Ciro Battiloro (b. 1984) is an Italian photographer based in Naples. In his work he analyses the human being and its relationships, lived in contexts of discomfort and social neglect. Recently, his research focused on Southern Italy neighbourhoods (Rione Sanità in Napels, Quartiere Santa Lucia in Cosenza) which, after historical processes and building policies, suffer from a gradual ‘ghettoization’.

What’s the connection between these places, semantically, socially or aesthetically?

The neighbourhoods of Rione Sanità (Napels) and Saint Lucia (Cosenza) are known for problems that afflict them: unemployment, school dropouts, social disease. Both have become outskirts of cities, even if they’re located in the historical centres. At the same time these districts are full of humanity and dignified stories.

It’s obvious that the situations are significantly different, due to their histories and cultures. The former is densely populated and it’s living a period of rebirth and revaluation; on the contrary, the latter is experiencing a desolated situation, and the feeling is that an era is coming to an end in Saint Lucia.

What triggered you to go there?

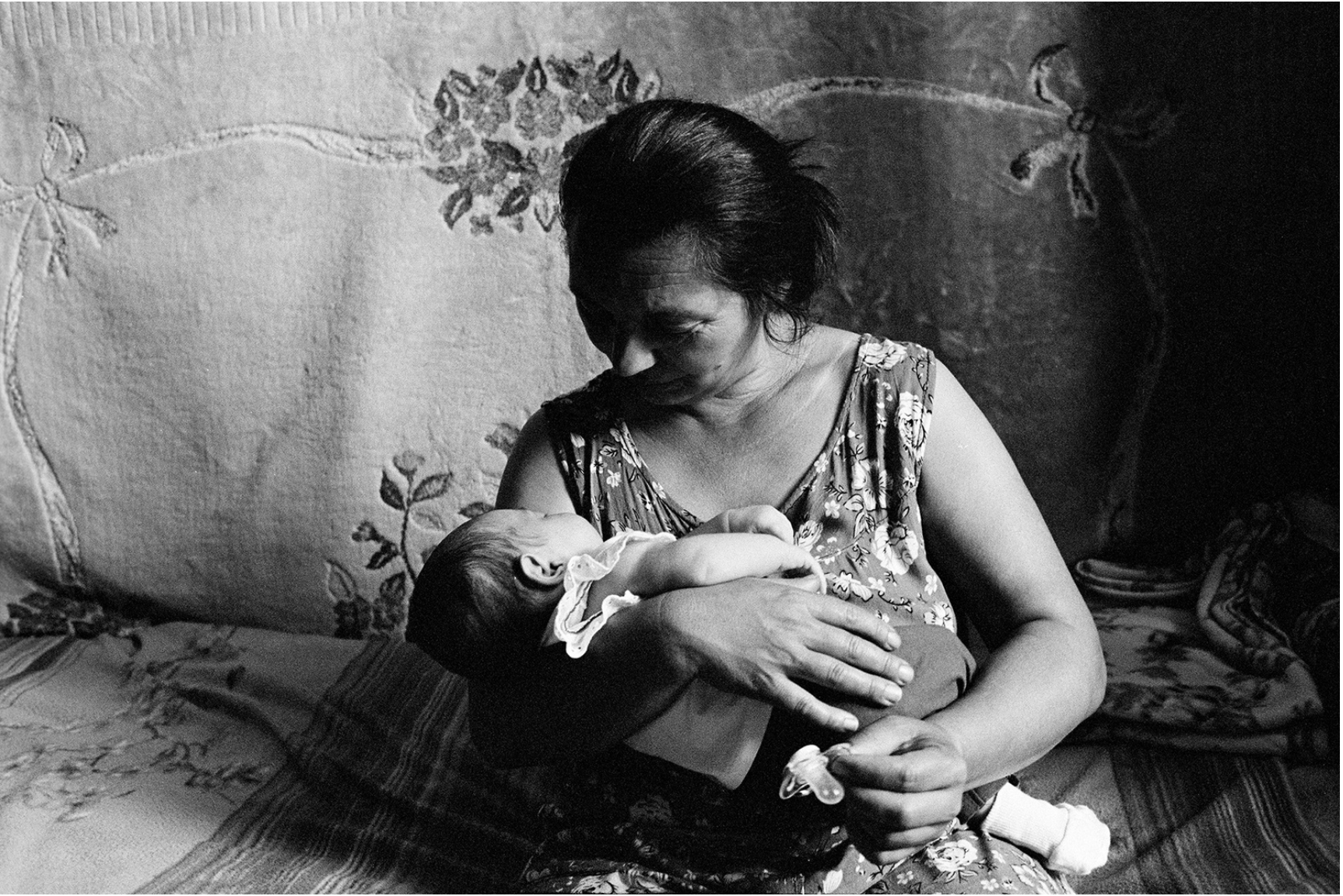

With my research I’m attempting to recover the meaning of life through relationships, neighbourhoods and the families that inhabit them. I am currently focused on southern Italy’s territory, which is ideally and physically close to me. My aim is to address these places without falling into a rhetoric or stereotyped story.

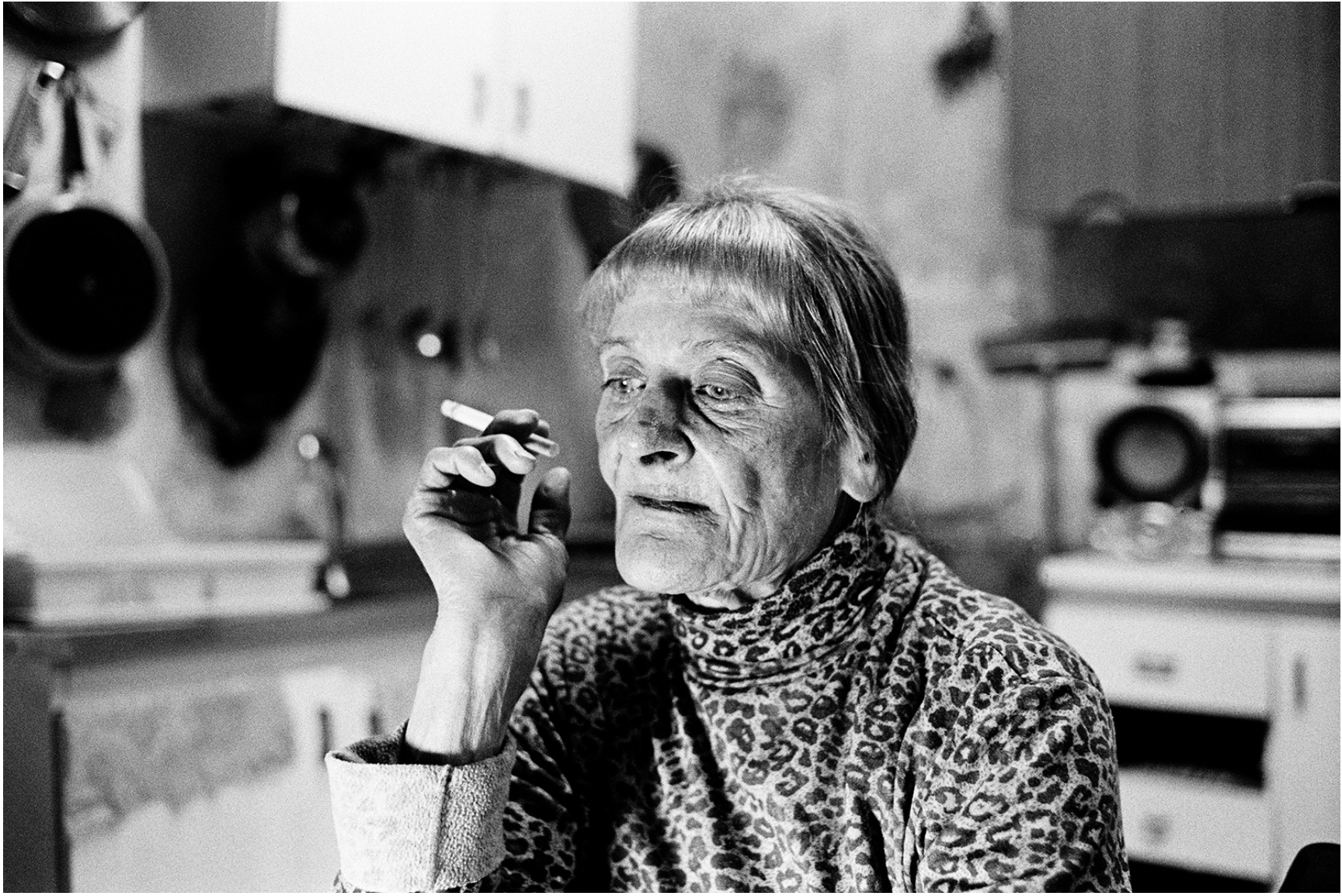

In 2017 I was invited to an artistic residence in Cosenza. In that occasion I started to be interested in the historical centre’s social situation. The district of Santa Lucia was once at the core of the vibrant city life. Also known as the “lucciole” (prostitutes) district, it is a different entity; a parallel world where the decay of its structures finds an echo in the everyday life of its people. Today, the few families and indigenous inhabitants that still live in the Santa Lucia district, have chosen tenaciously not to abandon that place. For them, this is the guardian of their identity and their experiences, despite the constant risk of ruined structures and buildings collapsing.

In both stories, Sanità and Santa Lucia, the camera is strictly on the subjects rather than on the houses or the neighbourhoods at large. Why so?

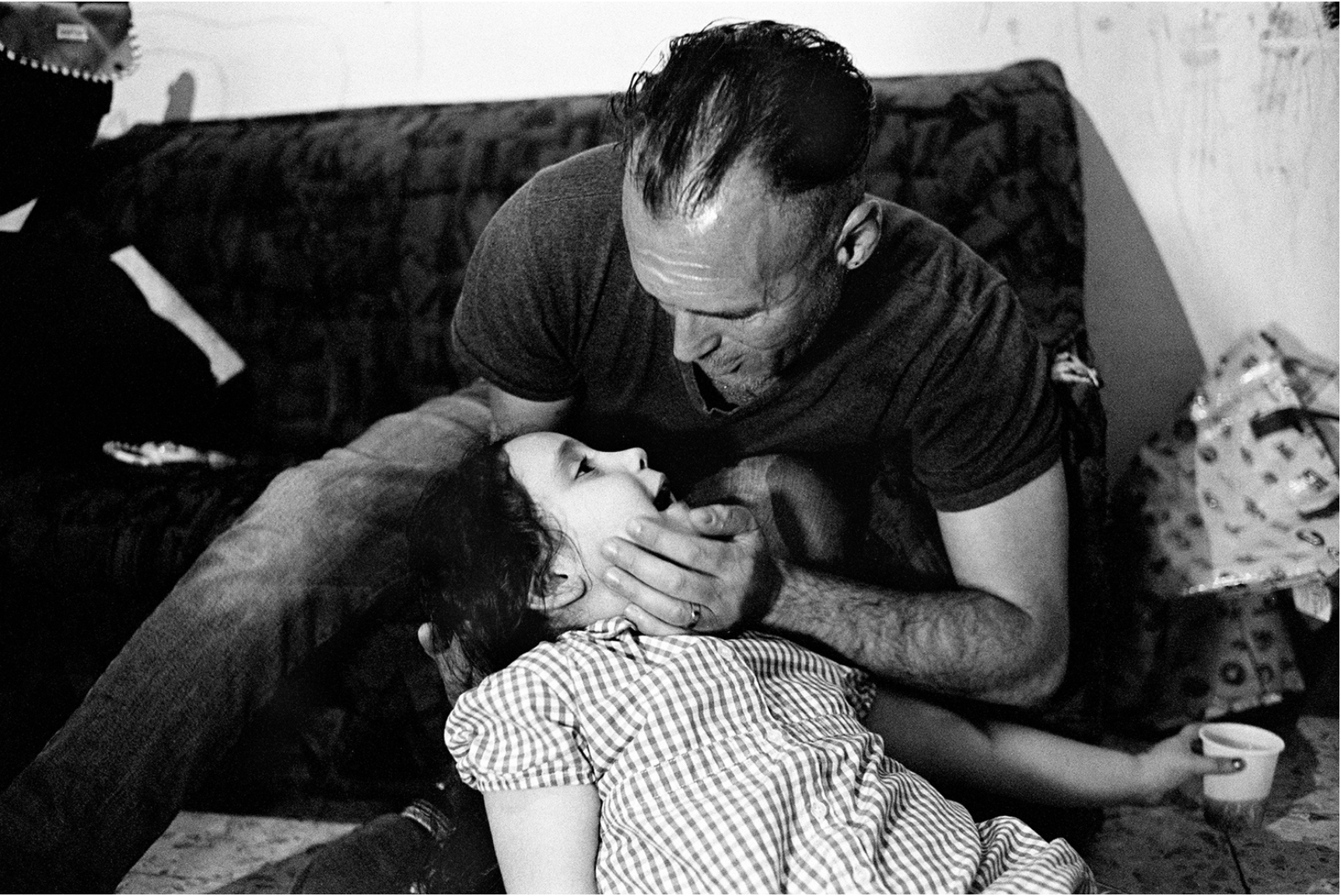

Firstly, I am not interested in the description of the context of these places. I am rather focused on their existential dimension, revealed via a body language that gives a sense to the monotonous flow of lives. The faces and the gestures preserve an enormous and universal power in such a context. But I also want to stress the sensation of claustrophobia that is very present in these houses.

In fact, you entered their very intimate everyday life. What did you learn by spending time with them?

I learned the pleasure of simple things in life. The first questions they ask me when I go to meet them, are “did you eat?” and “how are your darling?” This is a kindness hard to find these days, and it tells me that there are enormous resources of human happiness that are not exploited by contemporary society. At the same time, to paraphrase the late sociologist and philosopher Zygmunt Bauman, we unlearn other “primary” abilities. As he noted, to recognize moral pain is very important. Because it is a symptom, it helps us to recognize the fragility of human bonds.

In your projects there is a strong load of love and beauty, in terms of relationship with the subjects and aesthetics. At the same time though, the work also seems to include a subtle complaint towards the superficiality of contemporary society and the absence of political interest. Do you feel you have a responsibility, via photography, in regards to these concerns?

Unfortunately, there’s no way to change their living conditions with my projects. The economic system and consumerism has a devastating effect on the political environment, continuously creating enormous inequalities while at the same time making an end to our social diversity. I feel the burden to tell about the dignity as I found it in these communities – the uniqueness of these people. I can only hope that my efforts to show what live is like in these places will trigger a certain kind of awareness in our society.