Leonard Suryajaya (b. 1988), a Chinese-Indonesian artist living in Chicago, had to face the American authorities and their cynical questioning regarding his immigration. His project False Idol reflects the process surrounding the course of his Green Card application – a rather estranging experience.

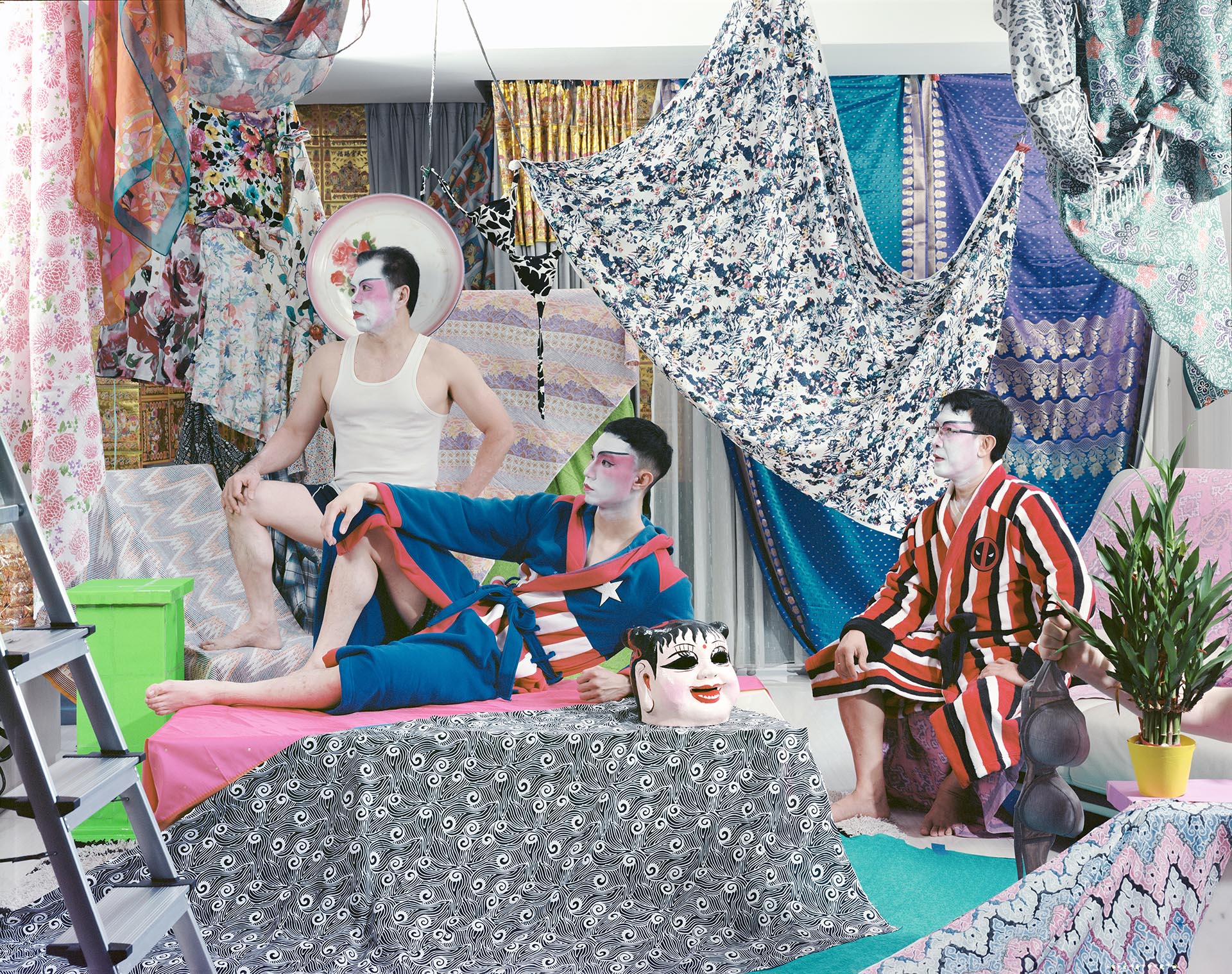

Floral printed sheets, strange plastic objects, an abundance of fruit and vegetables, an explosion of colours and patterns; Suryajaya’s imagery is “queer”, providing a keen perspective on what it means to diverge from cultural norms. The subjects posing in these scenes are mainly relatives, who clearly trust the man behind the camera. The work also includes collages that intersect imagery with text, and a video interview with Suryajaya’s mom. In all, False Idols is intriguing and triggers a lot of questions.

Your personal experience of applying for a Green Card was what initially started the project. Can you elaborate on that process?

I spent ten years in the United States on a student visa. When it expired, I decided to pursue permanent resident status, also known as Green Card, to guarantee my stay in America. In order to do this, I married my partner in 2016, a few months after gay marriage became legal in the US. The application process was tedious and demanding. Not only did I have to prove my love and allegiance to my spouse, but I also had to document my work and worth to prove that I could support myself and that I wouldn’t be taking advantage of birth-American privileges.

The Green Card process represents a very hetero-normative and rigid system, defining “love” and “family” in very narrow and neat boxes. It felt extremely hard and deplorable submitting myself to the government. Mind you, I had applied to stay in America when Obama was president. When I transferred from a student visa to a temporary Green Card, my new work permit – which should have overlapped with the old one – arrived late, and it resulted in my termination from my teaching job. It was heart-breaking. I was hoping to use my employment as a teacher to vouch for my Green Card application. But it seemed like America didn’t want me to immigrate as a teacher. So, I took the challenge of applying as an artist instead and created a corresponding body of work.

“When inspiration presented itself to me, I just tried to pursue it”

Did the way you visualise the key points of this experience differ significantly from how you approached previous projects?

False Idol is a culmination of my artistic approach to making work, and it’s more ambitious than anything I had worked on before.

It felt very dehumanising to have to prove my livelihood and values to the US government in order to feel a sense of belonging. The Green Card process revealed traumas I never dealt with growing up in Indonesia as a persecuted minority. Most of the time, facing the uncertainties, I felt on edge, unsupported and unsafe.

But when inspiration presented itself to me, I just tried to pursue it. These moments were the distraction I needed from thoughts of death. What you see in my work are these glimpses of creativity and my commitment to life in the face of adversity. It is a pledge to happiness, in the midst of chaos. False Idol is my way of reconciling these conflicts and of showing my excellence.

In False Idol, it is primarily your family members posing for you. Were they keen to be involved from the start?

I’ve been photographing my family since I was in school. They have always been supportive of me and willing to participate because they wanted me to get an “A” in my photo projects. I must say that they were nicer to work with in the beginning, when the whole photographic endeavour was still a mystery to them. Now, they are so sassy! My mom will still go out of her way to assist me in setting up, moving things etc. My dad and sister are a duo diva. They only want to be called in when I’ve already set everything up.

Your imagery presents an overabundance of objects, symbols and patterns, which resemble intricate theatre sets. Is there some kind of (art-)historical reference to the specific use of these “tableaux”? What is the significance of the theatrical settings?

Actually, I have a degree in Theatre too. To me, the photo frame is a stage. My task is to fill it. With my people, my dreams, my questions, my humour, my fears and anxieties. I enlist my loved ones and my community as actors in these images and I use props, patterns, colours, poses and gestures to signify the time and space that we occupy.

Simply put: why be basic when we can be extravagant?

As a queer kid growing up in a conservative setting, my fears and anxieties convinced me that I had limited time with my family. I aim to remember as much as possible: where I came from, where I grew up, the people I care for. I always wanted to be close to my relatives, but while still being in the closet, I was so convinced that they would shun me, disown me and throw me out when they found out.

I didn’t know at the time how to share my love for them with words, or even with physical affection. But now, I just want to celebrate every minute I have with my family as if it is our last meeting, and to make these wonderful photos as a gift to myself and to them.

“Why be basic when we can be extravagant?”

At first, your photographs appear chaotic but there is a sense of harmony too. What role does a balance between order and confusion play in your visual language?

As a minority in my home country and in the US, as a queer millennial looking for a safe space to call home, I possess an awfully specific perspective. Making art is my access to feeling powerful and free. Despite the adversities and limitations that I’ve faced, it is me experiencing the utmost autonomy over my own existence, my potential and my excellence and aspirations.

I’ll turn 32 this year, and I know that Utopia isn’t going to happen in my lifetime. It sucks, but I won’t be sour about it. What I can do is find moments of celebration and harmony amid all the misery and disorder. I acknowledge the hardships, but I refuse to be defined by them.

In the end, I hope that the work I produce can serve as a reminder that being responsible and compassionate is more important than being right.