“The first twenty prisoners arrived at Guantánamo Bay from Afghanistan on January 11, 2002,” writes American photographer Debi Cornwall, in her new photobook Welcome to Camp America. It’s good to be reminded of this fact – that there is a point of time in recent history in which the detention center, within the naval base slangily called Gitmo, did not exist. It’s something that, even 15 years on, is easy to forget.

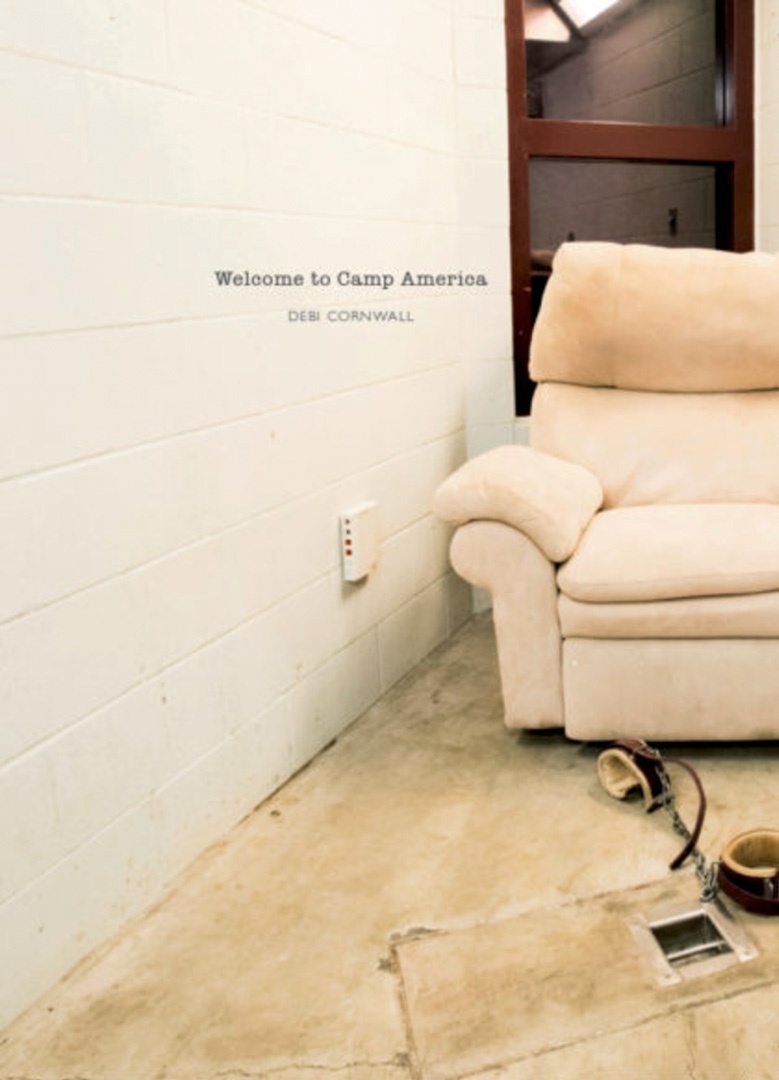

Welcome to Camp America uncovers Gitmo from three interwoven perspectives: the residence and recreational facilities available to U.S. soldiers stationed there, gift shop products, and portraits of former detainees who have been cleared and released. Intermingled with these photographs are documents justifying the use of ‘enhanced interrogation’ techniques (we all know this is torture by now, right?) as well as the transcript of a statement made by a man at Gitmo following a violent beating by soldiers. It’s a lot to take in, and because they’re all mixed together, the effect is one of emotional dysfunction, keeling rapidly between laughter and abuse. It’s sickening. And, because of that, also rather brilliant.

Cornwall, who worked for twelve years as a wrongful conviction lawyer representing innocent exonerees in civil rights suits in the United States, turns her attention to Gitmo in text and images in part because of the location’s unique status as a kind of ‘outer space’ refuge from international law. It’s a matter of semantics. Because the men held there are called ‘detainees’, not prisoners, they are no longer guaranteed the protections of the Geneva Conventions. Gitmo doesn’t have a ‘prison’, it has a ‘detention center’.

She explains: “Of the 780 men who have been held there, only eight have been convicted in the military commissions, and five of those convictions were overturned on appeal. Nine captives have died.” Hundreds who have been held for years at Guantánamo without charge or trial are later cleared and released (and not always to their own countries). It’s difficult to overstate the disruption and damage this can cause. Yet, even the statistics themselves have a numbing effect. Can any of us truly imagine what it is like to be wrongfully imprisoned by a country that prides itself on “liberty and justice for all”?

Cornwall’s portraits of the released men – always shot from behind, to be consistent with the “no faces” rule at Gitmo – are sometimes frustrating for lack of ability to get closer to them, to understand their situation. We learn, in the accompanying captions, some biographical details: his profession, how long he was held at Guantánamo, when and to where he was released, whether charges were ever filed. The cold impersonality is itself like a military file. In this way, the photographer doesn’t hand to you the sympathy you might be expected to feel – you’ve got to do the hard work of being human on your own.