Between the 1960s and ’80s, the expansion of cheaper air travel sparked the holiday package boom to European “sun, sea and sangria” destinations such as Benidorm and Torremolinos. It was also a golden age of travel that began to place the delights of luxury hotspots on the French Riviera and Italy’s Amalfi Coast – previously the preserve of the rich and famous – within reach.

These destinations were made to appear even more glamorous through advertising images in travel magazines and pictures on postcards. But how authentic are such locations, really?

To enhance the visibility of Europe as a tourist destination and increase the number of international visitors, the European Commission recently started to undertake a wide range of communication and promotion activities regarding travelling to and within Europe. But what is Europe? Is it merely a geographically demarcated area or does it also apply to a communal ideal?

For many people, the question has an obvious answer: it is a continent, a specific part of the Earth’s surface. One can stand on its soil. However, it is not merely a natural fact of geography. That is, it does not possess essential and unchanging characteristics. “Europe” is, in its essence, also very much a concept fashioned by humans, established and reinvented according to historically specific belief systems and ideological principles.

What can we make of it? Who shall we be on arrival? For a long time, travel magazines were the perfect medium in which to transcend the mundane notion of Europe and turn it into a fantasy. But the holiday destinations depicted in these glossy brochures are not real. Not unlike the postcards one can send to loved ones at home, they are the projection of an ideal, a “package” for the tourists to unfold and then mould into a subjective, projected, idealised shape.

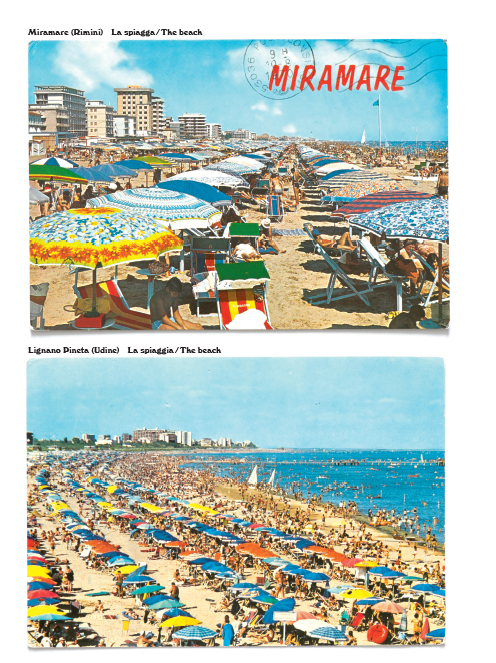

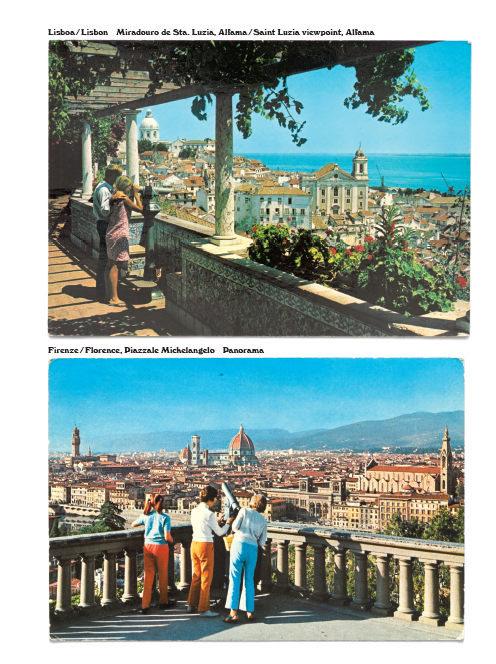

Since their inception in the late 19th century, the main purpose of a postcard has been to act as a souvenir for tourists, a reminder of the places and sights visited on “once in a lifetime” holidays. According to Beat Schlatter (b. 1961), one of Switzerland’s best-known cabaret artists and an avid collector of postcards, they bear similarities with good pop songs in the sense that they are massively reproduced items that can still contain a distinctive personal touch.

How authentic are the subjective reports written on the back of postcards?

Schlatter’s comment contributes to the notion that a place can be shared by many while not necessarily delivering the exact same experience for everybody. The cards in his collection date from the 1960s to the 1980s, the apogee of European tourism. These postcards – very personal and nostalgic reminders of carefree past times – depict beautiful scenery, idealised landscapes to be explored. But these preset vistas, as defined by the picture-postcard industry, have limited scope.

How authentic are the subjective reports written on the back of postcards? The images on the front, for a start, are extremely biased. “Amongs the more than 3,000 postcards that passed through my hands while preparing this book there is not a single one in which it is raining,” Schlatter writes in the opening essay of Postcards (2020). He arranged 400 postcards from his collection into 12 pictorial chapters, including beach promenades, cityscapes by night, alpine roads, snow-covered winter scenes and so on.

The travel industry planted the seed of wanderlust, encouraging the masses to explore the continent. They helped to promote bucket-list destinations in Europe, while brochures and magazines helped to attract a growing audience to the concept of leisure travel.

The main purpose of these “glossies”, not unlike postcards, was to feed a mass promise or a commonly shared desire. Which brings me to another recent and interesting photographic project.

For New Meridians, Eva Stenram (b. 1976, Sweden) assembled images from issues of the German travel magazine Merian published between the mid-1950s and early ’60s. These photos are the record of landscapes and towns as they were at the time of the Treaty of Rome, which established the European Economic Community in 1957. Stenram overlays the original images with her own markings: vectors, lines and tangents suggesting new alignments and structures.

Grids and demarcations are erased and redrawn, new meridians are created. The cartographic annotations added by Stenram could mean many things: lines of communication, movements of people or goods, borders, landscape usage, as well as the introduction of systems and laws – but also fractures, fault lines, rifts. Yet they are abstract enough to refrain from imposing a fixed key or cipher.

With this manner of appropriation and creative interference, Stenram aims to address how the ties in Europe, which held for so long, are once again uncertain. She suggests that the European Union is undergoing a severe mutation that affects its markets, household issues, health systems, food chains and environment.

Grids and demarcations are erased and redrawn, new meridians are created.

The emergence of ethnonationalism within the boundaries of Europe is another matter, meanwhile and, ironically enough, one that finds an overlap in the ideals as depicted in the travel brochures and postcards of yesteryear: the fairy-tale version of a tribal continent, idealised by images that function as traces of Europe’s mythical heritage.

Schlatter’s postcards of post-war European destinations hint at the commercialisation of a diverse cultural and natural common treasure, while Stenram’s annotated travel-brochure pages indicate a more political motive, to depict Europe as a stable continent with unique historical assets that are to be explored and personally experienced from up close by the many. Either way, the idealised version of this ‘Europe’ has never existed in the real world and it will remain an allegory.

Eva Stenram (b. 1976, Sweden) originates from Stockholm, but currently mainly works in Berlin and London. Her photographic practice brings together archival material – negatives, slides, magazines – images from the Internet and photographic prints, and these are subsequently changed through digital, analogue or physical manipulation. By muting and mutating her material, the original functions of the photographs are disrupted and often subverted.

Beat Schlatter (b., 1961) lives in Zürich and is one of Switzerland’s best-known cabaret artists, actors and script-writers. He is also a keen postcard-writer himself, and over a period of thirty years, has gathered an extensive collection.

This article was published on GUP #65 – EURO.