Over the course of ten years, Giulio Di Sturco (b.1979, Italy) travelled more than 4,000 km following the Ganges from its source in the Himalayas in India to its delta in the Bay of Bengal in Bangladesh. The trip resulted in the book Ganga Ma (published by GOST Books), consisting of a series of pastel-tinted landscapes and touching portraits. The photographs tell a story of spirituality defeated by pollution, industrialisation and climate change. GUP talked to Di Sturco and asked him some questions about the project.

First of all, congratulations on your first monograph! How does it feel to have a printed book available to the public?

It’s very rewarding – and somewhat terrifying – to see a 10-year project finally talking book form. My publisher GOST and I put a lot of time and effort in this monograph and I am really happy about the result. We launched the book at Photo London, and I am now looking forward to next month’s presentation at Polycopies in Paris.

What made you decide to move to India and live there for a long period of time?

After I finished university in Rome, I moved to Canada for a few years. While in Toronto, a friend of mine asked me if I wanted to move to India and I thought “Why not!”. Back then, I didn’t know anything about India, and I was supposed to stay only for six months… but I ended up staying for much longer! India is a very fascinating country, but very contradictory at the same time. It’s so rich of stories to tell. My career as a photojournalist started there, and I spent quite some time covering Kashmir and other social and environmental issues.

The scene of the series is set in India along the river Ganges. Where did your fascination for the Mother Ganges come from and what was the intention of the project?

After some time in India, I felt caged in my photojournalist career: I needed to work on projects that were long-term documentaries rather than short stories. I started travelling to the Ganges for some editorial assignments but soon realised that I could dedicate more time to the river, focussing on issues such as climate change, industrialisation, and pollution.

The photos I took in the first period reflected the idea that Western people have about India. I must admit that it took me some time to get rid of all those preconceptions and experience India – and photography itself – in a different way. I had to move away from photojournalism and slow down, take time to see things in a new light. At the time I had no idea that this project would take ten years, nor that it would become a book.

During your 4,000km trip along the Ganges, did you get in touch with any locals, and if so, could you tell us something about their relation to the Ganges?

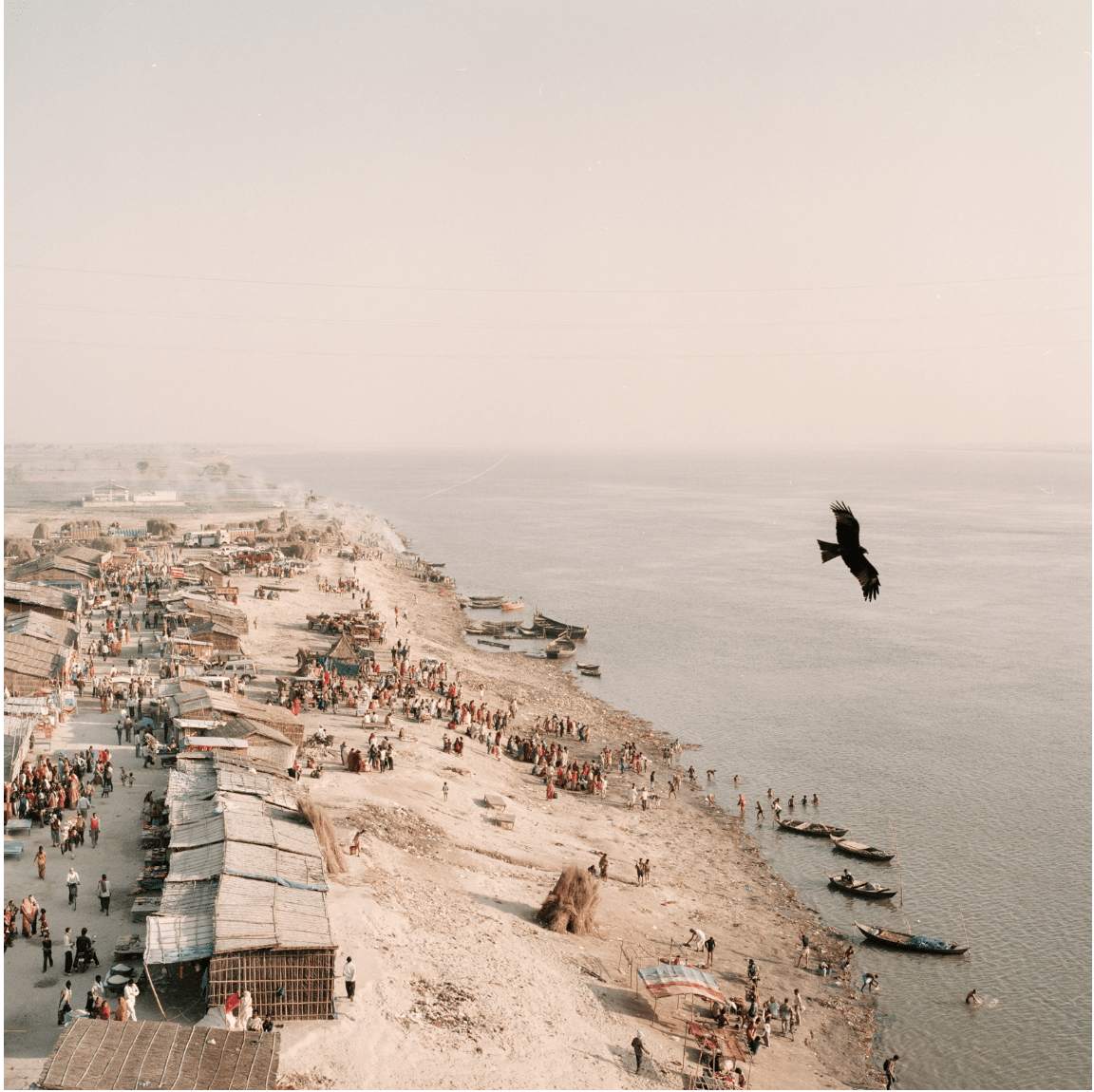

I believe that the Ganges is a powerful metaphor of mankind’s conflicted approach to the environment, being intimately connected with every aspect – physical and spiritual – of Indian life. The sacred river has seen its water levels shrink and turn toxic, endangering the livelihoods of over 400 million people who depend on it for their sustenance, decimating countless species, and spoiling essential natural resources. It is clear that the river is on the brink of a humanitarian crisis and an ecological disaster, but many still think that the Ganges is able to clean itself. Of course, people know that the river is somehow polluted, but most of them have no idea of how bad the situation is. For example, once I did a story about the tanneries in Kanpur, one of the most polluted areas along the river. In Kanpur you can actually see the black water full of chemicals running from the factories straight into the river. The water was incredibly polluted – way more than I had realised up until that point. When I asked my Indian fixer if he was still going to bathe in the Ganges despite what we had seen in Kanpur, he said: “It’s part of my religion, so even though I know it’s polluted, I can’t avoid washing my sins in the river’.

How did you decide on, and how did you realise, the specific aesthetic for this project?

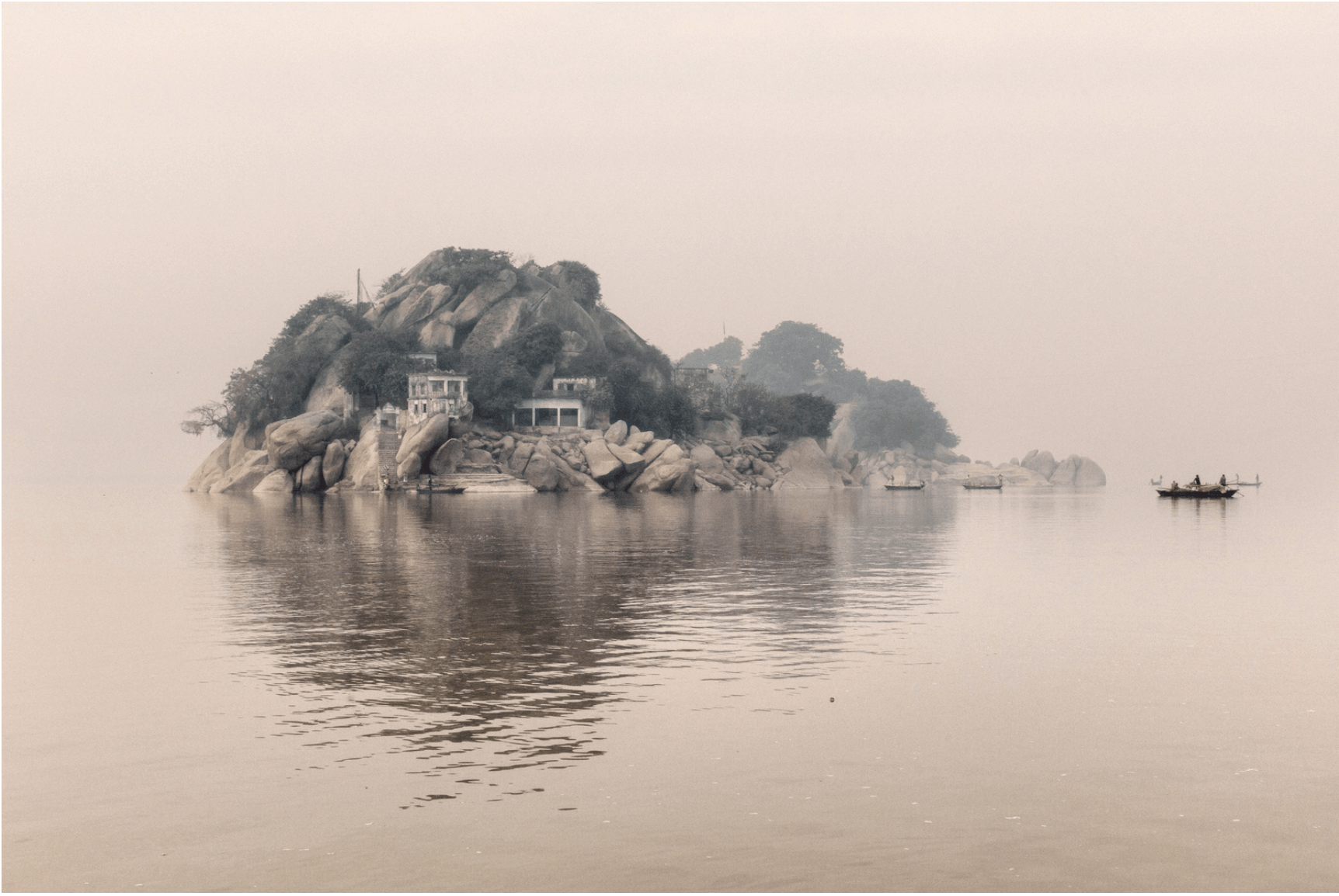

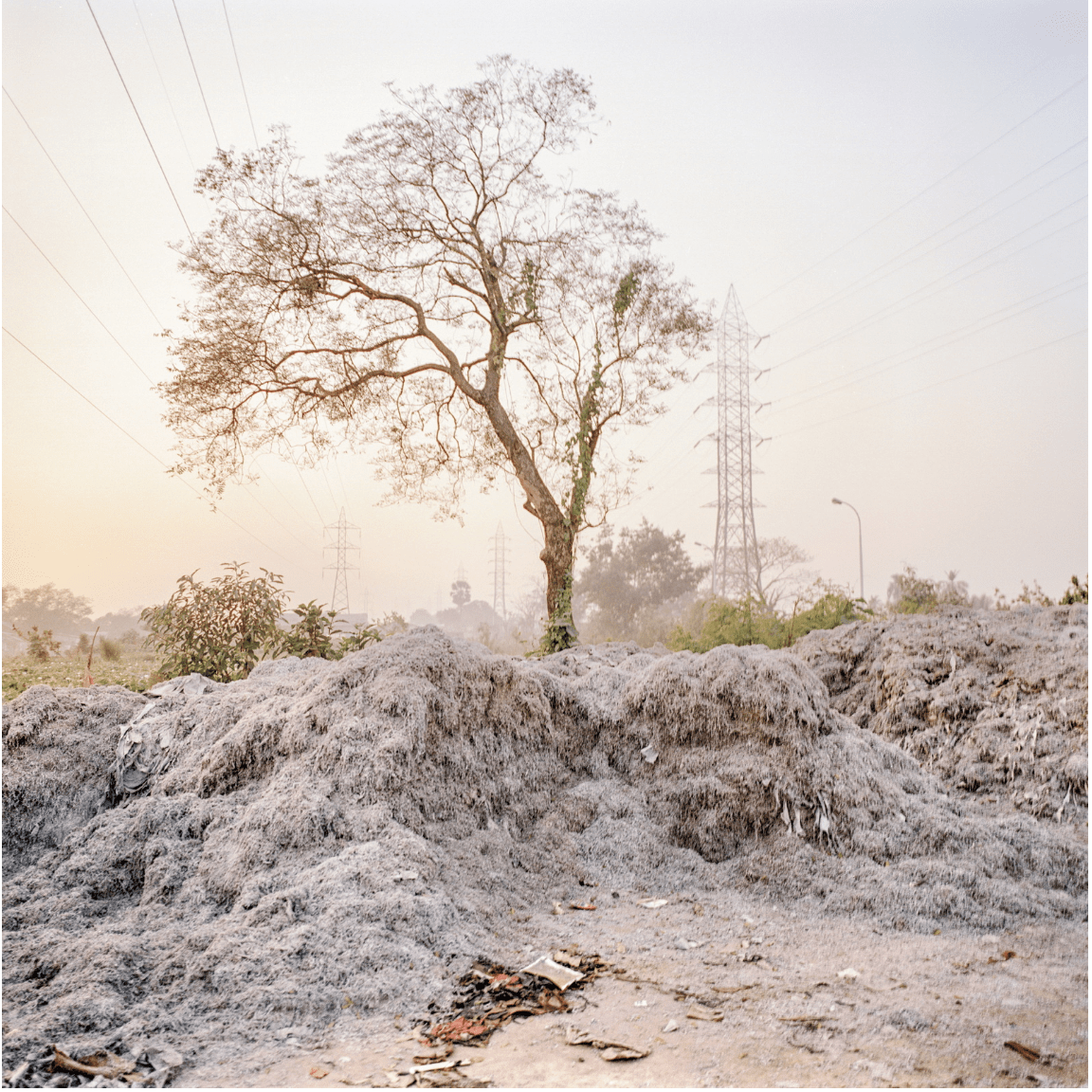

In India, especially during winter mornings, there’s haze in the air. It’s a mix of humidity and pollution, through which the light shines creating a this very peculiar chromatic effect. I chose to shoot only between 6am and 9am, in order to capture the same colours and atmosphere, and to have the same quality and mood in all the pictures.

The idea behind this is to create a new aesthetic of pollution. I think we are a bit saturated by images of pollution in the press: hundreds of pictures of plastic bottles and seagulls covered in oil that we keep seeing over and over on TV and in magazines. If you are able to talk about an issue in a different way, I think it will have a much bigger impact on the viewer. At first glance, Ganga Ma’s images appear beautiful and poetic, and people actually stop and look at them. But if you look again, you understand that there is a second level and that the pictures reveal a much darker truth.

Are there any projects currently in the making?

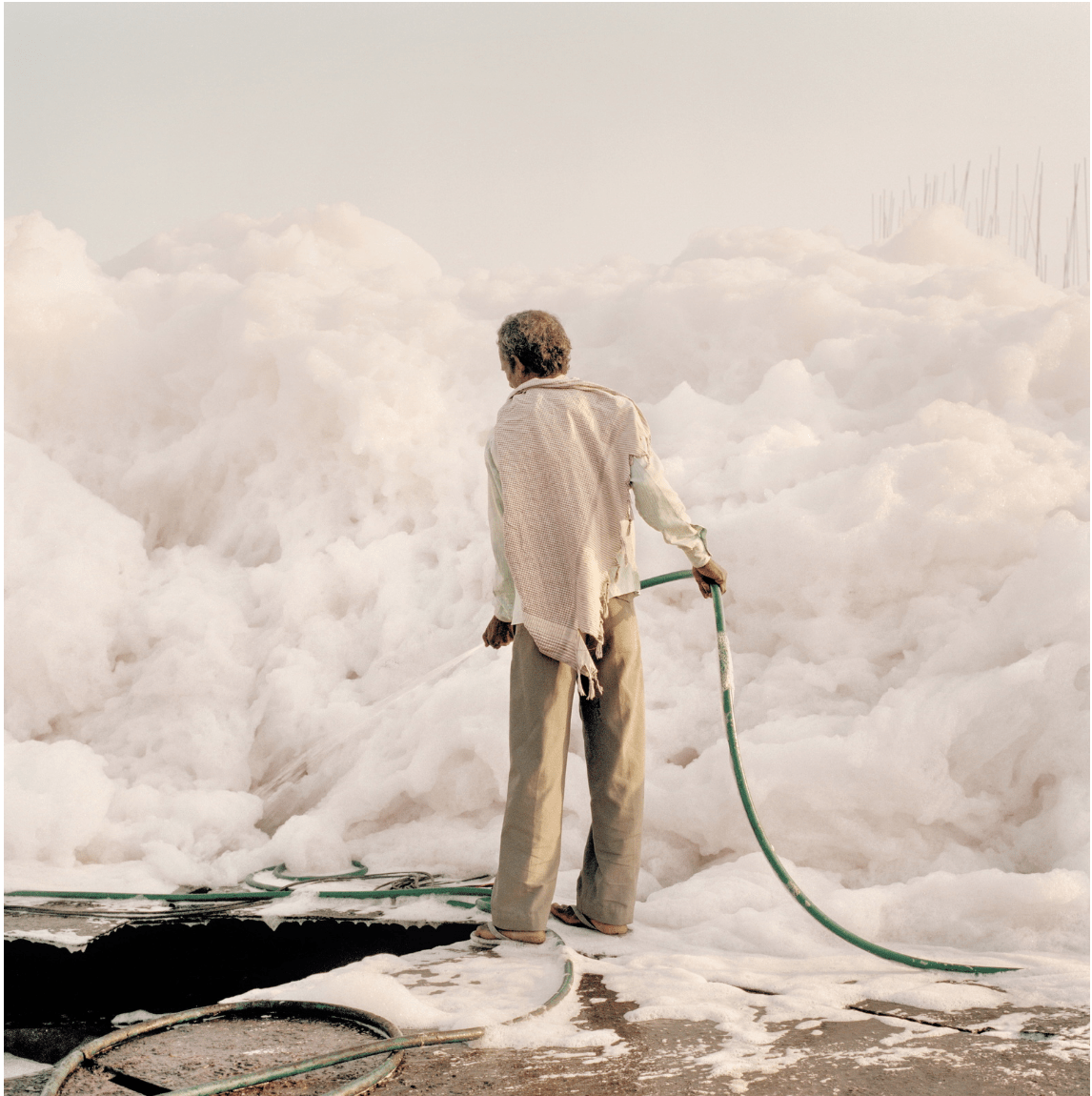

Still a lot is happening around Ganga Ma. A selection of works from this series is currently exhibited at the French festival Photaumnales, whose theme this year is ‘Terra Nostra – The Age of Anthropocene’. I am really happy and humbled that one of the most iconic images of Ganga Ma – the photograph of a man trying to tame a huge iceberg of chemical foam with a tiny water hose, has been chosen as the official poster of the festival.

Beside this, over 20 large-format prints of Ganga Ma are on show at the Podbielski Contemporary gallery in Milan until 15th November.

In terms of new projects, I am shooting the final chapters of another project I have been working on for a few years now: Aerotropolis The Way We Will Live Next, which was the winner of the Getty Grant 2018 and was nominated for this year’s Prix Pictet 2019. More soon!