost a great amount of money. I’m planning my first solo show in Shanghai this September. I will show my project ‘Temporarily Censored Home’, ‘Complex Formation’, and a new computer-generated image once I pass the censorship. As a teaching artist, I also need to plan on teaching online in the next academic year if my school will accept my current visa. There are many uncertainties…

Xu Guanyu won the Lenscratch Student Prize and FOAM Talent in 2019. GUP is media partner with BredaPhoto2020 and Xu’s work is to be featured in context of “China Imagined”, a major overview of Chinese contemporary photography co-curated by Ruben Ludgren and He Yining.