The 25th edition of PHotoESPAÑA.(PHE), held between June 1 and August 28, can be covered in two ways: as an all-you-can-see buffet (visiting as many venues as you can possibly schedule) or rather by way of making a strategic selection from its extensive programme. For this anniversary edition, PHE has scheduled 120 exhibitions by 442 photographers/visual artists, concentrated in Madrid but also presented in several other locations in Spain – and abroad. So, good luck to those who lean towards the first option. Even when having an insatiable pair of eyes, assuming that you’re not a local resident and, if in Madrid, only have limited time to explore the festival, it’s advised to opt for a somewhat selective approach.

Herewith shared is a shortlist of recommended exhibitions. Before highlighting some of the exhibitions, though, a bit of context: PHotoESPAÑA launched in 1998 with the intention of giving photography a relevant place in public institutions, as well as allowing wider exposure to galleries specialising in photography. PHE has strong backing from various Spanish cultural foundations and these collaborations often go hand in hand with showcasing career overviews of major local and international artists, exhibited in extensive (and often impressive) institutional spaces, while also giving way to emerging artists – highlighting the work of young creators who are contributing new ways of looking.

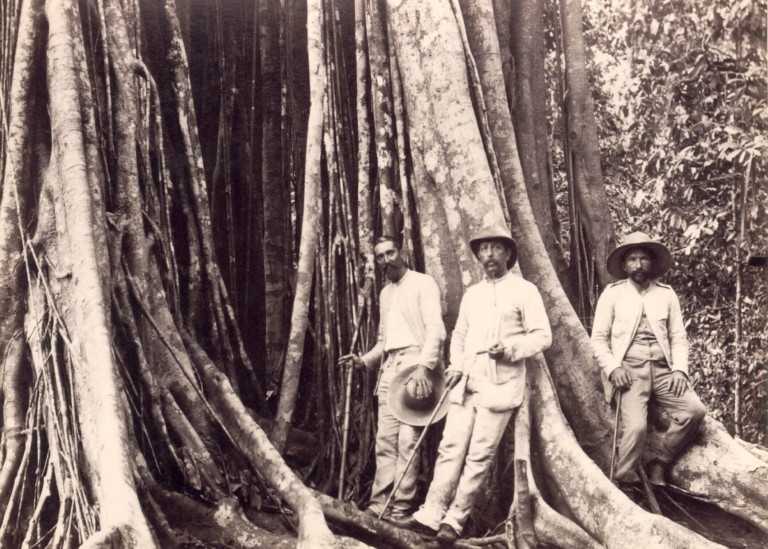

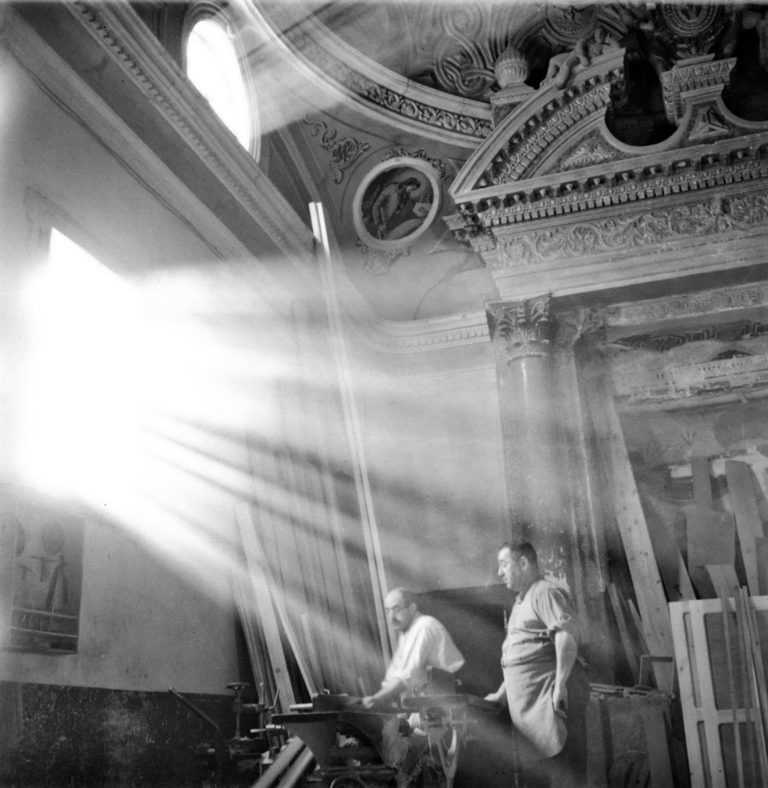

In earlier years, the festival appointed a general commissioner in charge of programming for three consecutive years but it seems that the PHE directors have decided to deviate from that model, appointing a different curator every next edition since 2017. For the occasion of its 25th anniversary, PHE invited Vicente Todoli and Sandra Guimarães as guest curators – presenting ‘Sculpting Reality’, an overview of documentary-style photography as selected from the Fundació Per Amor a l’Art, a private art collection from Grupo Ubesol, based in Valencia. The group show is so extensive that it’s been divided over two venues: Círculo de Bellas Artes and Casa de América. At ‘Circulo’, the curators present an extensive yet somewhat random survey of the documentary style – works of Robert Frank, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Lewis Baltz, Luigi Ghirri can be seen there but it also includes more contemporary (mainly late 20th century produced) works by artists such as David Goldblatt and Joel Meyerowitz. Indeed, predominantly male photographers, be it that there is one room specifically designed for the audio-visuals of Susan Meiselas’ pinnacle work on ‘carnival strippers’ that she produced between 1972 and 1975.

The other section of ‘Sculpting Reality’ is conveniently nearby, located in the Casa De America – just 5 minutes walking from ‘Circulo’. Most of the works in Casa de America are, indeed, made in (Northern) America. But so were several works presented in ‘Circulo’. It’s not made clear what criteria were behind the sections. Presumably, it was mainly a matter of logistics and thus of wall space. The collection simply is too extensive to fit either vicinity and so the curators had to improvise – or so I’m guessing. ‘Sculpting Reality’ is a comprehensive portfolio of documentary style photos, collected on private initiative. Altogether, as noted in the festival catalogue, it reflects on “the narrative capacity of the documentary and its relationship with truth, the interpretation of the scene, and the photograph’s potential as a document to embody political stances in its aspiration to immortalise the social, political and cultural realities of the places it portrays.” Unfortunately, the curators decided to let the pictures do all the work, not explaining the many motives that photographers had in their documentary intent. Clearly, some works are more controlled and serve a subjective comment (e.g. Lewis Baltz) while others are driven by a more political (e.g Goldblatt, Frank) or aesthetic observation (e.g. Meyerowitz or Cartier-Bresson).

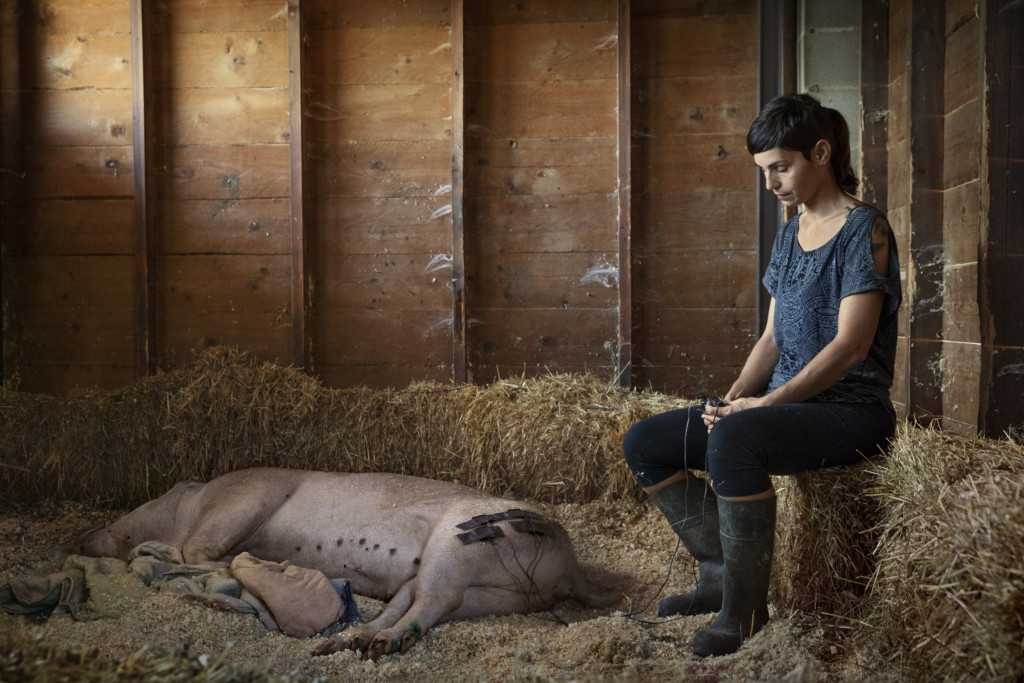

If you wonder what the ‘photograph’s potential as a document’ in the context of socio-political realities is about in more recent times, or even how it will be visualised in the near future, it is suggested to take the pedestrian crossing and visit ‘Hybrids’, the group show curated by Marina Paulenka, at CENTROCENTRO. Initiated by FUTURES – a conglomerate of European photography platforms annually putting forward emerging visual artists – ‘Hybrids’ presents a variety of attempts to foster, in an immersive and exploring manner, a new visual literacy. Crystallising alternative ways of seeing everyday realities, the works of the selected artists mostly arrive from a personal perspective on current issues – mixed with an appetite for experimentation. In the same vicinity, one floor down, you can revisit the ‘Sixties’- how this era has been iconified in printed matter: books, magazines and record sleeves. Divided into themed chapters, ‘Fotografia publica: the Sixties’ offers a kaleidoscopic and vibrant image of that peculiar era in modern print history. That is, the Sixties are considered a golden age of (mass) media culture; a bottomless reservoir of printed photos, on a planetary scale. As becomes clear from this grant overview, photography was omnipresent – globalised – in the 1960s, and the appeal of the groundbreaking books and magazines of those days (first edition copies of the publications are exhibited in glass vitrines and selections of spreads of those books are wallpapered) makes one realise that the times have radically altered for the print media industry ever since.

On walking distance from CENTROCENTRO, the next hub could be Fundación MAPFRE (a non-profit institution created by the eponymous Spanish multinational insurance company), offering a major overview of the Almeriá-born photographer Carlos Pérez Siquier, who was considered an ‘outsider’ by the fact that he consciously decided to live in the periphery of the Spanish art scene of his era. Yet, at the same time, he’d become the catalyst for the AFAL Group (1956-63), bringing about radical departures from photographic conventions of the time. This retrospective, featuring 170 photographs and structured through seven series that are presented chronologically, encompasses a significant number of previously unseen images of Siquier, who was already known in Spain during his lifetime but failed to gain wide international recognition (Martin Parr once accused the maker of being a ‘copycat’ only to find out that Sequier was actually doing vibrant close-ups at the beach long before). Paolo Gasparini, the other artist on display at Fundación MAPFRE, was born in Italy but then emigrated to Caracas (Venezuela) at the age of twenty, and he is embraced by the Latin Americans as one of their own. Significantly, Gasparini was a man of movement and presents his oeuvre not so much in chronological order but rather as a journey. His philosophy as an artist is one of ‘hindsight’; of revisiting themes, places and dates in order to come to a new discourse. Moreover, Gasparini is not shying away from a subjective approach, portraying events from a firm leftist perspective on Latin America, where bold capitalism coexists with stark poverty and where socialist ideals are commonly expressing the many struggles as experienced in daily life – and as witnessed by Gasparini.

If you are interested in the more iconic elements of photography as it developed and eventually found wider recognition in Spain over the course of the twentieth century then you can certainly indulge yourself. Further including: the National Photography Award winner Alberto Garcia-Alix, reappropriating pinnacle art works from the PRADO Museum (e.g. Goya, El Greco, Velásquez) by way of analogue film and double exposure; Javier Campano’s poetic street photography as produced between 1975 and 1987; and the Catalan photographer Francesc Català-Roca, considered one of the founding fathers of ‘concerned photography’.Yes, many of those are male and Spanish but as also stressed by Claude Bussac, the director of PHE (racing tirelessly from one venue opening to the next in order to introduce the curators and artists), the gender gap in photographic history is to overcome by showing work of already internationally acknowledged artists such as Tina Modetti and Germaine Krull – the latter being seen within a modest exhibition, at the Museo Nacional del Romanticismo /The National Museum of Romanticism. The main focus is on a set of private snapshots which nevertheless signify a pinnacle historical moment: that of forced exile ignited by fascism.

Fascism, forever marked in the Spanish collective memory due to the longitudinal force of dictator Franco and his allies, is also touched on in a persistent study of a long-lost archive that was recently (re)discovered in Amsterdam, home to the Institute for International Social History (IISH). Over the course of seven years, researcher Almudena Rubio worked at this institute to disclose the photographic endeavours of two brave young ‘extranjeras’: Margaret Michaelis (Poland, 1902-1985) and Kati Horna (Hungary, 1912-2000), young foreigners who came to Spain in the 1930s, motivated to document the anarchist movements (against fascism, mainly). These archives were long considered to have been lost but now, thanks to the endless energy and perseverance of Rubio, we are allowed a better understanding of this very difficult and yet very important period in Spanish history.

Also worth visiting within the framework of PHE 22:

The ICO Museum (ICO is a corporate state-owned entity) presents an overview of commissioned and autonomously produced work by the Spanish artist Juan Baraja (b. 1984). Baraja often revisits locations to document the gradual changes of the architectural landscapes, commonly environments that tend to lean towards oblivion. He also applies his large format camera to highlight the functioning of architectonic elements in natural environments that are nevertheless defined by man; Casa Árabe, serving as a meeting point between Spain and the Arab world, hosts an exhibition that includes the works of twelve photographers originating from Lebanon, an artistic collective that also includes the curators of this group show. Collectif 1200 was formed in 2019, at the time when Lebanon was in socio-economic turmoil and the artists felt the need to co-support each others’ art practice, fundamentally documenting their personal perspectives on the precarious situation that their country was in and still is, all the more so after the devastating explosion in Beirut (August 4, 2020). Through their various practices – documentary, conceptual, performative, mixing still and moving images, etcetera – the collective presents an amalgamation of experiences; of perpetual struggles and resistances, while also giving expression of hope and love. In short, of everyday life in Lebanon.

In 1998, introducing the first edition of Photo Espaňa, photography occupied a very discreet place in Spanish art. Today, so many festival cycles later, photography has seen an exponential rise in recognition and attention, both by institutions and from the general audience. Perhaps the directors and curators of this 25th anniversary edition could have put more focus on the photographic movements of today. They could also have offered firmer guidance, bridging between eras and movements – as actually is done in the Palacio Real de Madrid/ the Royal Palace of Madrid, where selections of Sebastião Salgado are seen side by side with archival images arriving from the Royal Collections of Patromonio Nacional. Overall, it can be concluded that PHotoESPAÑA. is not meant to exclusively serve a ‘niche’ audience of ‘photographistas’ and that the festival direction is rather committed to further expanding the goals as set for themselves in its earliest days: broadening the interest in photography in Spain – and giving wider exposure to the local artists of the past and of the present in close collaboration with all sorts of foundations and institutions. This is what they do very well and the city of Madrid has the perfect cultural infrastructure to host the many PHE-exhibitions on offer this summer.

For more information, visit: