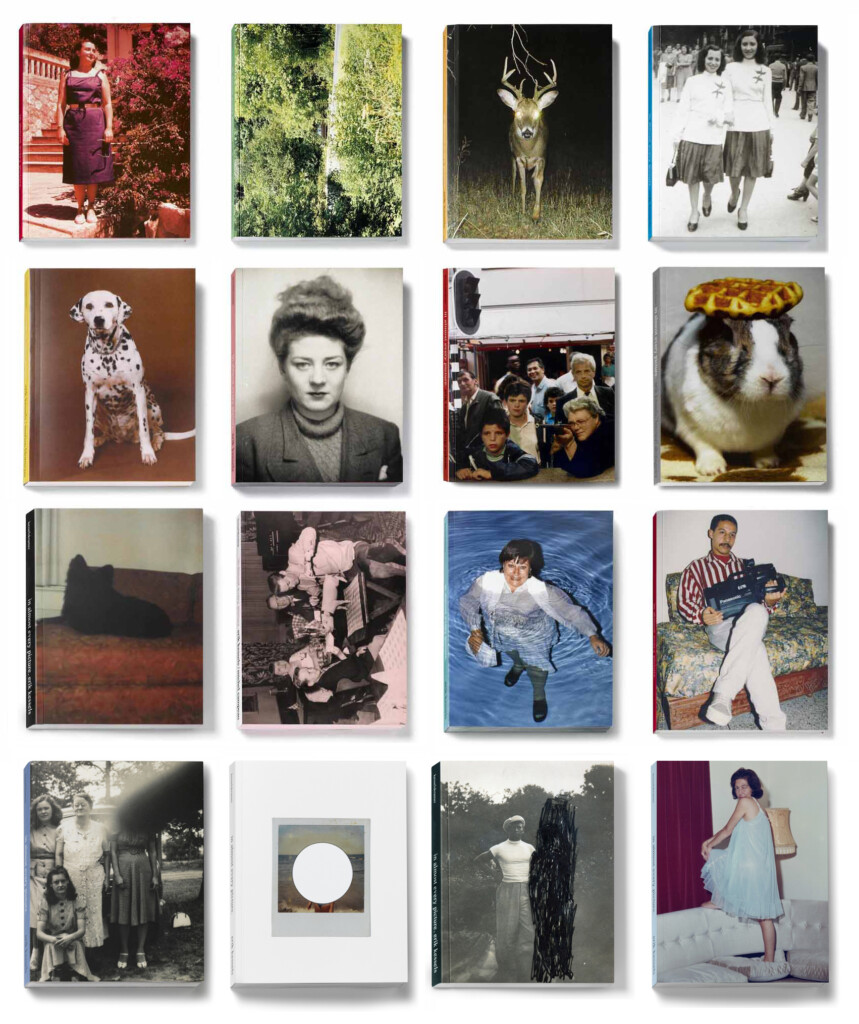

In ‘Almost Every Picture’ is a series of books focusing on found amateur pictures. Each volume in the series arrives from a collection of “vernacular” photographs sourced from flea markets, the internet and from found photo albums. These publications (the first one dating from 2001) touch on both social history and personal biography.

Dutch artist Erik Kessels (Roermond, 1966) is the driving force behind In Almost Every Picture. During the last twenty years, with these volumes, he gave way to an intimate view into the private lives of strangers. He recently published Sexy Sofa – no. 16 of In Almost Every Picture and we thought it a nice opportunity to have a chat with Erik.

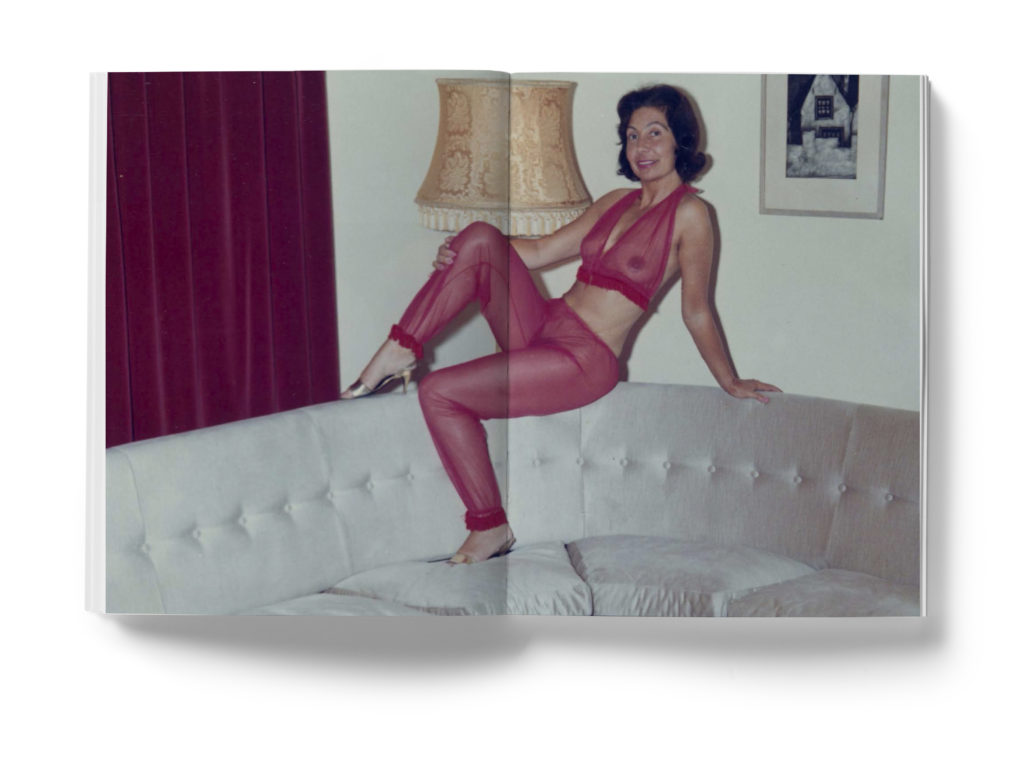

You recently released In Almost Every Picture #16 – Sexy Sofa. What is the story here?

I received the images from the daughters of the couple. They didn’t have access to all this until the death of their parents. These ladies, now in their fifties, got in touch with me on their own initiative and then brought me a box containing films, slides, albums, where 90% of the material was their father photographing their mother in erotic poses. The married couple kept on going with this peculiar erotic-game for almost a decade, starting from around 1965. The other 10% were pictures of the daughters in their youth and holidays and other things.

Was the story immediately clear or how did you eventually edit all the material?

From all this material dated from the early 1970s, it becomes clear that the woman in the pictures is the muse of the photographer (her husband). It is not pornographic but very erotic, in a way, and the photo sessions come across as a kind of foreplay for this couple – to my understanding at least.

I had the material for 8 or 9 months already, but I was only looking at the beauty of the images at first. I could not find the story, there was no narrative. And then, at a certain moment I find out a little text underneath one picture with the empty sofa, and it said: “We have a new sofa, a new fireplace and we have to christen it.” That’s what kicked it.

More in general, how do you explain your long-term interest and involvement with ‘vernacular photography’?

I was 11 years old when my sister died. She was 9 and driven over by a car, in our hometown in the South of The Netherlands. By way of grieving, my parents started to look at images of her in an album and they also cropped one portrait of her out of one of the images, enlarged, and reversed it from colour to b/w. This somehow consoled them. For myself, besides the tragic event itself, having had that picture on the wall in my youth somehow made for an early interest in the appropriation of personal archives.

But the interest also relates to my professional background, my career as an art director working in advertising, design and communication. I worked a lot with photographers, but I never had the ambition to become a practicing photographer myself. I didn’t feel the need to add more pictures to what already existed but meanwhile, my private hobby was (and still is) visiting flea markets, especially in Brussels. That is where I started to become attracted to family albums and vernacular pictures that, aesthetically and in their purpose, were quite far removed from the perfect photos I needed for my job in communication.

This ‘hobby’ eventually led to the first publication of In Almost Every Picture, about 20 years ago. How did that happen?

The amateur image is something I got very much attracted to. But single vintage photographs are not that interesting to me. I am more interested in the story.

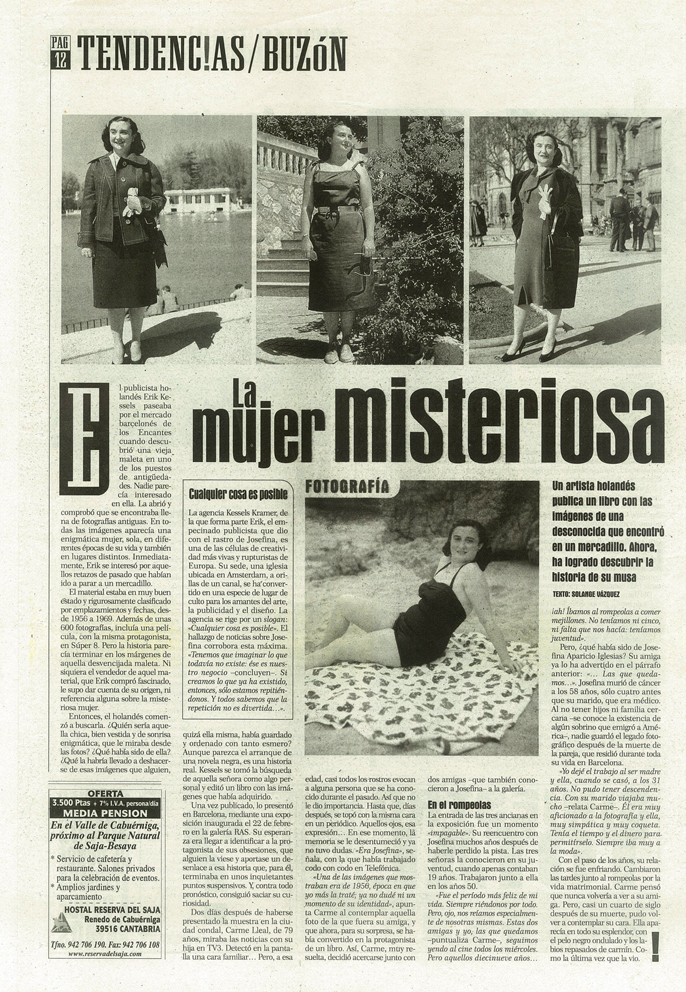

In 1999, I stumbled on 400 images of a Spanish woman. I found these images in Barcelona, on a local flea market. I had them for two years, and only later I found out that that it was a series related to a private project of a couple that went on for over a decade. The woman was serving as a muse for her husband. He must have photographed her for a period of 14 years. I showed it to many people at that time, in a lightbox, and at some point, someone said: “Why don’t you do something with it, make it seen by the public.” So that is basically how it started.

Did you ever get to meet them in real life?

When the book about the couple was finished, I went back to Barcelona again, and I contacted newspapers, saying that I came from Holland, explaining about the book and that I wanted to know if the woman seen in the pictures was still alive. Many newspapers wrote articles about it. El País, in a full-page article, referred to her as “La Señora Ex” or “La mujer misteriosa”. It was even on the Spanish national news, and then a woman came to me because she recognized the woman in the pictures – she was working on a telephone company with her – and this is how I learned that the couple had died years before. That is also why an album like this ends up on a flea market. Where I find them, they are often “in the garbage”. They are on the floor in the market or on somebody’s attic.

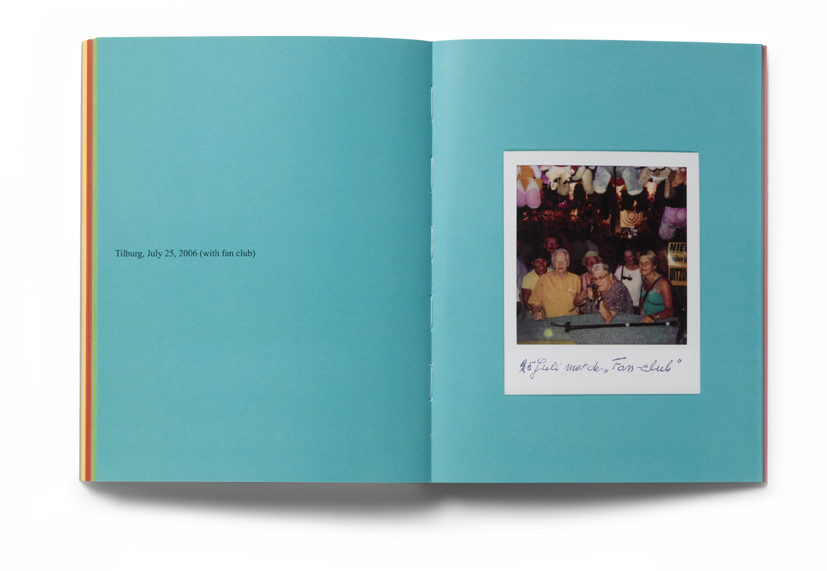

I strongly feel that there should always be a sense of ethics behind the renewed display of vernacular material. Meeting the people is therefore part of the project, when possible, and the relationships involved also extend beyond the moment of publication. This was the case with Ria, for example, the woman who went shooting her self-portrait with a rifle at the yearly fair (In Almost Every Picture #7). The Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam purchased the originals, and she got paid for it. Rita then started to give parties and bus trips for the elderly home and burnt all the money like that. I am very much attached to her. My fascination is that everyone can become your family. Sometimes fictional, sometimes hilarious. It’s quite nice.

“I strongly feel that there should always be a sense of ethics behind the renewed display of vernacular material.”

Can we say that all your stories are true?

That’s a good point. All the pictures are true, and there is no manipulation in them, but maybe there is sometimes a manipulation in the story. The narrative might for some part be based on my interpretation or assumption. This is the case for some of the volumes of ‘In Almost Every Picture’.

I’m also seeing recurring themes in the albums that I’m attracted to – love, sex, death, family. People have secrets for all their lives and only when they die these kinds of remarkable habits, fetishes and compulsive acts come to the surface.

“All the pictures are true, and there is no manipulation in them, but maybe there is sometimes a manipulation in the story.”

In a sense, it is also sociological research.

Yeah, when I edited the images for the first book, I put them in chronological order. That’s how I noticed how the woman was photographed further and further removed from the camera – so seen as getting smaller within each next image. From this, I concluded that – apparently – she and her husband must have psychologically departed a little bit from each other over time, which would then explain the physical distance between them. Maybe her husband started to grow an interest in the background or maybe she didn’t want to be photographed from up close anymore. I’ve noticed something similar, the same dynamics, in other albums too. I would say that you can see how long-term relationships alter over the years that they’ve spent together as a couple. It is this kind of bittersweet aspect reflecting from the found footage that I’m interested in.

“People have secrets for all their lives and only when they die these kinds of remarkable habits, fetishes and compulsive acts come to the surface.”