Sophie Beerens

Remnants of an Exodus

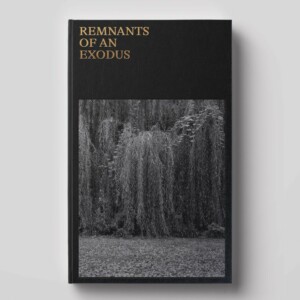

Case Bound, 104 pages, 55 Black & White Photographs

42€

Al J Thompson’s Remnants of an Exodus is a project that could never have arisen from the photographer-as-tourist, or the photographer-as-investigative journalist — that much can be felt within the powerful emotion that resonates in his images. The affection and earnest intimacy, evidenced for the people and places of his former home, can only necessarily emerge from someone who finds his roots within the black and caribbean community being portrayed. With tenderness, in a series of black and white photos, Al J Thompson portrays these remnants of an exodus that has never ended – of a community that calls Spring Valley their home, a place to live, to occupy, but without the privilege of true ownership.

At the age of sixteen, along with his family, Thompson departed from Jamaica and moved to Spring Valley, New York. The year was 1996, and the Spring Valley Memorial Park — which provides the main setting of these photographs — was, as Thompson remembers, “the vibrant heart of Spring Valley’s thriving Caribbean community”. The park was a space that had attained symbolic value: a place of fraternity for the settled, and the still settling; a public space where, in a dynamic and ever-changing world, children and adults alike of diverse languages and accents could anchor themselves.

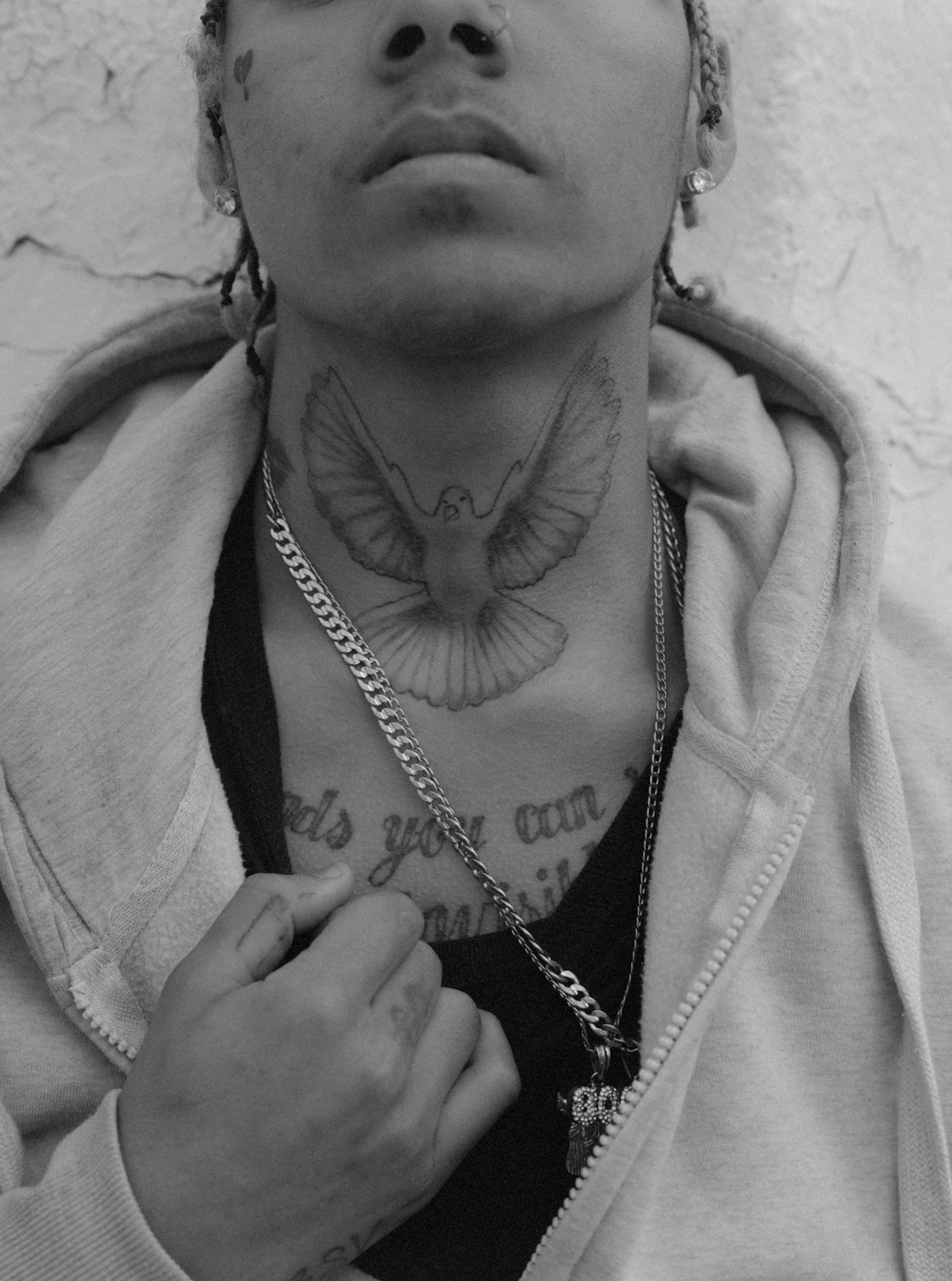

Two decades later, the sound of sneakers on concrete and the laughter of children is subdued — as the black and caribbean communities have been in steady decline. Those that still remain are the central figures of Thompson’s project.

The weeping willow that graces the book’s cover, with its long, pendulous tresses trailing down, appears so thickly layered as to be impenetrable, and rings with the sort of melancholy that is felt in the images that proceed. It’s also an instance of the sort of open-ended, poetic symbolism that appears throughout the book: the willow is a symbol with varying connotations across various cultures, appearing, for example, in Scripture.

According to Christian lore, it was the branches of a willow tree that Jesus clung to as he fell, weary from the cross upon his back, on his way to Golgotha. It’s the first of several allusions to Christianity — with a certain austerity, perhaps, or a command for reverence. In another photograph, a spray painted cross almost glows against the metal bars of the chain-link fence which it adorns. These, too, are remnants of a history that stretches back to the colonization of the Americas, executed by those faithful subjects under the banner of the Lord.

The residents of Spring Valley are then revealed to us in fragments, each photograph measured and contemplative. His subjects are often seen in symbiosis with the nature of their surroundings, sometimes even entangled in it, as if clinging to its reassuring quality. The spectre of gentrification, whose form grows steadily more solid, has expelled many from the neighborhoods they call home, and has caused other neighborhoods to fall into disrepair. Tensions run increasingly high between the black community and the growing population of Haredi Jews, further complicating the social landscape of Spring Valley.

Thompson’s photographs are testimony of the ever-transforming, ever-adapting community of Spring Valley. The energy vibrating from these photographs is never frenzied, and never aimed to come across as being theatrical. All subjects feel at rest, suspended in some undefinable way – yet, this quality of calm camouflages the instances in which the implications may be far more sinister: in one of the pictures we see a pair of legs, in ripped jeans and basketball shoes, ominously or innocently dangling high up in the air. The foliage of a tree can be seen behind the legs, but the photograph cuts off so as to conceal the presence, or absence, of any support. It is an implication that contains too much history to ignore.

At the same time, in the face of this loss, and considering the horrific history echoing from the land and societal upheaval that feels inexorable, Thompson’s images offer a form of respite. There are those who will argue for the inevitability of this dispossession — after all, the land upon which Spring Valley rests was once that of the Lenape people, and perhaps others before them — and for the supposed “benefits” of gentrification. Such an argument, however, neglects to consider the historically disproportionate distribution of such benefits.

The term ‘gentrification’ itself already presupposes a certain inclination towards those who engender displacement — derived from ‘gentry’, the designation of the “well-born, the well-bred and genteel” social class. If this so-called urban revitalization has limited capacity, then is it not simply the modern manifestation of the Biblical exodus to which Thompson alludes?

Gathering Remnants, the essay by Shane Rocheleau that concludes the journey of Remnants of an Exodus, begins with the words of the formidable writer, poet, activist and feminist Audre Lorde:

“Unless one lives and loves in the trenches, it is difficult to remember that the war against dehumanization is ceaseless.”

Lorde, who was born in New York City in 1934 to Caribbean immigrants, recalled that, as a child who struggled with communication, she would often think in poetry, and speak in poetry. It is fitting, then, that the only words Thompson provides us from his own hand and heart, are in the form of the poem that features in the introduction of his publication. As much as his photographs are rooted in the idea of a profound love for his community, so too are the words he gifts us.

To quote Lorde once again: “I am defined as other in every group I’m part of. The outsider, both strength and weakness. Yet without community there is certainly no liberation, no future, only the most vulnerable and temporary armistice between me and my oppression.” Without community, splintered and chipped by centuries of built-up adversity — a community once defined as but three-fifths of a person, no more than the property of those land-owning men who could not even grant them their legal humanness — the fight against oppression has no flame.

Rocheleau’s acknowledgement of the likes of activists Audre Lorde and James Baldwin reminds us that their fight for civil rights began long before and is not yet won. The remnants are unifying, and rising up, asserting, reasserting, their wholeness. Thompson’s project is but one testament to their enduring strength.

Al J Thompson (1980) is a Jamaican-born photographer currently based in New York. His work operates on the intersection of Psychology and Visual Arts, and he continues to investigate the nuances of political and societal turmoil through the photographic form. His latest publication, Remnants of an Exodus, was published by Gnomic Books, and is available here.