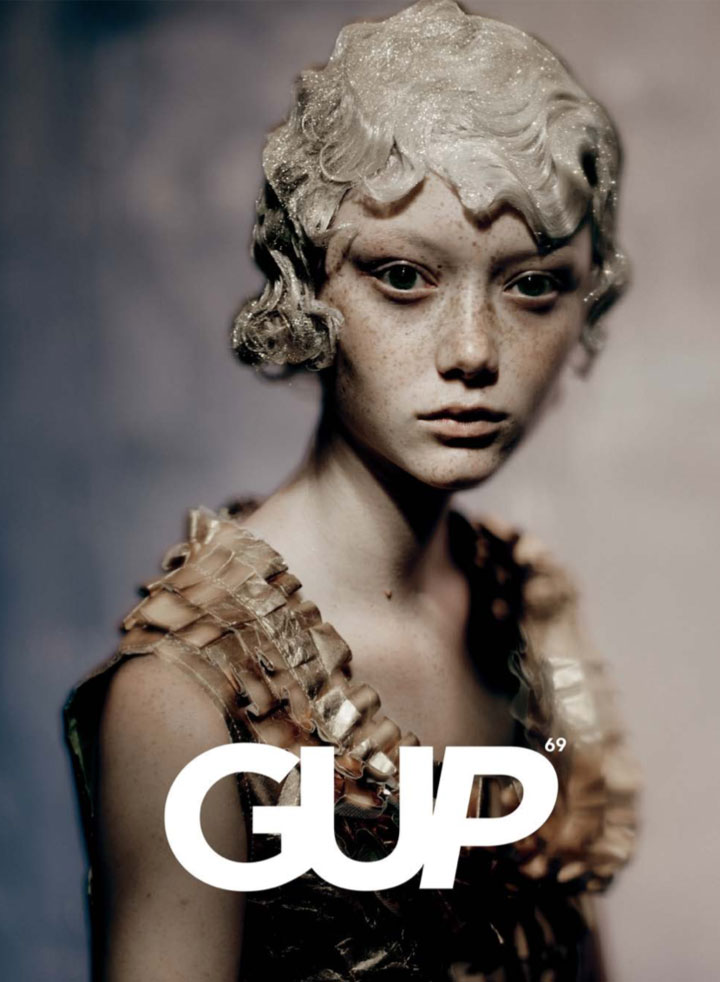

Rayon Vert

CREDITS

GUP Author

Erik Vroons

Artist

Senta SimondTitle

Rayon Vert

Publisher

KominekFormat

Hardcover/ 100 pages / 220 x 225 mm ISBN 9783981982404

Price

€ 45

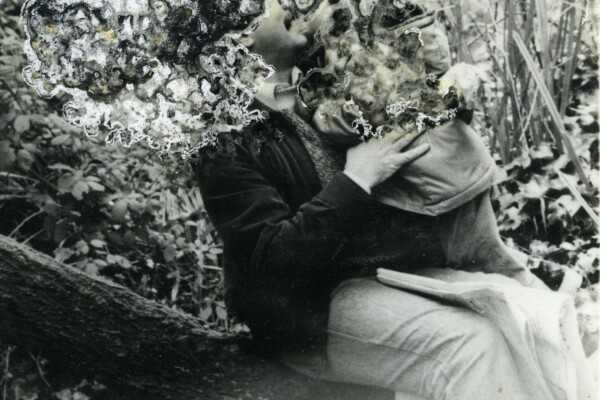

Swiss photographer Senta Simond (b.1989) arranged sessions between herself and her subjects – young female friends she has been closely acquainted with for a decade or so. In these somewhat outlandish photographs, a mix of colour and duotone, the young women come across as empowered, dreamy yet self-aware, and if anything is laid bare – be it a smile, a chest, or a leg – it reflects from the intrinsic performance of their femininity.

Just as in the French New Wave (Nouvelle Vague) films of the 1960s and 70s, Simond’s work breaks with common axes of camera movement. Besides the obvious reference to a film by Eric Rohmer – Le Rayon Vert, 1986 – and the vivid red colour of the clothing being a gesture to the robes of his protagonist (named Delphine), these depictions also contain a head nod to Alexander Rodchenko: the Russian Constructionist who, in the 1930s, was shooting from deviating angles in order to distance himself from existing rules of composition.

Rayon Vert, the book, furthermore includes a range of blank pages; full spreads, sometimes even double spreads, with no image. Although this could be understood as an obstructive gimmick, an alternative interpretation would lead to the conclusion that these ‘non-exposures’ – empty pages following a sequence of one to maximum three pictures and occupying close to thirty percent of the total volume of this publication – actually serves a manner to arrive at a more sequential, cinematographic mode of contemplation.

Eric Rohmer insisted on a more organic social dynamics between himself, the actors and the technicians on set. In fact, many of the French New Wave films were often shot in a friend’s apartment or yard, using the director’s friends as the cast and crew. In line with that approach, Simond too opted for stretched moments of interaction with her companions, colliding with reality while aesthetically opting for visual poetry over photographic documentation.

What we get to see is a culmination of fragments, activated sensations and moods – ranging from spontaneous and frisky to more studious and pensive – arriving from actual gatherings; acutely observed (and then captured) slices of confidential interactions between the photographer and her friends, as they together operated in an intimate space that refuses the pleasure of being occupied by the viewer. The oddly disjointed perspectives challenge the usual transitivity, and the self-contained mannerism in these performances is further undoing the hackneyed way of how young women are commonly being objectified to the camera.

Simond’s Rayon Vert – hinting at the split second of an illuminating splash of green light that occurs just when the sun either appears or disappears behind the horizon, i.e. the scarce moment of an aesthetic revelation – overall serves as an exquisite reverie, highlighting the anomalies of attraction among same-sex comrades. As a final gesture to the cinematic experience, the last pages of the book function as a score, addressing the young women who participated: Axiadé, Anaïs, Barbara, Jenna, Julie, Laurence, Mandine, Marie, Miji, Sunna, Roxanne, Tamara, Soumeya, Zélie. The onlooker might be galvanized by what has been exposed, to the camera, but the time of the actual experience between these female friends remains exclusively theirs.

Senta Simond will be featured in an article by Erik Vroons in GUP #58 – coming in August 2018.