ANTHONY GUEVARA

Dutch photographer Eddo Hartmann (b. 1973) visited North Korea four times between 2014 and 2017 to produce the images for the exhibition Setting the Stage: Pyongyang, North Korea—a series for which he recently won first place in the 2018 LensCulture Exposure Awards. The series and exhibition, which is on display at the Huis Marseille in Amsterdam, is a captivating and eerie look into perhaps the most secretive country in the world.

The series begins with scenes of deserted store fronts and kiosks, scenes that are ostensibly devoid of people. However, looking closer you can make out certain tell-tale signs of life: the concrete in front of a kiosk is clearly depressed in two lines where thousands of people have queued over time; where a massive, spherical exposition centre dominates the image, two people are riding a single bike at the edge of the frame.

In a country where the leaders are gods, it is the people that are in the details.

Typically, the photographs coming out of North Korea are reportage in style, but thanks in large part to him working with a slower medium format camera, Hartmann’s images have a more measured, formal quality to them. It is here that the large prints on show at the Huis Marseille really come to shine, his choice of format offering plenty of details to get lost in.

For Hartmann, this aesthetic was a conscious departure, as it was a way to not only differentiate his work from that of other photographers who have worked in the country, but also to gain access to the hermit nation—something which is not easy for Western journalists. Working through a Beijing-based production company, he proposed a unique project:

“Let’s use the public space to tell something about the country, purely starting with the architecture. So I told them. ‘Show me the city as you want to show it.’ They found it an interesting new angle instead of going through the standard street photography which everybody does,” he notes.

“This was my Trojan horse in a way.”

And in the beginning his photographs featured mainly buildings and public spaces, but slowly—both during his visits to the country and in the exhibition where this process is mirrored—people started to enter the frame more and more.

But photographing what he wanted to was not easy with two or three “guides” constantly minding his every move and peeking over his shoulder at the screen of his camera, demanding that images be deleted if they didn’t conform to regulations. This obviously raises the question of whether images produced under such strict guidelines are nothing more than propaganda from a nation that could be described as having a PR-problem internationally.

Hartmann is conscious and very open about the potential for controversy in his work: “Sometimes you get comments like, ‘Where are the poor people? You cannot show anything from North Korea as long as no concentration camps are shown.’ We know this story, we know that they’re around. The reports of Amnesty International don’t lie. It’s very, very clear. But what use would it be to constantly focus on this part? They say: ‘Yeah you only take pictures in Pyongyang, that’s only for the Elite so it doesn’t say anything.’ We know this. It’s like if you go to New York, it isn’t the U.S.”

“I really like [those kinds of discussions],” he professes, “because then you’re really on top of the story.”

Even the title of the series and the accompanying book, Setting the Stage, suggests a consciousness of the artificial nature of Pyongyang—especially of what is shown to foreigners. For example, visitors to North Korea are not allowed to enter the homes of North Koreans, but instead are shown a staged version of what the house of an average citizen is supposed to look like.

A bedroom from this make-believe home is featured in Hartmann’s series, but he cheekily angled his camera to show that the room has no ceiling, instead revealing what look like the dark structures of a movie set. “You have this really facade-like feel to Pyongyang, and just beyond that first row of buildings, there’s another kind of view: a much different world.”

In 2015, Hartmann had an exhibition in Pyongyang where he showcased images from the current series, becoming the first Western photographer to have an exhibition in North Korea. “It was very strange,” he says. But he was also given the chance to exhibit some of his previous work from Europe, which raised the question of what to show: happy people in rich environments? “That would be very cheesy and stupid.”

In North Korea, art in general is very literal and its purpose is to serve the revolutionary regime and its message, while photography in particular is seen as something very functional, not a medium for personal expression. Echoing CIA programmes to promote notions of freedom and self expression by financially supporting the early Abstract Expressionists in the first decades of the Cold War, Hartmann chose to display images of abstract architecture. “To make something abstract would in their eyes be completely wacko, because what’s the use of having a picture that only consists of lines?”

During the exhibition in Pyongyang, many North Korean patrons confronted him with this question. To them he tried to explain his use of unusual angles and non-literal subject matter, which wasn’t always successful. “So that was my way of being kind of subversive, just by showing abstract art.”

A big question for Hartmann is how to convey his experience in a country most people will never get a chance to visit? The experience of Pyongyang that he shows us in the current exhibition is one where life is so organised that even the distances between people seem to be regulated, where buildings and public spaces are not built to human-scale, but rather for history: the streets are immensely wide in order to host military parades,the monuments enormous to celebrate the revolution and its leaders.

The amount of empty space without a car in sight creates an eerie atmosphere, like a movie set in-between productions, and this is accentuated by a ghostly sound that grows louder as you move through the exhibition rooms at the Huis Marseille. This is the recording Hartmann made of a “revolutionary opera:” a voiceless, otherworldly piece of ambient that blares every morning and evening out of countless speakers situated everywhere in the city. It is a chilling cacophony, more reminiscent of David Lynch than communist kitsch.

The exhibition culminates at the top floor of the museum in an immersive 360-degree experience from the Pyongyang metro, complete with headphones and VR-glasses. It is a mesmerising experience to stand in one of the metro carriages with its local passengers, or gaze at the commuters walking by in one of the splendid stations inspired by the Moscow metro.

“What the main thing for me is to realise that there are 25 million people living there that just make the best of it, you know? They’re not a bunch of zombies walking around: they also have marriages, they fall in love, they’re worried about getting their kids to school. After seeing the 360 video, somebody said to me ‘They just look like people!’ Well what did you think?”

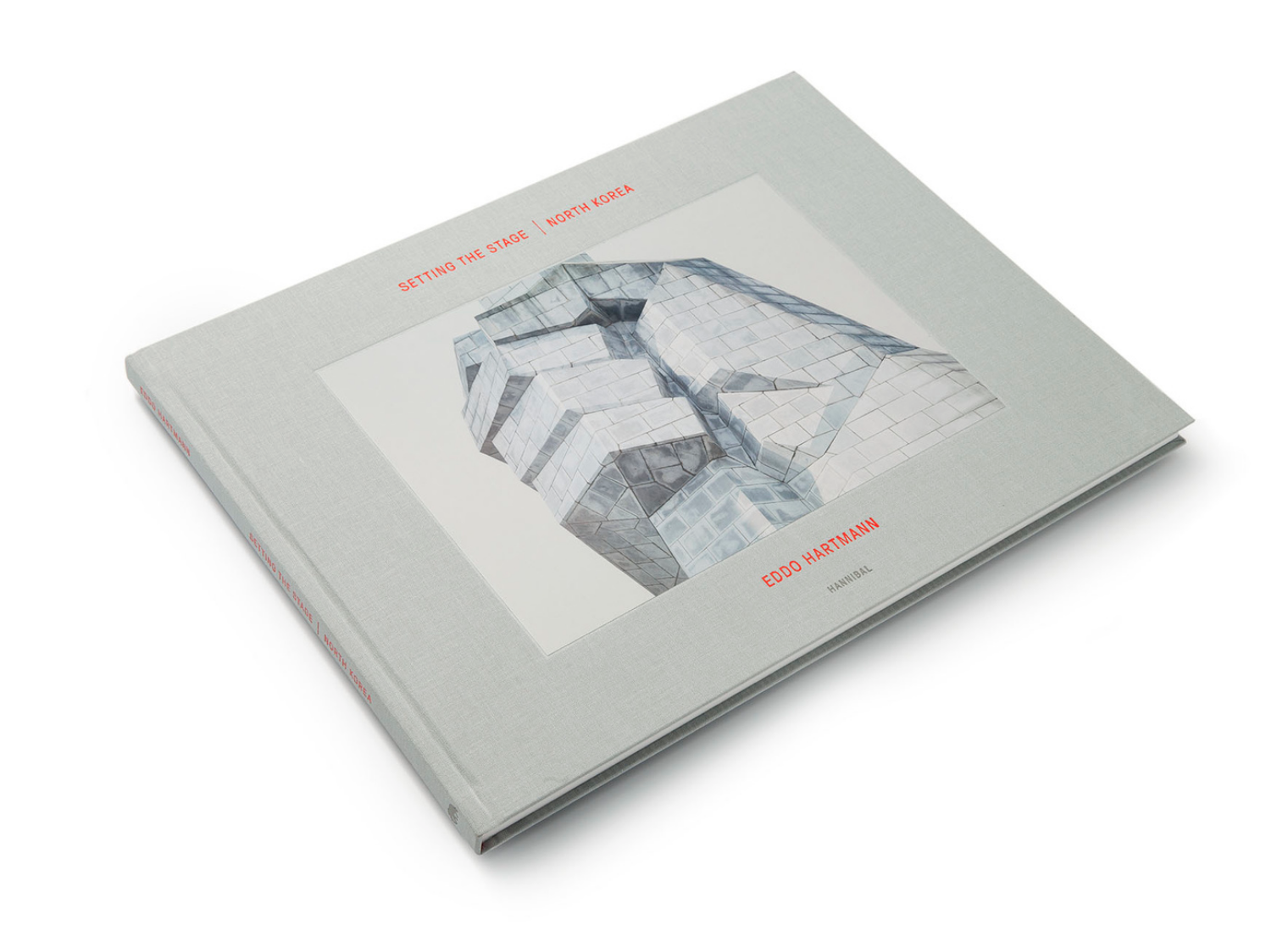

Eddo Hartmann’s exhibition Setting the Stage: Pyongyang, North Korea, Part 2 is open until March 4th, 2018 at the Huis Marseille, Museum for Photography in Amsterdam and the accompanying book was published by Hannibal Publishing in 2017.