GUP TEAM

Welcome to LTP

Softcover, packed in a metal net / 96 pages / 120 x 160mm

€17

A Labour Treatment Profilactorium, or LTP as it is also known, is one of the last institutions remaining from the former Soviet Union: a sort of forced rehab or prison for alcoholics, where men are isolated from society and obligated to work, for their own medial and social rehabilitation. These places have been mostly abolished in former Soviet countries, due to the fact that the ‘inmates’ have not actually committed any crime, but a few still remain in Belarus. Irina Popova(1986, Russia) was the first photographer to be allowed access into one of these mysterious centres, documenting the process from beginning to end in the book Welcome to LTP, where the residents can be incarcerated for up to two years, without the right to appeal, just for being known to be an alcoholic or drug addict. Their homes are rented out in order to pay for their stay at the LTP and their children are put into care. Popova takes the reader down the corridors and into the bleak rooms of the centre, littered with Soviet propaganda, giving them a taste of ‘punitive psychotherapy’.

The first experience the reader has with the book may be a painful one. A wire cage surrounds the publication, meaning one has to break into it in order to access the book, but the pointed ends of the metal enclosure are sharp and Popova gives warning that it may cause injury. The cage format serves as metaphor to Popova’s message that the prison these inmates are in themselves, having officially done nothing wrong, they are stuck in limbo, unable to escape. Once access is gained to the book, loose paper inserts in the form of news articles about the institution and official LTP documents inform the reader of a few of the multitude of rules, including the fact that residents aren’t allowed to move around without being accompanied by a guard. Other inserts include postcards from a fictional ‘inmate’, Bedya, whose letters to four different women reflect the truth of these institutions: that many people who live there rely on the stability of board and food available there, seeing it as a better option than surviving in the real world. He never actually reveals what he does in the LTP, instead adding a surreal element with musings from his past. The reader does not know if his stories of Paris and Moscow are really his memories or the delusions of an addict in withdrawal.

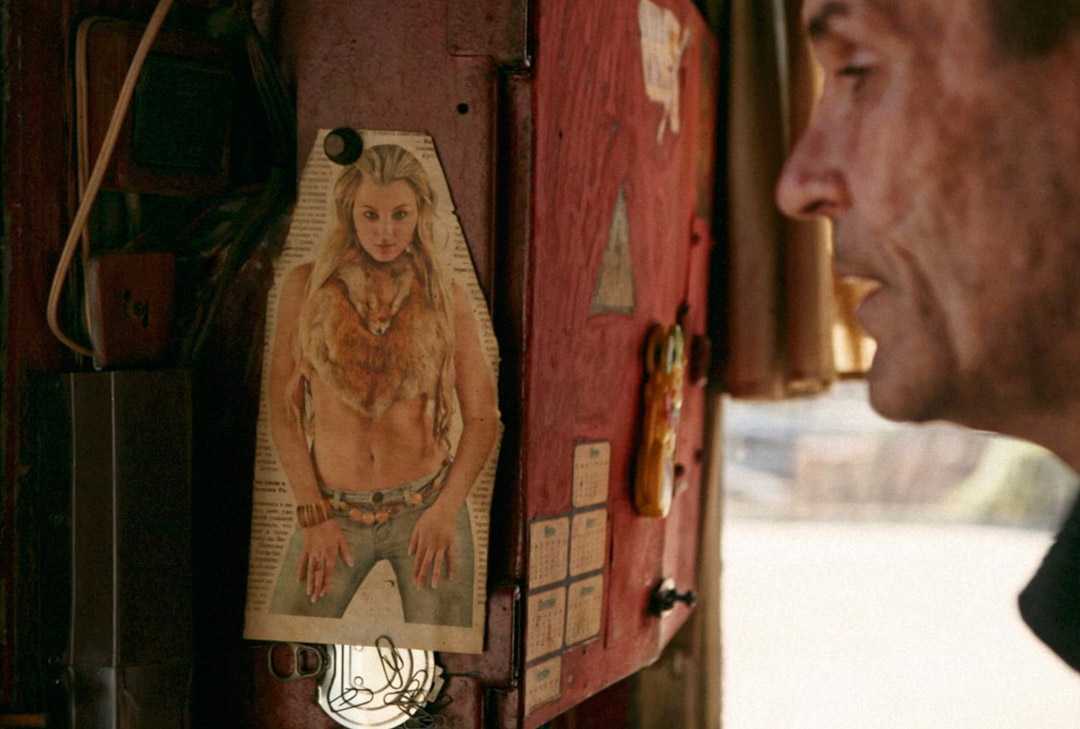

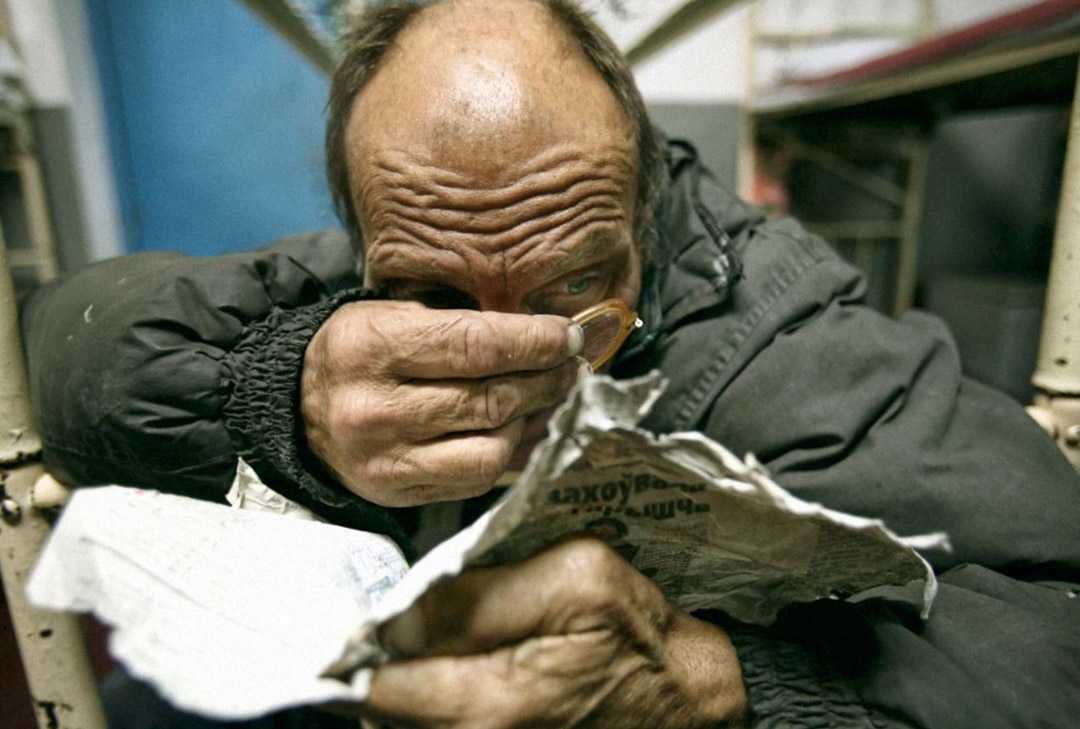

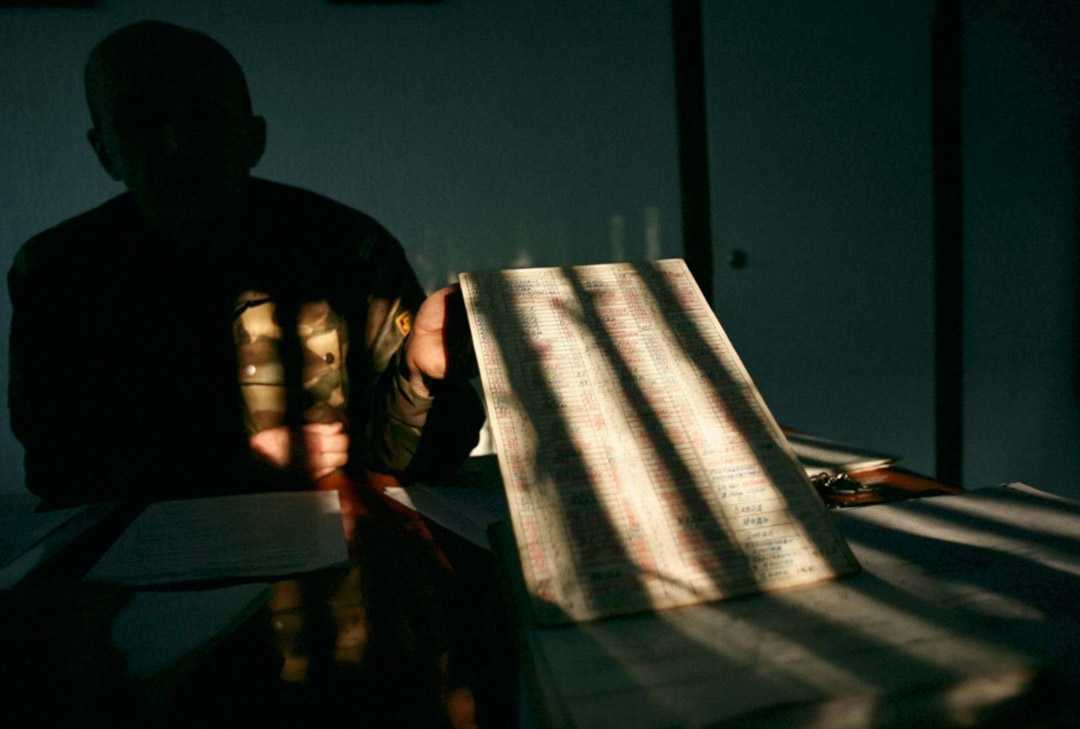

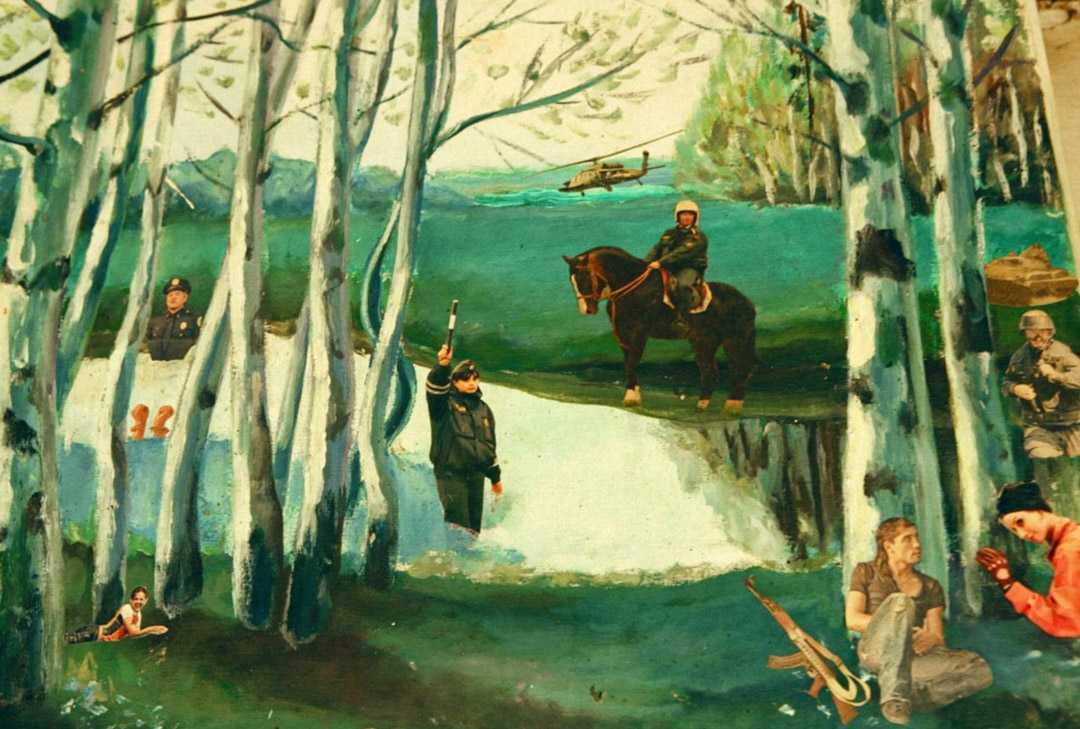

The images themselves convey the bleak, helpless nature of the LTPs: men are shrouded in shadow, often alone, portraying their alienation from society. The residents are captured going about their day-to-day activities, working, eating and socialising, all the while their facial expressions barely changing from resolute solemnity. Soviet propaganda is also painted all over the walls, displaying perfect scenes of what the men are missing and further emphasising the backwardness of such an institution. Welcome to LTP guides the reader through the entire experience, from orientation, to the work duties each resident is required to perform, their individual dormitories and finally, being pushed back into the real world again.

Welcome to LTP is a straight-forward, clear representation of poverty, addiction and loneliness in these Belarussian institutions. The melancholy publication is tinged with surreal elements, from Bedya’s tales, his mind wandering to anything but the place in which he is situated, to the disbelief that places like this can still exist in a supposedly democratic country. The aim of the book is to immerse the reader in the experience of being an inmate, but one feels more like an observer, detached from the reality these men are faced with. It is difficult to connect with the real residents, as the content we see are Popova’s fabrications; their opinions are never heard, the viewer only sees their blank, emotionless faces. Popova is clearly an outsider, something which the reader will also gladly remain.