Diana Tamane (b. 1986, Latvia) is a visual artist working between Tartu, Estonia and Riga, Latvia. In her work, she primarily uses the medium of photography in addition to video, sound, text and archive.

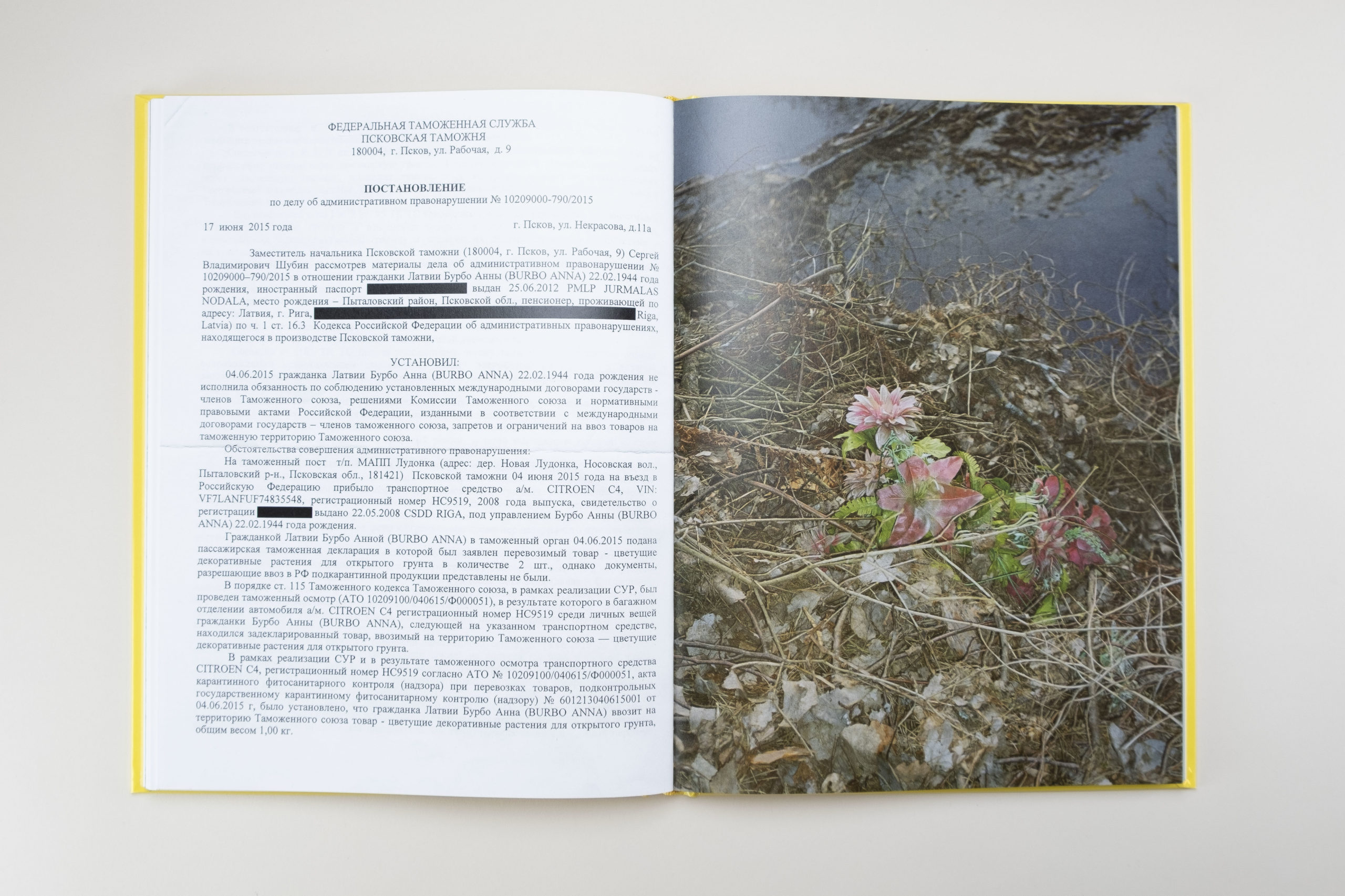

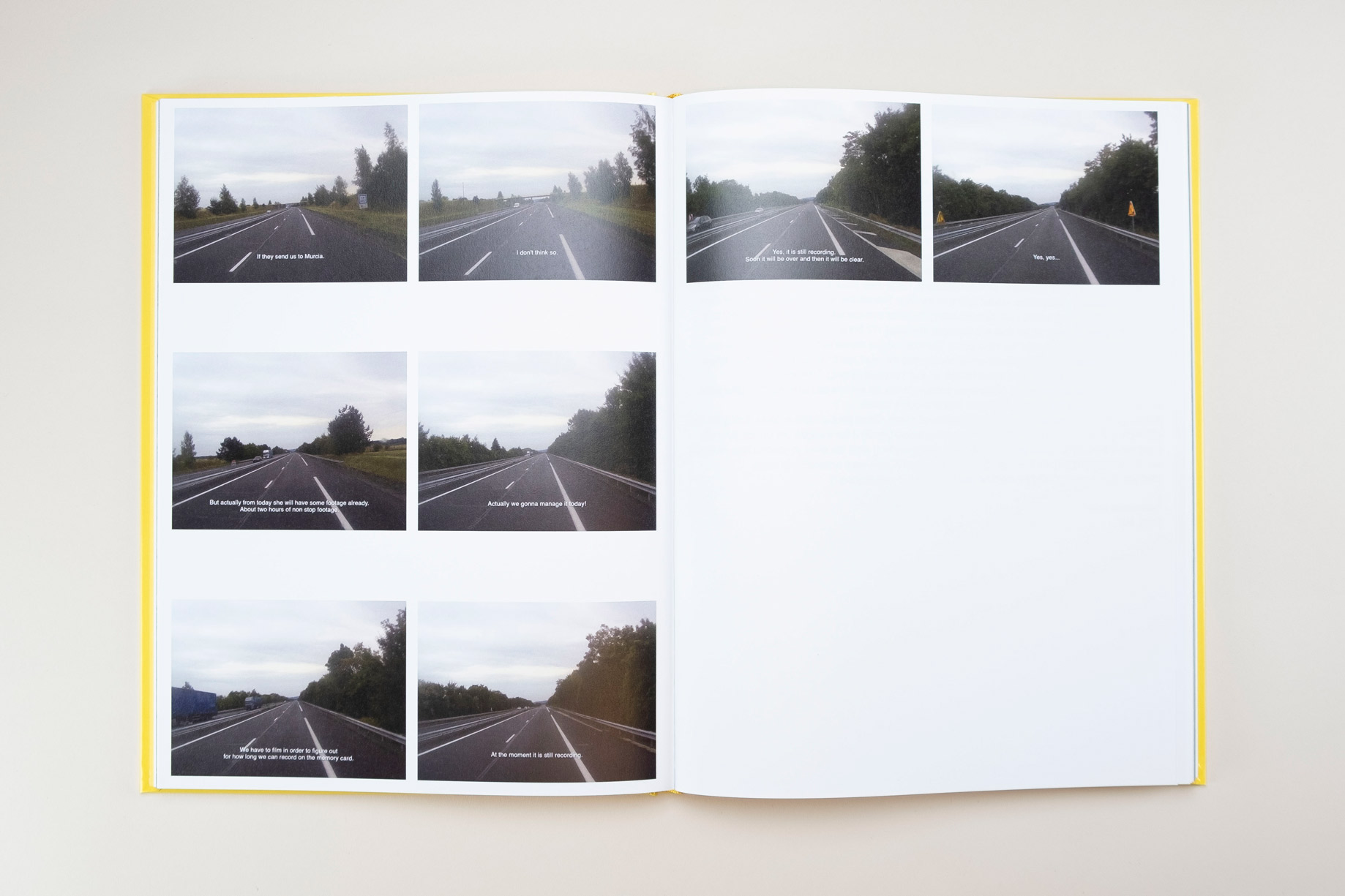

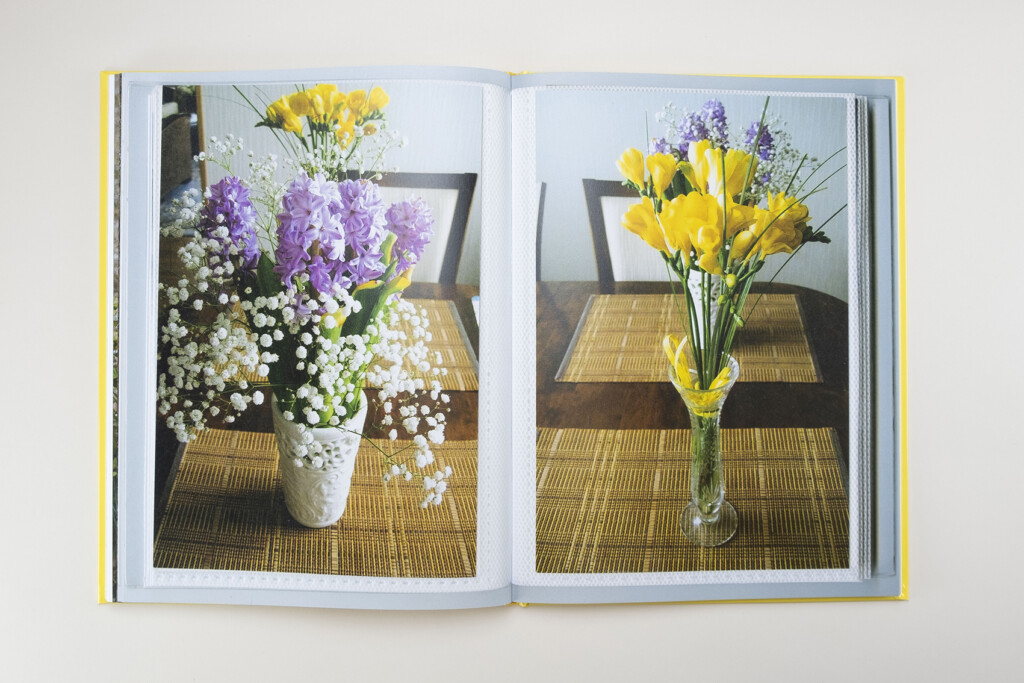

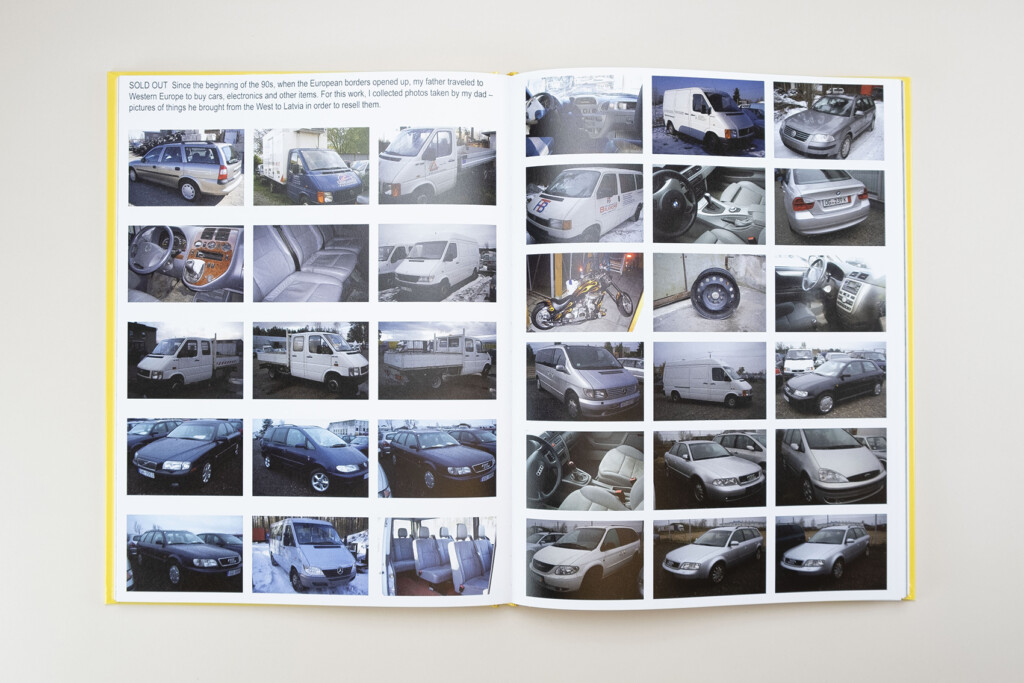

Tamane’s work is centred around daily life where both herself and her family are involved. Her latest publication ‘Flower Smuggler’ (published by Art Paper Editions), consisting of numerous layers that feature visual materials generated by her family over many years. By combining materials like images from the dashcam of her truck-driving mother with her grandmother’s archive or her father’s product palette from the last ten years, she manages to present novel perspectives on Eastern Europe.

In an interview with GUP, Tamane reflects on her way of working as a visual artist – specifically in the context of ‘Flower Smuggler’, winner of the Arles Author Book Award 2020.

‘Flower Smuggler’ can be said to comprise of numerous projects of yours that are connected to your family. What were the decisions you took while editing this book?

The book contains 11 projects made from 2012 to 2019 but I already started working on family matters around 2009/2010. I didn’t include the first project ‘From my Family Album I’ (2010-2012) which was part of my bachelor project at the Tartu Art School, for which both the visuals and my approach differ significantly from how the project eventually evolved.

As my publisher APE treats books as an exhibition space, it was a very interesting process to think about what’s the best way of translating my exhibitions into a book format. As I see my work as one big project, it’s cool to see it finally come together in a book format.

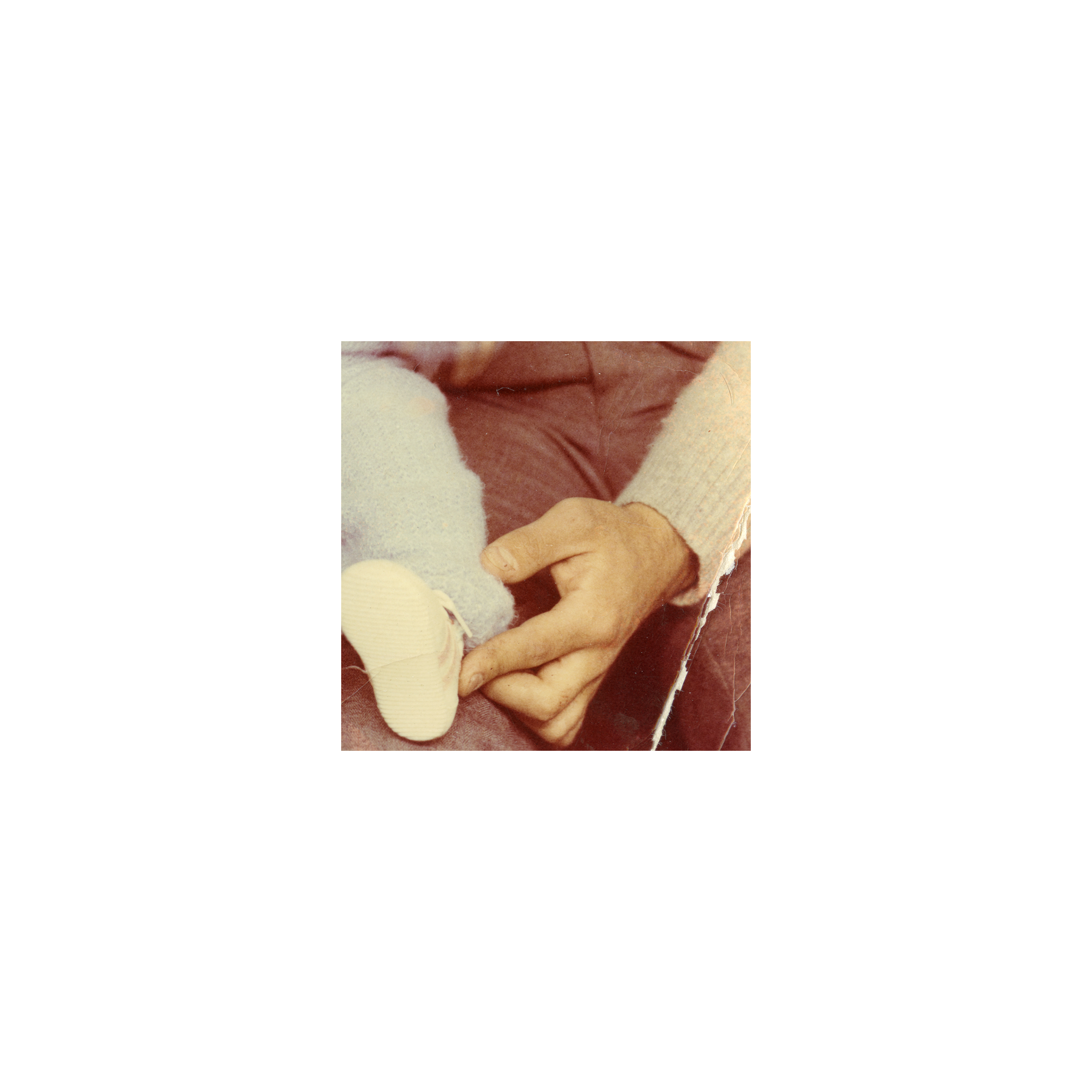

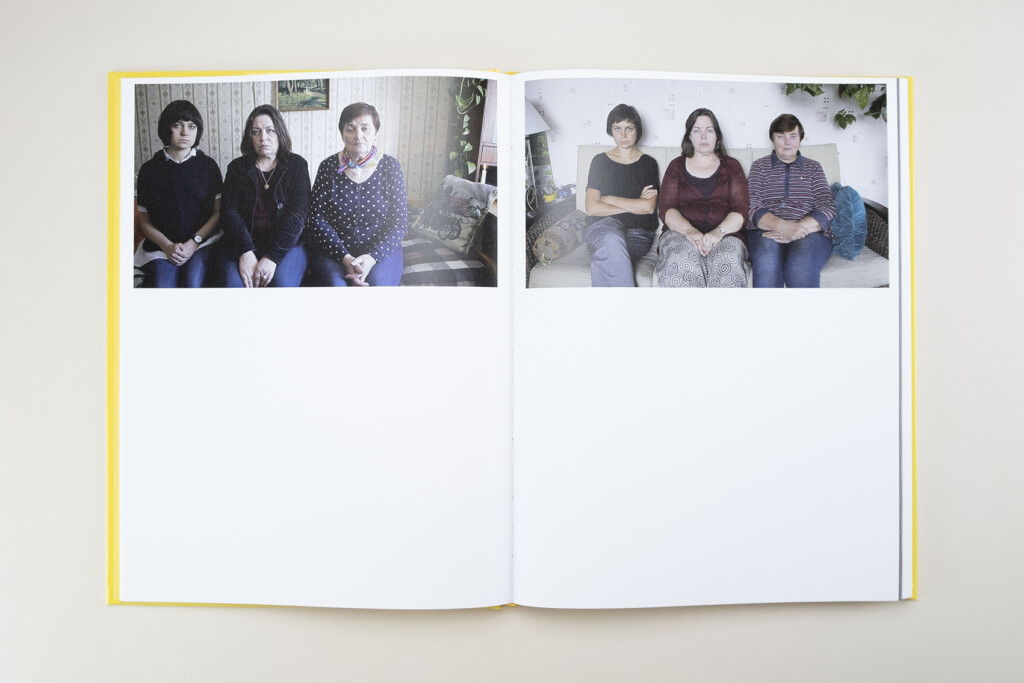

The book starts with my early projects (2012-2015). At that time, I was mostly interested in the psychological aspect of relationships. The projects were more personal, attempting to understand where you come from and where you belong. They were also related to memory, and hence, they were more about the past. Later, I felt an urge to focus more on the present and needed to broaden or open up the subject matter – including its social and historical aspects.

This is how the work transformed from dealing with small distances between people and their gestures towards longer distances and crossing borders. ‘Flower Smuggler’ is very much about my family history, be it related to my truck driving mother or concerning my father who, since the collapse of the Soviet Union, travels back and forth to Germany as a salesman.

In your work, you draw inspiration from your personal life to address more general social issues such as European transformations in the past thirty years. How can the personal become universal in the end?

It’s an interesting question I’ve been asking myself as well. Family can serve as a micro model of society: if we cannot function within it properly, how can we talk about larger transformations? Change starts within us, with the ones close to us, and then with society at large.

I think the personal becomes universal when we are willing to be generous and vulnerable because we all have the same doubts, fears and insecurities regardless of our background. So, whether we are living in different climates, political regimes or centuries, struggles are repeating maybe in different forms, but the essence doesn’t change. Because our ego always wants to be important in the present.

At the same time, it’s good not to take ourselves too seriously. For me, art is like talking to a good friend – sometimes you joke, sometimes you cry, sometimes you talk about politics, sometimes you are just silent in each other’s presence. Art is just a way for me to feel fully alive.

Since your relatives often become co-authors in your projects, were they keen to collaborate from the start?

They were not always keen, no. Also, some were more open than others. However, over time, they became more supportive and eventually, most are willing to collaborate. Sometimes they even give advice on what I should exhibit. It took some time to get to this point, though.

In your book, there is an underlying sense of repetition where for instance, you present an abundance of flower images created by your grandmother or family group portraits taken at the same place, yet at different times. What role does repetition and oscillation between past and present play in your work?

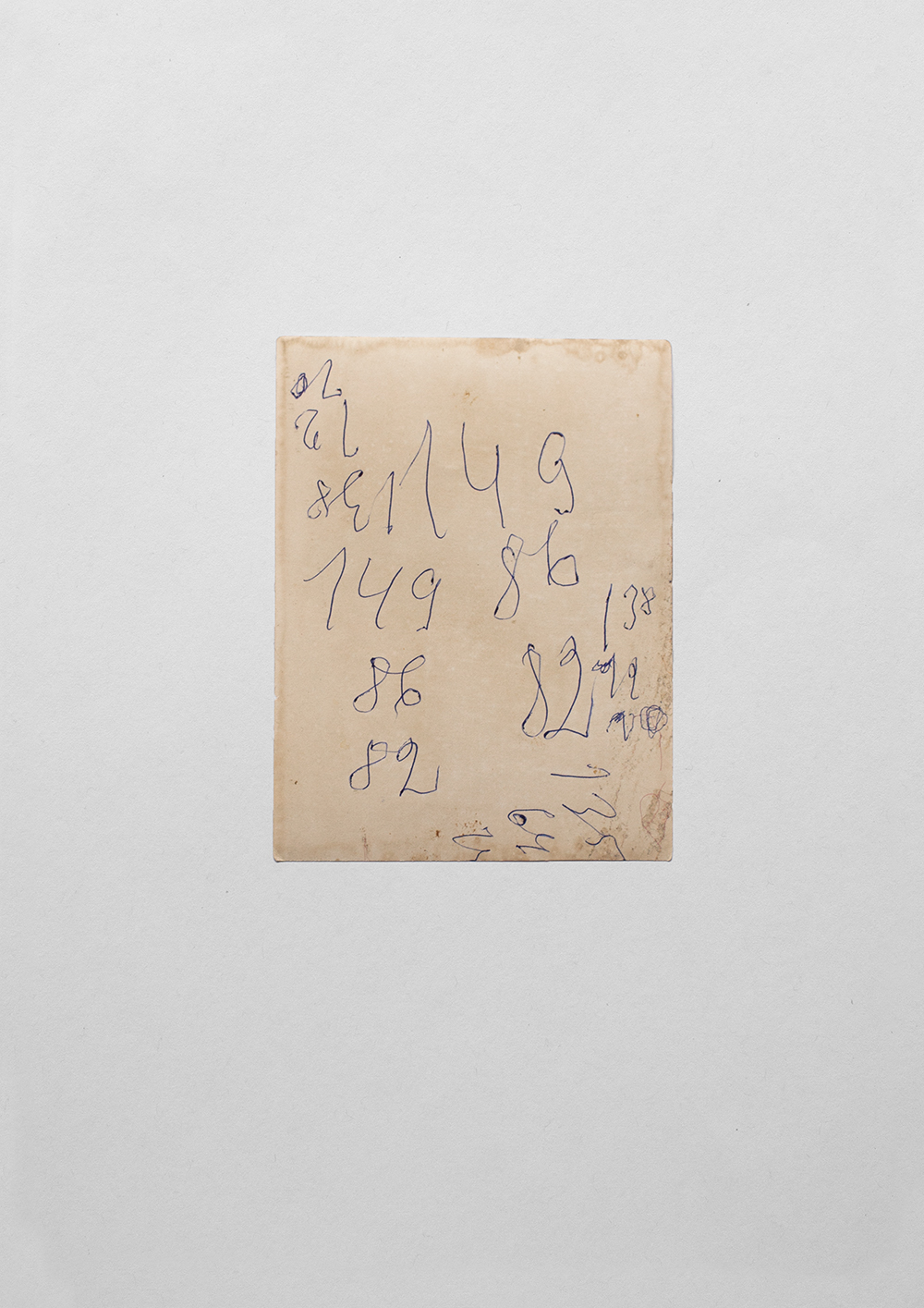

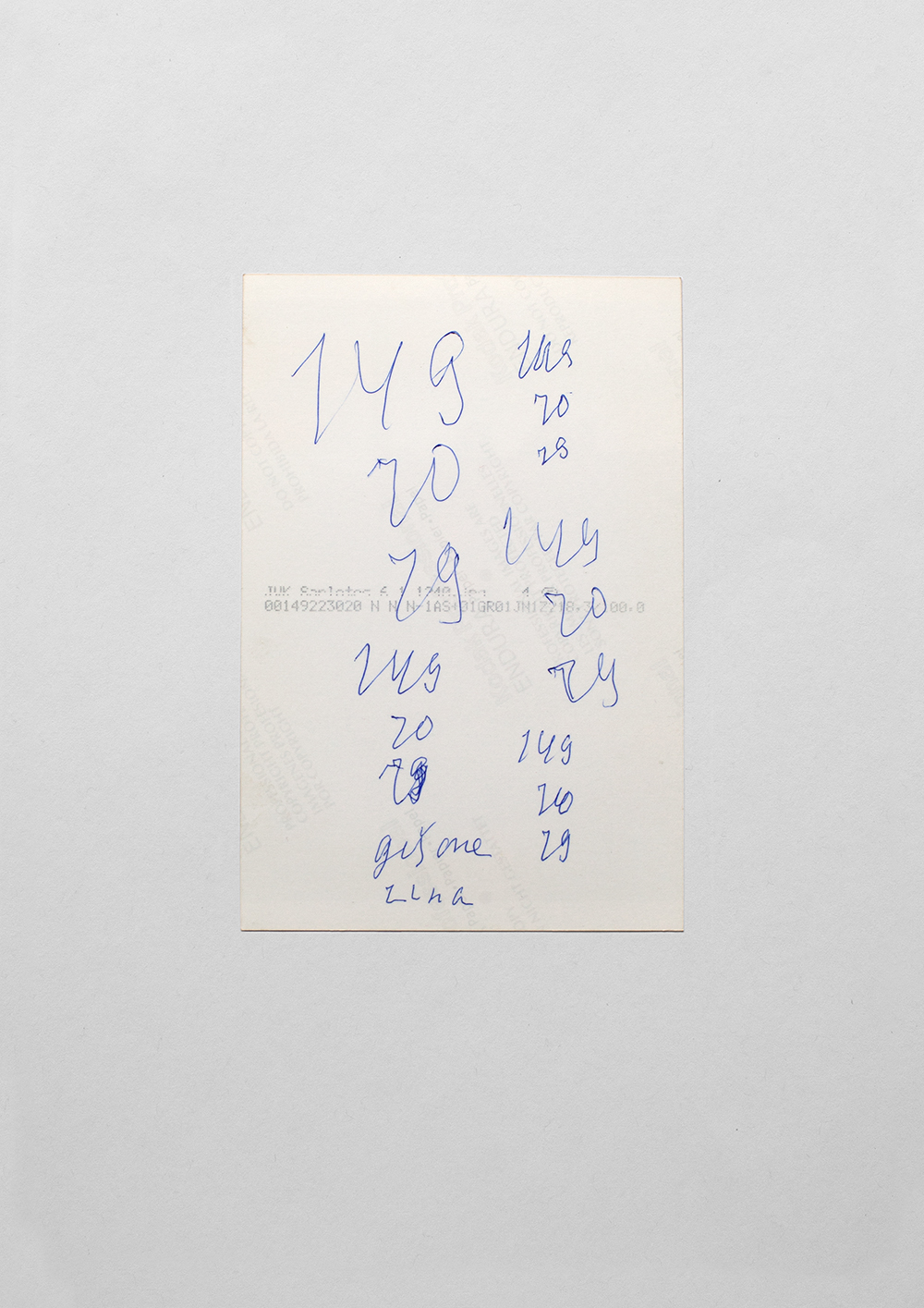

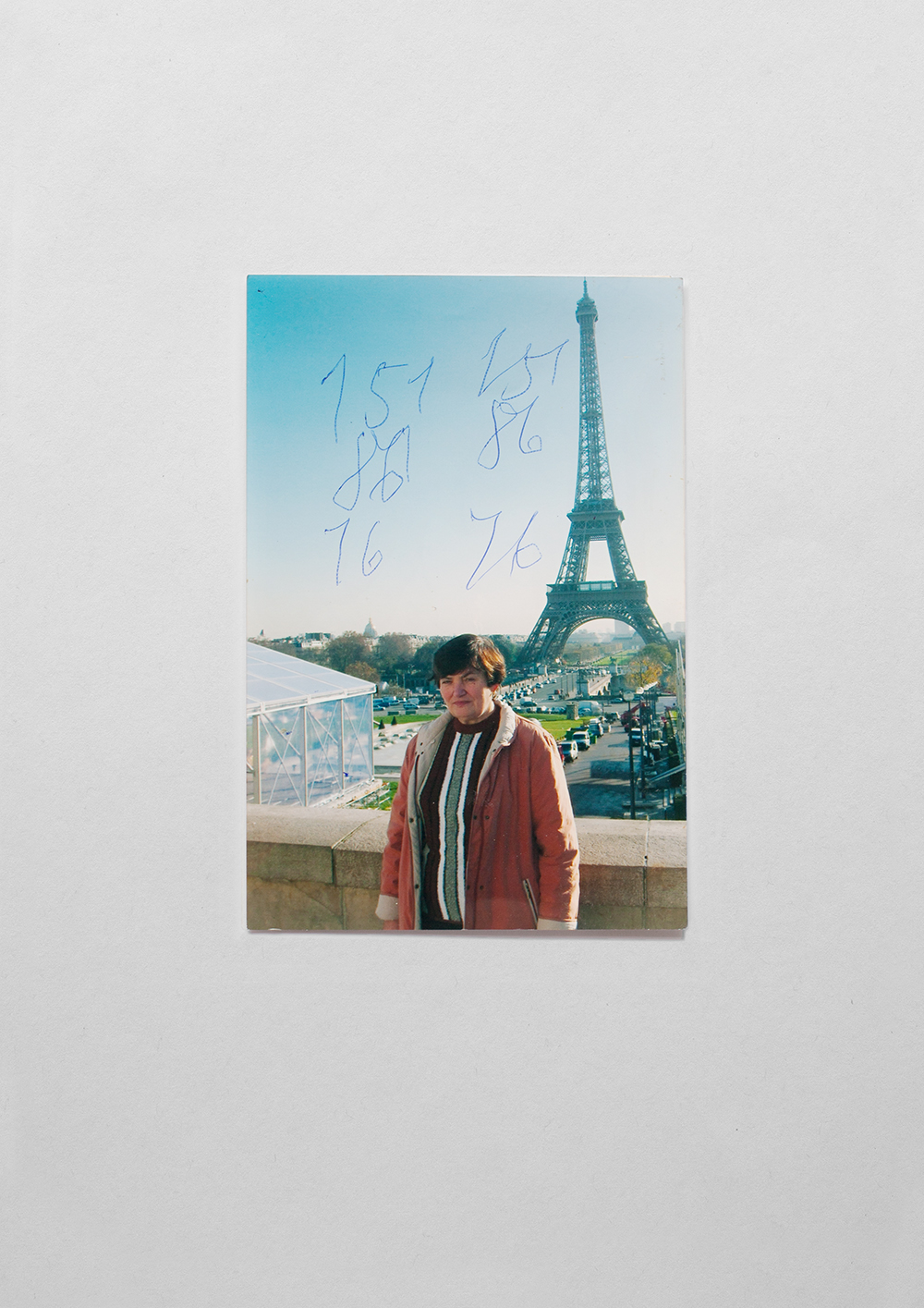

Things gain meaning by repetition and through my approach, the photographs become the portrait of the person. Like in ‘Sold Out’, photographs taken by my father of items he brings from Germany in order to sell, or my grandmother who takes photos of flowers but also is a great gardener, and a “flower smuggler”. Or in ‘Blood pressure’, where my great-grandmother writes down her heartbeat and the blood pressure on the backs of photographs from her family album, which was an important ritual for her. She did it daily even though her blood pressure was not that bad for a 92-year-old.

“Things gain meaning by repetition (…)”

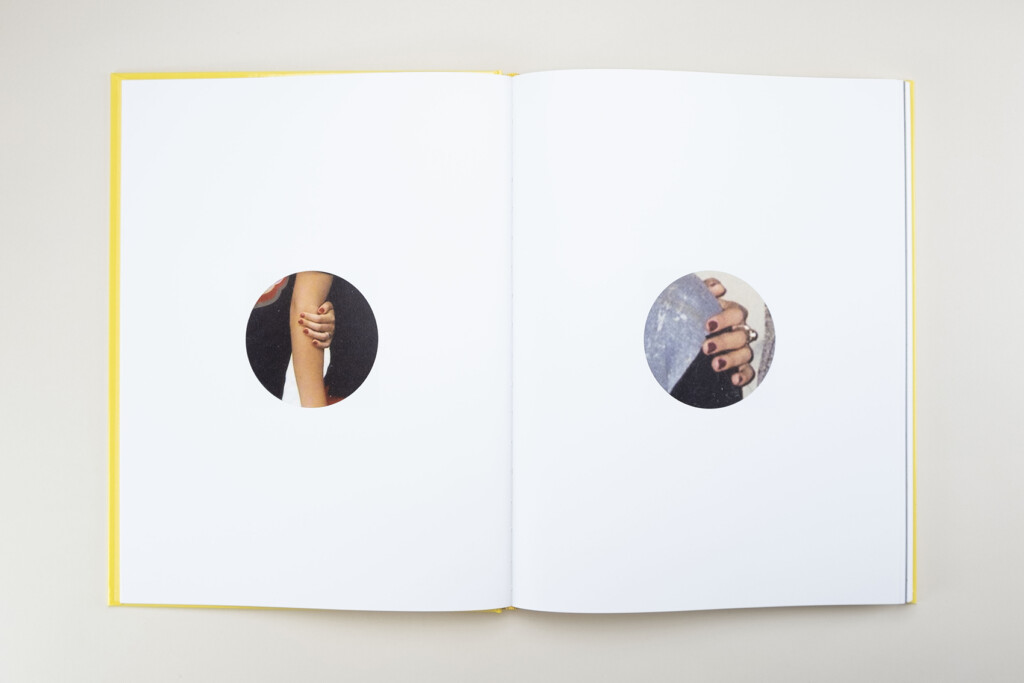

Overall, the images have a strong haptic quality as they emphasize the notion of touch. Would you say that the tangible aspects of photography are a defining factor in your work?

I would say that, in a more general sense, my approach is similar to the feeling of being in a dark room or when trying to photograph something, but the lens doesn’t focus properly. So, it is mainly about physically adjusting to a situation that requires a correction in order to see better – trying to figure out the perfect distance between you and your subject.

The project also includes vernacular objects to overcome my own perspective. At some point, I simply asked myself: “Okay, I am taking this kind of photography, I portray my family in this or that particular way, but how do they actually see it all? What excites them, how do they use this medium, and for what purposes?”

Your life story comes across as anything but ordinary. Or how do you see that?

I am often told that I´ve got quite an extraordinary family, indeed. But I think every family story is extremely interesting! If we look at the things around us for a longer time, they become interesting.

Ordinariness is a big part of our lives, so it’s good to befriend it. I think that, as an artist, it’s important to observe things without some preconceived concepts, judgments and opinions. To keep oneself as open and affectionate as possible and to look at things more with our heart and not so much our brain, regardless of what is in front of us.

Currently, you are exhibiting ‘Letters from Mom III, Mishanya’ alongside drawings created by your mother in ISSP Gallery in Riga. How do you approach your work in an installation form?

There is some kind of fluidity in the way how I exhibit, as all projects are related to each other – the next responds or comments on the previous. In fact, it is one long term project, so I often combine different works depending on the space and ideas I want to emphasize. It can be arranged, for example, around communication with my mum, or around generations of women in my family and their experiences or ideas considering mobility, memory and time.

I often ask myself how I want the viewer to feel and move in the space, whether to be closer or more distant to the work. At the end of the day, I just want the person visiting the show to feel embraced, understood, and comforted.

‘Flower Smuggler’ includes a text by a Belgian curator Martin Germann. The publication has recently been nominated for Paris-Photo Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards and Les Rencontres d’Arles Book Awards 2020. Tamane’s exhibition ‘Within Arm’s Reach’ is currently on view in ISSP Gallery in Riga until the 9th of January 2021. The publication is available for purchase here.