GUP TEAM

Arktikugol

Hardback / 160 pages / 200 x 250 mm

€40

There have been three Russian mines built in the arctic archipelago of Svalbard since 1935, but only one remains open. Barentsburg, the last functioning mine, generates just enough coal to support the local community’s energy needs, and, like all the mines before it, operates at a financial loss. If that strikes you as inexplicable, it’s because you’re thinking of investments as essentially motivated by profit. Yet, located 1100 km from the North Pole and 1100 km from the United States border, Svalbard has served as a strategic Russian observation point since the second world war.

In other words, it’s all about location, location, location.

Arktikugol, the latest book from French photographer Léo Delafontaine, has been released with perfect timing to coincide with renewed interest in Russia’s strategic global position. The author explains Svalbard’s historical significance:

“In 1920, the Spitsbergen Treaty recognized the sovereignty of Norway over the arctic archipelago of Svalbard under the following conditions: that it remain entirely demilitarized, exempt from taxation, environmentally intact, and open to business development from the citizens of all signatory countries. Russia, which ratified the treaty in 1935, is currently the only foreign country to make use of this right through coal mining.”

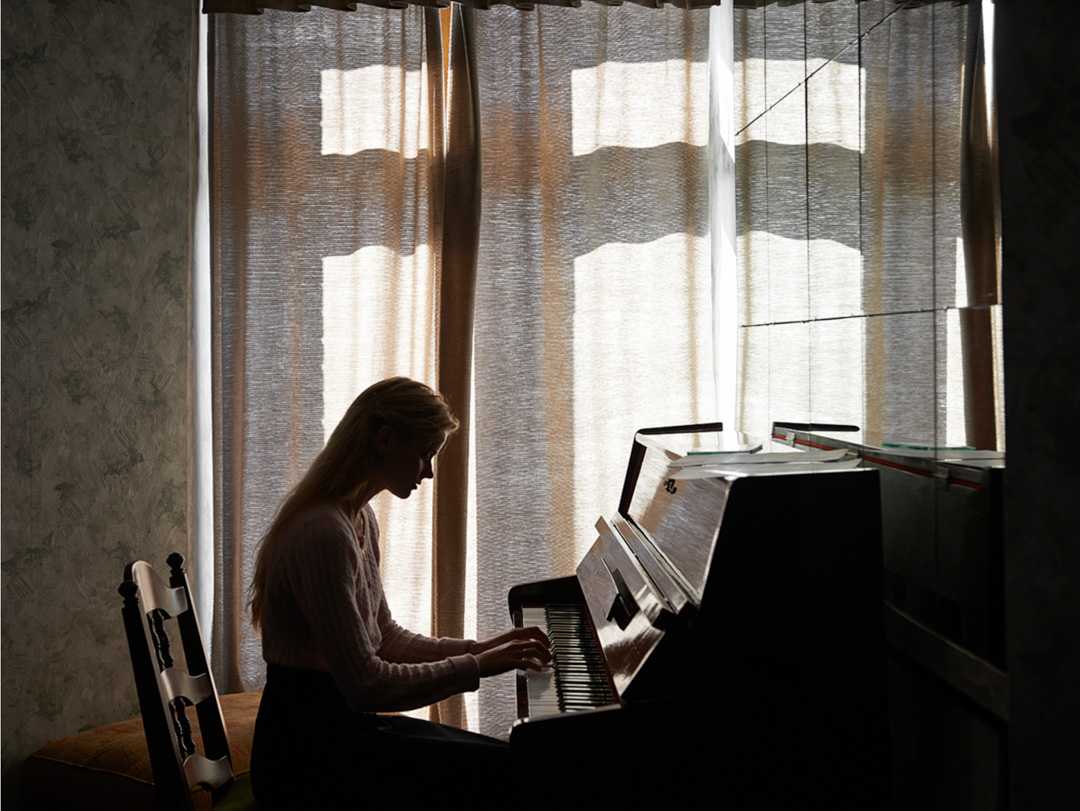

Delafontaine visited Svalbard between Summer 2013 and Spring 2015 to document the area’s inhabitants, exposing the daily lives of miners and villagers. Since early days, miners, mostly from Ukraine, were attracted to the communist utopia of a high pay, tax-free lifestyle — a life far better than was achievable in Ukraine. Due to the coveted nature of these positions, miners were selected for additional skills that could enrich the community, including theatre and musicianship. As such, in addition to the portraits of miners, we see pictures of residents practicing their appreciation of culture through performance, dance or playing the piano.

Arktikugol (literally, ‘Arctic coal’ in Russian) is the state-owned trust that oversees the mine, though Delafontaine explains that it has begun to turn its focus to tourism. Over recent years, a brewery, restaurant, youth hostel and a center for expeditions have opened. These efforts emphasize the state’s awareness of Svalbard’s geopolitical importance.

The environmental portraits in Arktikugol reflect the prosaic nature of life in a remote community. Delafontaine’s photographs are illuminated by available light, whether sunlight or incandescent lamps in a subterranean setting. The effect is intimate but lonely, comfortable but alienated. In the dark mines, the intensity of the light emitted from helmet lamps punch through the shimmery coal grey and crimsons of the underground workplace, awakening the feeling of solitude in darkness and the importance of illumination to provide guidance and the perception — if only an illusion — of safety.

The landscapes, interior scenes and portraits of Arktikugol illustrate the lingering evidence of the bygone Soviet days. The architecture remains frozen in time from the collapse of the Soviet empire. Delafontaine informs us that since the early 2000s, approximately 90% of its population has abandoned the Svalbard archipelago to return to the mainland, leaving a scant 150 in the community. A photograph of a miner passing a decaying rainbow mural questions whether dreams of the rainbow and a brighter future will survive or whether the settlement continues its slow decay into the desolate landscape, remaining merely a pawn holding down territory on a geopolitical chessboard.

Arktikugol has been published by Editions 77 in an edition of 700 copies, in French/English.