GUP TEAM

The Unseen – An Atlas of Infrared Plates

Hardback / 276 pages / 249 x 27 x 193 mm

€45

Exploring visual realms beyond both photography and the human eye, London-based photographer Edward Thompson (b. 1980) has created the definitive, and perhaps final, photographic book outlining the capabilities and potential of the infrared film Kodak Aerochrome. After it was discontinued in 2009, Thompson sourced fifty-two rolls of the dead-stock film and began twelve mini-projects testing the limits of the format, releasing the results under the all-encompassing title, The Unseen – An Atlas of Infrared Plates.

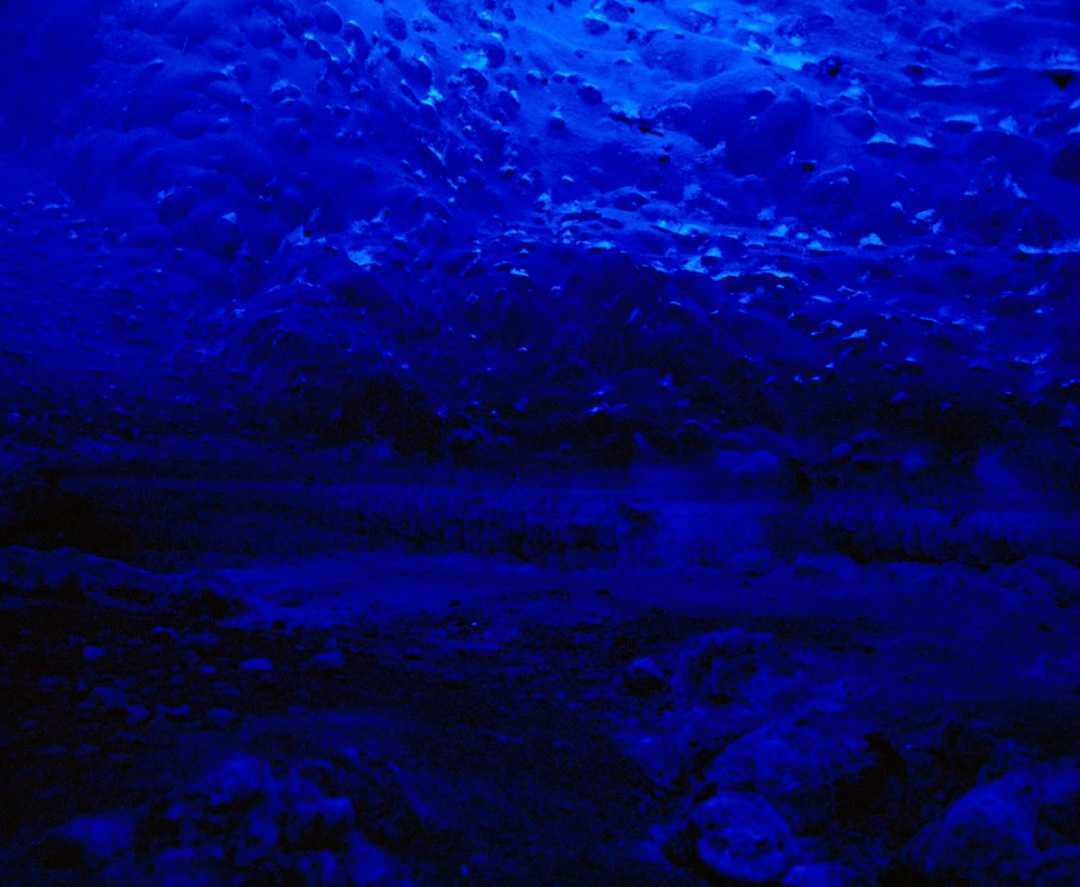

Kodak Aerochrome infrared film – named as such for its sensitivity to light in the infrared spectrum – was invented by government surveillance officials for a wide range of purposes, such as camouflage detection and vegetation surveys. Inspired by the various uses of infrared film throughout history, Thompson decided to use it right across the board, from nude portraiture to natural disaster documentation, and even intergalactic exploration. Seemingly transcending photographic boundaries and genres, The Unseen – An Atlas of Infrared Plates has an authoritative feel about it. Despite being split into twelve sections, there is a coherent, exploratory vision throughout and an inimitable quality about the photography that is totally captivating.

Attempting to ‘photograph the invisible’ – given that infrared film can access almost double the human perception of light – Thompson began in Pluckley, supposedly the most haunted town in the UK, with hope of capturing signs of paranormal activity. Despite being unsuccessful in capturing anything supernatural, the resulting images reveal a bizarrely attractive inferno of red engulfing the quiet English town. Realising the potential of the film, Thompson proceeded to travel the world to document anything the film could see that we couldn’t, such as the extent of the damage caused by Chernobyl to the surrounding area or star formations invisible to the naked eye.

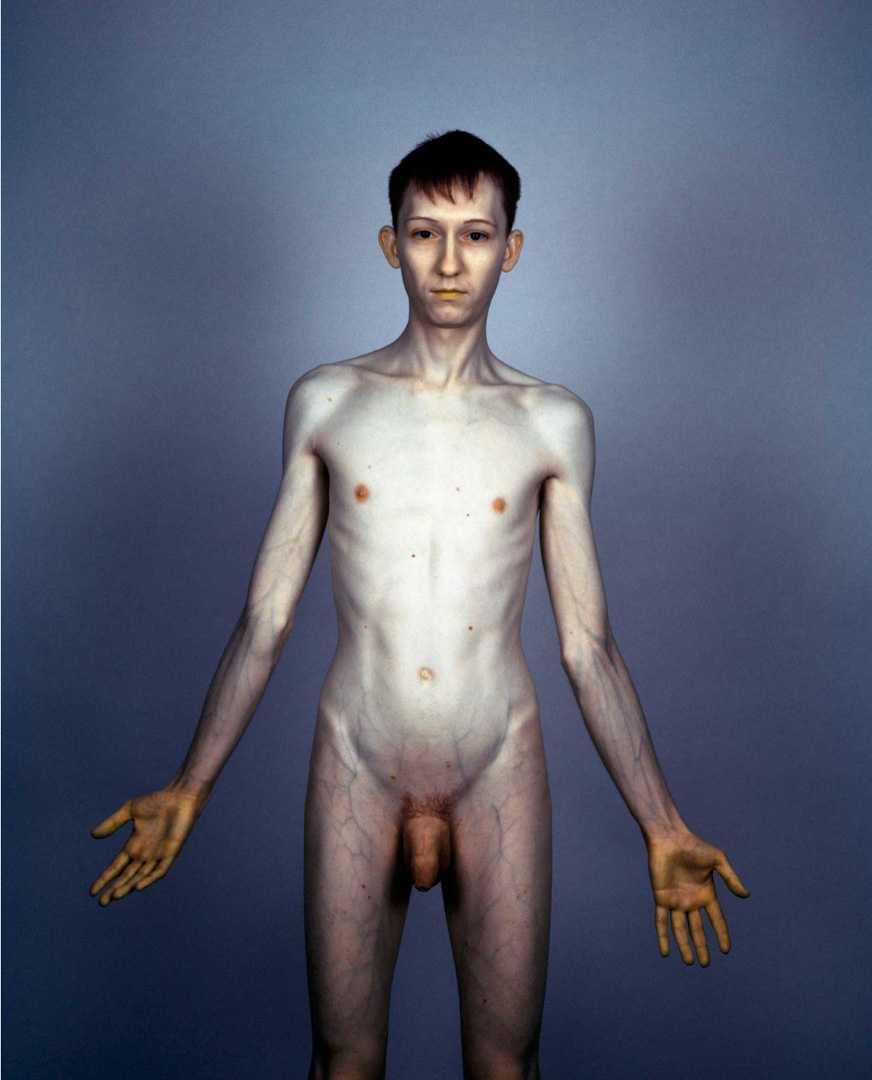

Perhaps the most unusual and shocking experiment would be the eerie ‘In the Vein’ chapter, a section where Thompson photographs a selection of individuals in the nude, posed in de-sexualised, medical stances – presenting their inner arms as well as chests to the camera. The film picks up the veins through the models’ skin and reveals the subject’s “fragile ephemerality” as ghostly dark green tracks visibly run through each subject’s body, which as Thompson says, challenges the conventional understanding of beauty in a nude photograph with all the photo-manipulation available today as the “photographic medium alters our perception of the model, rather than a post-production technique altering the model themselves”.

Creating beautiful images whilst simultaneously raising awareness of serious issues is no mean feat yet Thompson achieves this with ease. However, he stresses that the images were created very much for documentary purposes and the fantastic colours shouldn’t distract you from the message. Regardless, you can’t help but marvel at the beauty of what is probably the legendary Kodak Aerochrome’s swansong.