ALEX BLANCO

Combinations of seemingly unrelated images, handmade collages, striking colours and use of flash make the images of Ukrainian photographers Elena Subach and Viacheslav Poliakov very attractive and almost exotic to the Western audience. However, the citizens of their motherland might never be able to understand the works of the duo in depth. According to Poliakov, “at home, we are perceived as a mockery”.

The Ukrainian audience is still adjusting their taste to colourful pictures raising questions of life and death, or the loss of creativity, in these times of digital distraction. Meanwhile, Western European countries approach this Eastern visual language with pleasure and curiosity. GUP spoke to Subach and Poliakov about their oeuvre, new projects, inspiration and about art as a socio-political tool.

Tell us how you two met and decided to create a photographic duo.

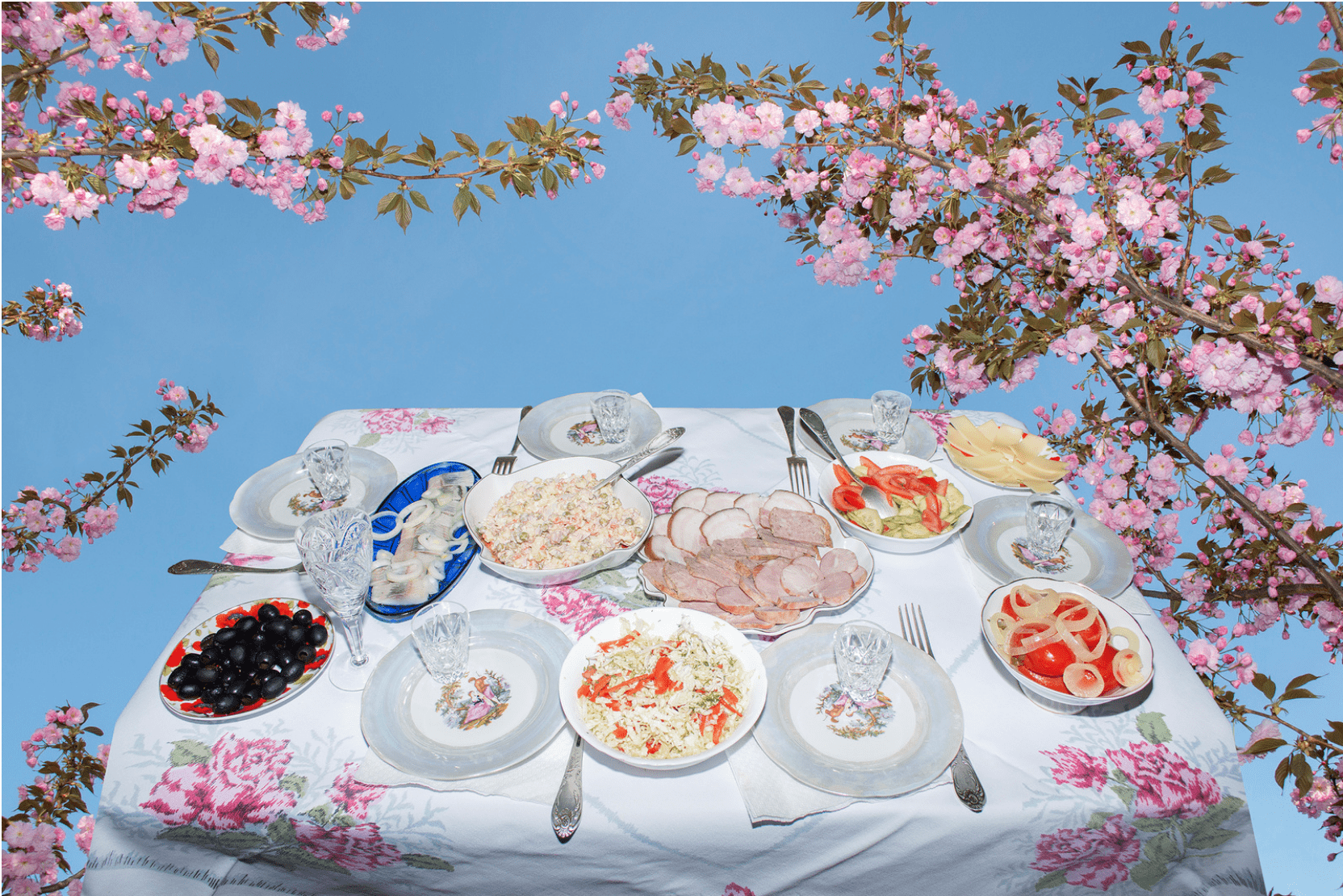

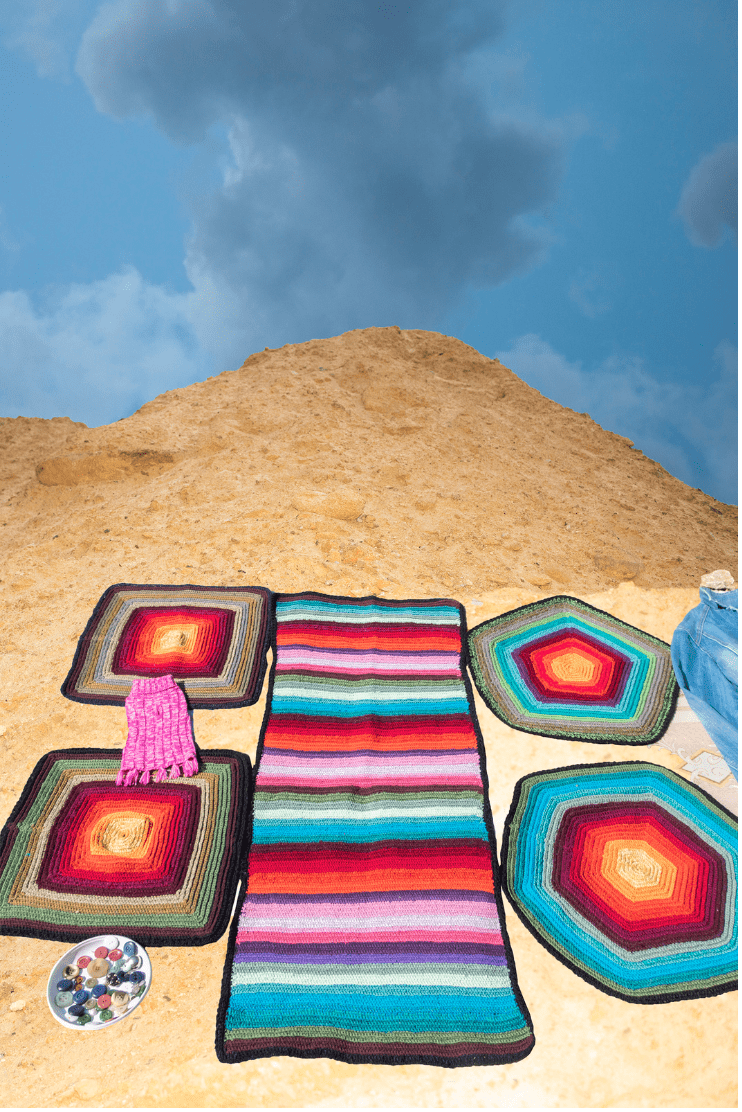

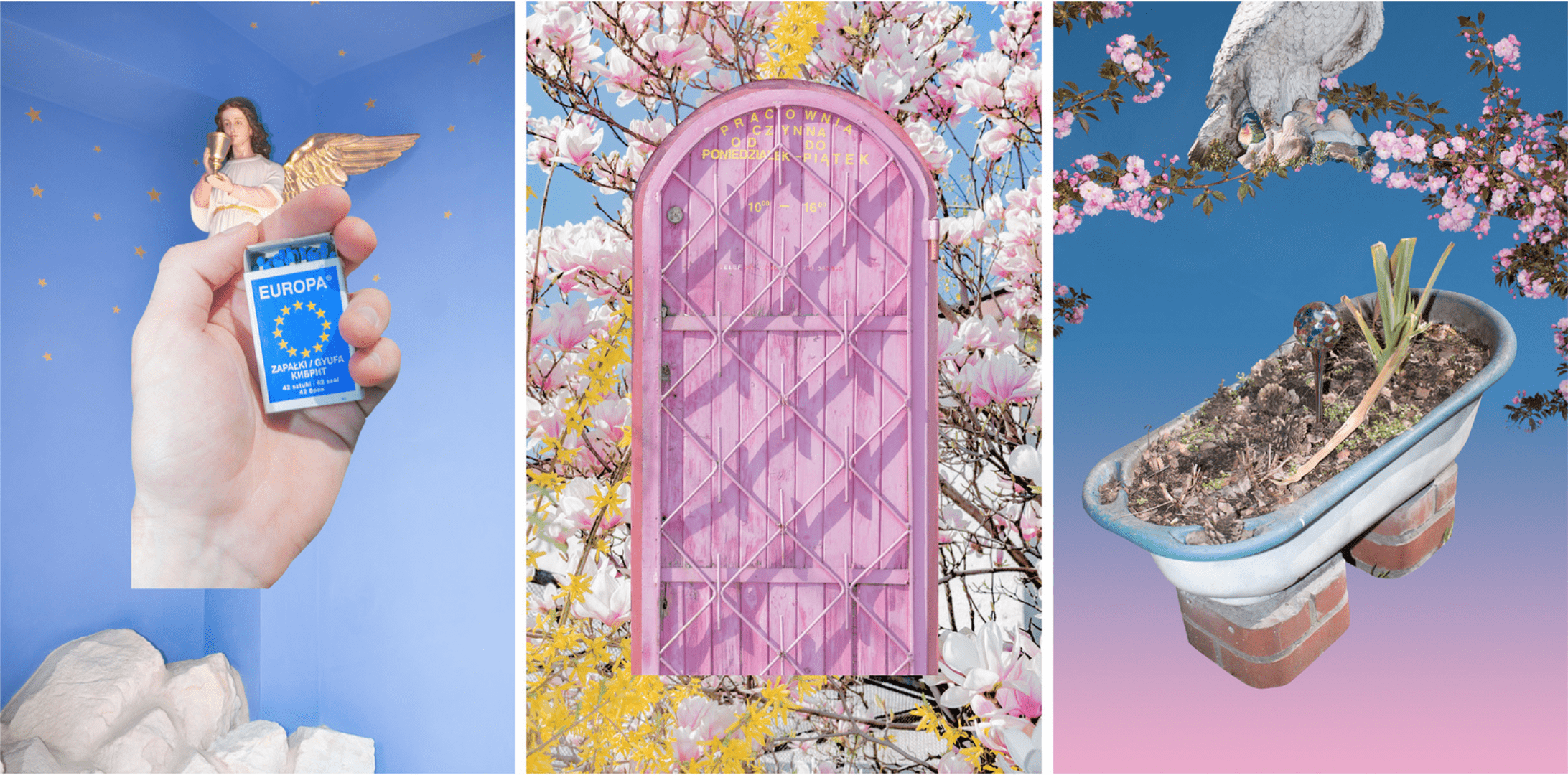

Elena Subach: We met around 6 years ago in a photo club in Lviv while searching for a photographic community in a new city. During that time, just with a camera in hands, we would walk long distances in search of peculiarities in dusty endangered Ukrainian villages. Regarding the collaboration, it all began with these small trips across our motherland. We started creating separate photographic series in the same locations and later on, continued with helping each other with photo selections and constructive criticism. City of Gardens was our very first collaboration. It was a matter of combining the photographed material for collages, the decision on the narrative and the style and… ‘voila!’, the project was born.

Tell us a little about the process of photographing your project Grandmothers On the Edge Of the Heaven. Where did you find the grandmothers and how did they react to the camera?

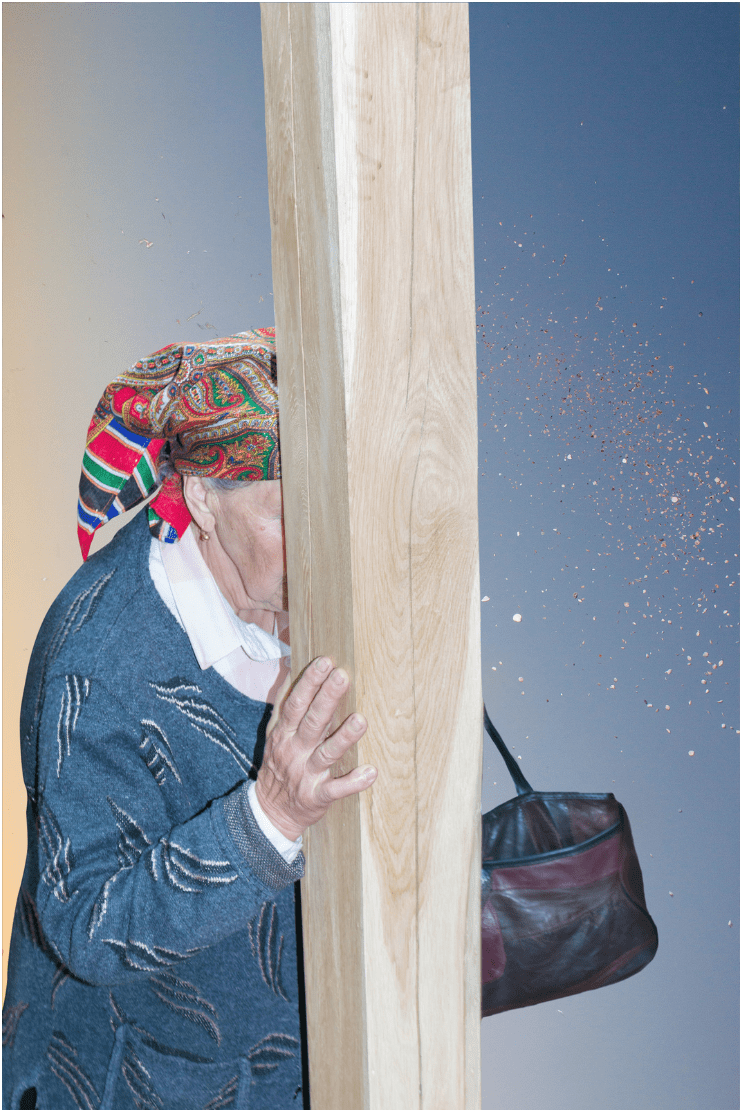

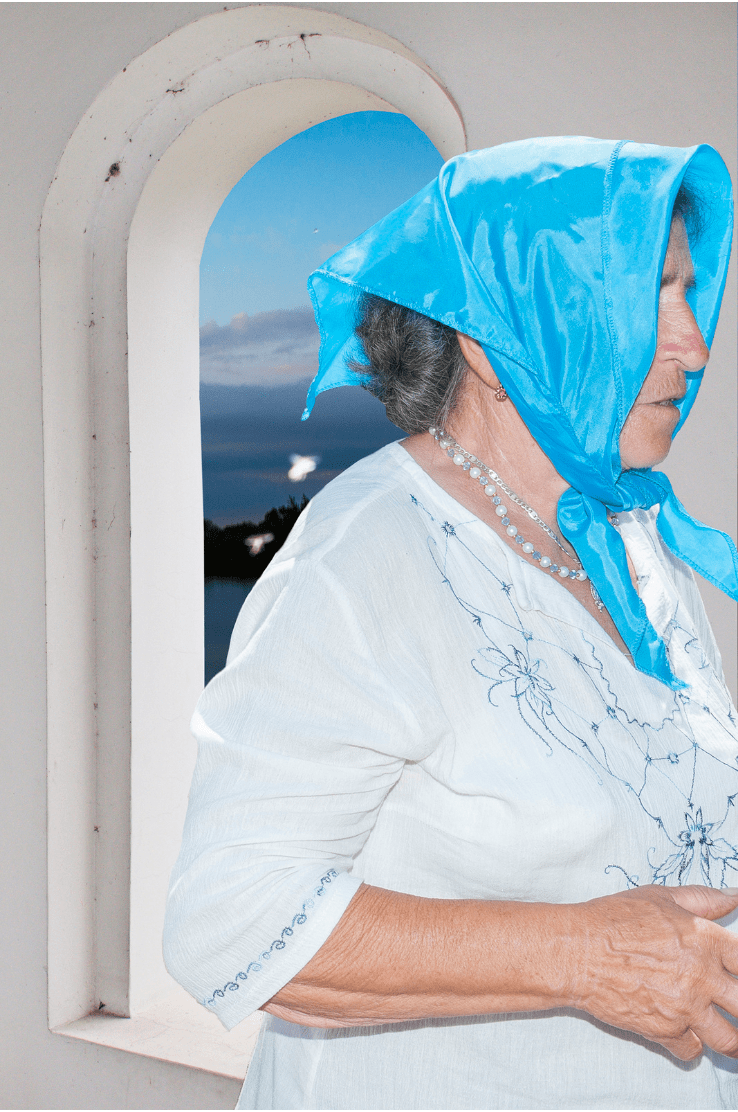

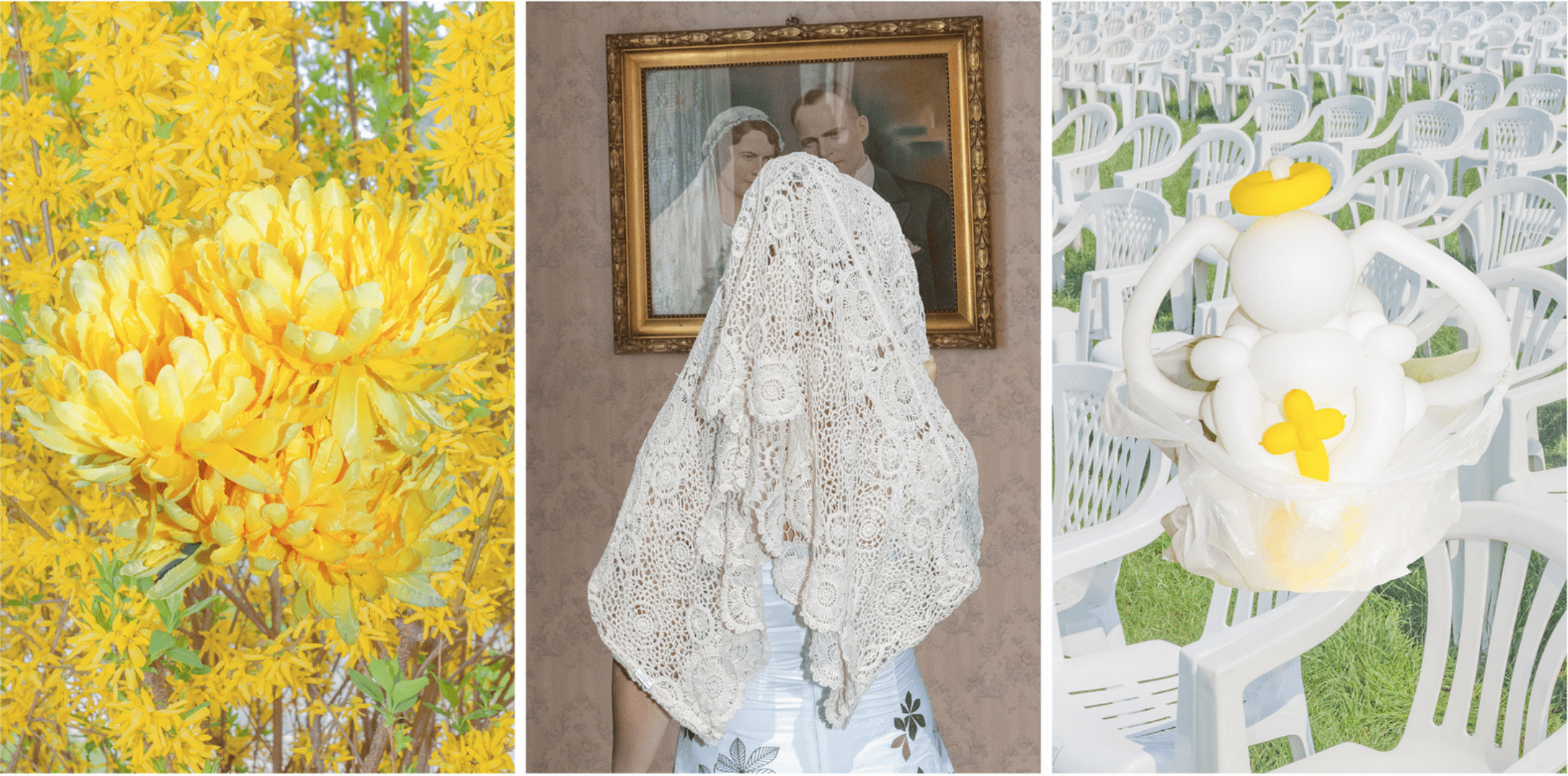

ES: The series Grandmothers On the Edge Of the Heaven is dedicated to my own grandmother. It started when she passed away and creating emotionally explicit collages became a part of my grieving process. Together with Viacheslav, we named this project Heaven because of its spiritual strength and connection to the afterlife, while City of Gardens remained Earth, as it tells the story of a mining past of a Polish city, Katowice.

Most of the grandmothers with their peculiar outfits were photographed by me during the Farewell, a religious celebration that invites Christians to atone for their sins. On this occasion, women put on their best outfits – leopard prints, shiny fabrics, white lace kerchiefs, and bright floral dresses. In order not to lose an important moment, I don’t usually ask for permission to click. Luckily, the majority of grandmothers love being photographed. When they see a camera, they automatically strike a pose.

Tell us about the use of collage in your projects. What do you attempt to convey with this technique?

ES: Every time I created a picture for the Grandmothers’ series, I plunged into the memories and my feeling of sadness was gradually fading away. The art of photography is unique to me because it erases the boundaries of the real and the imaginary. By using photos you are not only displaying the moments that are happening or that have happened sometime in the past, but also, create a new reality. Therefore, in this project, I use the collage technique as I’d like to immerse the grandmothers in the landscapes of an expected paradise. It was important to physically move the grandmothers’ figures – cut out one image and glue it onto another. It felt like transplanting a fish from an aquarium with dirty water into its natural environment, letting it go.

From City of Gardens, it becomes clear that your work is focused not only on Ukraine, but also on other countries and cultures. What motivates you to start a photographic project?

Viacheslav Poliakov: We mostly work with Ukrainian themes as our country encompasses all the stories that concern us and that are waiting to be told. However, we do not limit ourselves to the state.

In order not to lose an important moment, I don’t usually ask for permission to click.”

Is there a theme that is constantly repeated in your work?

VP: In our series, we focus on small cities and provinces, death, both human and cultural and the theme of creativity and the author. There is always a persistent question in our work: where is the place for creativity when for every problem there is a solution that can be copied and not invented?

Your work is very bright, is there a specific concept behind your choice of colours and their combinations?

VP: The colours are largely documentary: they either convey reality or its perception. And actually, Ukraine is very colourful. It’s full of chaotic shades and tints, and all we can do is to embrace all this and work with it.

ES: Only in Grandmothers’ I consciously worked with colour trying as much as possible to bring the image closer to the religious Icon Painting Tradition, where each colour is symbolic. I used a lot of blue, which has the religious interpretation of the infinity of the sky and eternal peace. In the Icon Paintings, one can encounter a lot of red backgrounds as a symbol of victory of life over death and a triumph of eternal life. I also opted for this colour in my work because of its strong symbolism.

What will happen to the city and the country that is now empty because no one wants to live there?”

Your projects are well received in the Netherlands. But how do Ukrainian people see and interpret your work?

VP: Each person interprets our work differently. Some recognise in the images the world around and others are puzzled with the ambiguity of the composition. In the West, our duo is often considered exotic. However, at home, we are perceived as a mockery.

Lately, Ukraine has been going through hard times. Do you think this is the right moment for the birth and prosperity of art in the country?

VP: In my opinion, art becomes more fascinating during conflicts. Media made Ukraine very attractive to photographers as it has been positioned in the news as a country where one can encounter the most unexpected story right in someone’s backyard. And this is true, as strange as it may sound, modern Ukraine is a very free country. People do anything they want, even if it is forbidden by law, which is bad and good at the same time. Also, thanks to the internet and low-cost flights that started to pop up with the recent popularity of the country, Ukrainian photographers got hold of better references and inspirations. However, I cannot omit that artists too surrender more often during times of crisis, as they need to feed themselves and not just with art.

In the West, our duo is often considered exotic. However, at home, we are perceived as a mockery.”

Does your art convey any socio-political motives?

VP: This same question constantly resonates in my head when I am travelling in Ukraine. All these people and cities, such as our native Kherson and Chervonograd, are currently in a state of decay and degradation. So, should they just disappear? What will happen to the city and the country that is now empty because no one wants to live there? And what will remain? Only grandmothers waiting for their death and the mafia that guards a piece of land in order to build a new luxury housing complex?

Are you currently working on something new? If so, what is your new project about?

ES: We are now in the process of organising our personal exhibition Heroic Epic in the gallery Szara in Katowice, Poland in mid-June. This showcase is very important as we will present the images of Poland to the Poles and create a Polish-Ukrainian universal art space. Our idea is to explain the embedded in society legends that manage to turn problems into adventures, and drama into a promoting tool. Interesting enough, vivid (or heroic) stories quickly supplant the mundane in human memory and consciousness. They take root, gain material weight and even create a fourth dimension. The goal of the exhibition is to communicate the heroic epic of the former industrial and now touristy city Katowice through colourful yet ambiguous photo-collages.

Besides the exhibition, I have been working on a new personal project in Warsaw. I am participating in the semi-annual Ministry of Culture of Poland artist residency. Together with photographer and my tutor Rafał Milach, we are exploring the topic of fascism in modern Europe.

Where is the place for creativity when for every problem there is a solution that can be copied and not invented?”

Where do you look for inspiration?

VP: I don’t think we have to look hard for inspiration. In Ukraine, a creative impulse can be achieved by going out for a walk or even by skimming through your Facebook feed. In fact, we are rather looking for solutions, which is more difficult, believe me.