Sophie Beerens

Paradise City

Hardcover, 206 x 290 mm, 128 pages

€42

In Sebastien Cuvelier’s latest publication, Paradise City, there is a curious photograph of an Iranian city under construction: clusters of identical concrete buildings jutting out of an arid, Mars-red landscape, awaiting inhabitants, yet feeling as if already abandoned. This surreal scene is of the rather ironically named Pardis Town — pardis, from the old Persian paridaida, meaning paradise or walled garden — and it’s a vision of paradise one would be hard pressed to find in the stories of old. If utopia and dystopia were two sides of the same coin, it would, perhaps, look like this.

Cuvelier’s Paradise City is a project born out of discovery — the discovery of a manuscript containing journal entries and photographs belonging to his late uncle, created during a trip to Persepolis, Iran, almost half a century ago. This leads Cuvelier into embarking on a quest of his own, re-tracing his uncle’s steps in an Iran currently far removed from the one depicted within the pages of the manuscript. The Iran of his uncle’s time was one not yet on the brink of the 1979 revolution that would come to irrevocably transform its social, political and religious landscape: one in which 2,500 years of rich, fertile history were being ostentatiously celebrated at the ruins of Persepolis, the former heart of Persia’s Achaemenid Empire. The year was 1971, and it was Iran’s — or rather, Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, the last Shah of Iran’s — way of proclaiming to the world that the Persian idea of paradise was still alive and well.

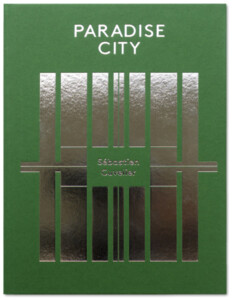

That celebration, both conspicuous in fashion and deliberate in intention, strikes a clear contrast with Cuvelier’s photographs from present-day Iran: the penchant for opulence is long gone, replaced by a sense of nostalgia at times romantic, at others melancholic. The conversation between Iran’s complex past and uncertain future is referenced from cover to cover. As Cuvelier remarks, the idea of ‘paradise’ is inherently Iranian; in fact, the traditional form of the paradisiacal walled garden finds its origins in the Achaemenid Empire, and its four-fold layout (charbagh) is symbolically referenced in the design of the book’s cover. The symmetrical, geometric forms printed on the front side — realized in silver foil against a backdrop of green, one of the three colours of the Iranian flag — seem to convey on one hand a sense of harmony and yet, on another, a more sinister sense of confinement: a parable for the nation under padlock.

“The photographs are often framed in unconventional ways: in one, a view of a sprawling, dusty city is enclosed within a dark wreath of foliage, like an inverted gateway to paradise.”

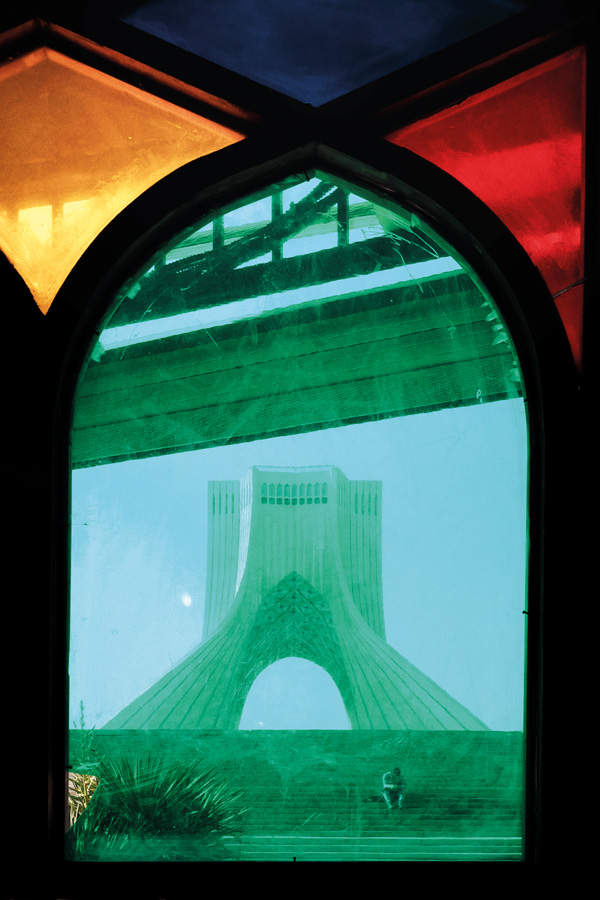

Within the pages of the book, the metaphoric language continues: the photographs are rife with symbolism, and the decisions Cuvelier makes feel calculated, deliberate. Many of the images are superimposed over excerpts from his uncle’s journal entries, often with large portions of text obscured — the journal entries are not simply descriptive in nature, but rather a continuation of the dialogue constantly at play between history and the contemporary. The photographs are often framed in unconventional ways: in one, a view of a sprawling, dusty city is enclosed within a dark wreath of foliage, like an inverted gateway to paradise. In another, an image of a lone man sitting in front of the Azadi Tower is seen through the panes of a stained-glass window. Often, large portions of the photographs are in shadow, allowing only certain elements to come to the fore — Cuvelier conceals as much as he reveals. Flowers are everywhere, although not always in their natural form, appearing in the patterns of scarves, in wall murals, or even in the vivid pink hues of several of the photographs — perhaps an allusion to the ubiquitous damask roses of Persia. They say that early mapmakers would sometimes clean their specialized lenses with rose petals, leaving a rose-coloured stain, and bathing the world in a dreamlike hue. This meticulous framing — in the obscuring of certain details, and the accentuation of others — is revealing in itself: the resulting images set forth an idealized, escapist worldview, and imply a desire to parallel the Iranian government’s alleged perpetration of media censorship.

Within the sometimes stark view of paradise that Cuvelier presents us with, however, is a lingering sense of hope, embodied in the next generation of Iran who hold its future in their hands. “In reaction, contemporary Iranian youth have developed their own notions of paradise,” Cuvelier writes. “For some, it is a small village in northern Iran, where they can escape Tehran’s notorious smog. For others, it is a secluded beach on a small island in the Persian Gulf, away from religious and political constraints. For others still, it is somewhere in Europe or North America — far from Iran — where they can begin a new life.” In the end, perhaps the nostalgia Cuvelier felt so permeated Iran is not one of yearning for the past, but an optimism for a future built upon the rich history that is the backbone of Persian identity. The final image of Paradise City is one of the Volkswagen Kombi Cuvelier’s uncle and two friends bought driving through the arid landscape en route to Persepolis, leaving in its trail a poignant reminder that in order to seek paradise, one must be willing to take the journey.

Sebastien Cuvelier (1975) is a Luxembourg-based photographer. His latest project Paradise City will be exhibited at the Théâtre National Wallonie-Bruxelles from March-April, 2021, and the publication Paradise City is available at Artibooks and Gost Books.