“Every new beginning comes from other beginning’s end,” noted Seneca – the Roman Stoic philosopher, statesman, dramatist. In AD 65 he was forced to commit suicide, a punishment for an alleged involvement in a (failed) coup of emperor Nero. But that’s beside the point here. What matters more, for now, for the sake of my argument, are Seneca’s rather wise words on the paradoxical meaning of ‘beginning’ and ‘end’, and I’d like to elaborate on this in the context of two photographers who I recently encountered, during the opening weekend of a photography festival organized in Landskrona, Sweden.

Leif Sandberg (b. 1943, Sweden) was in his early sixties when he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. “Receiving a death sentence is special, to say the least. You think you know everything, have been through it all, and feel you can be practical about it. But it pierces your soul like a sharp dagger,” he writes in the opening page of his book, Ending (Boecker Books, 2017). Life was no longer in the hands of Leif. He embarked on a journey with no clear destination. A fearful one, also for his beloved wife.

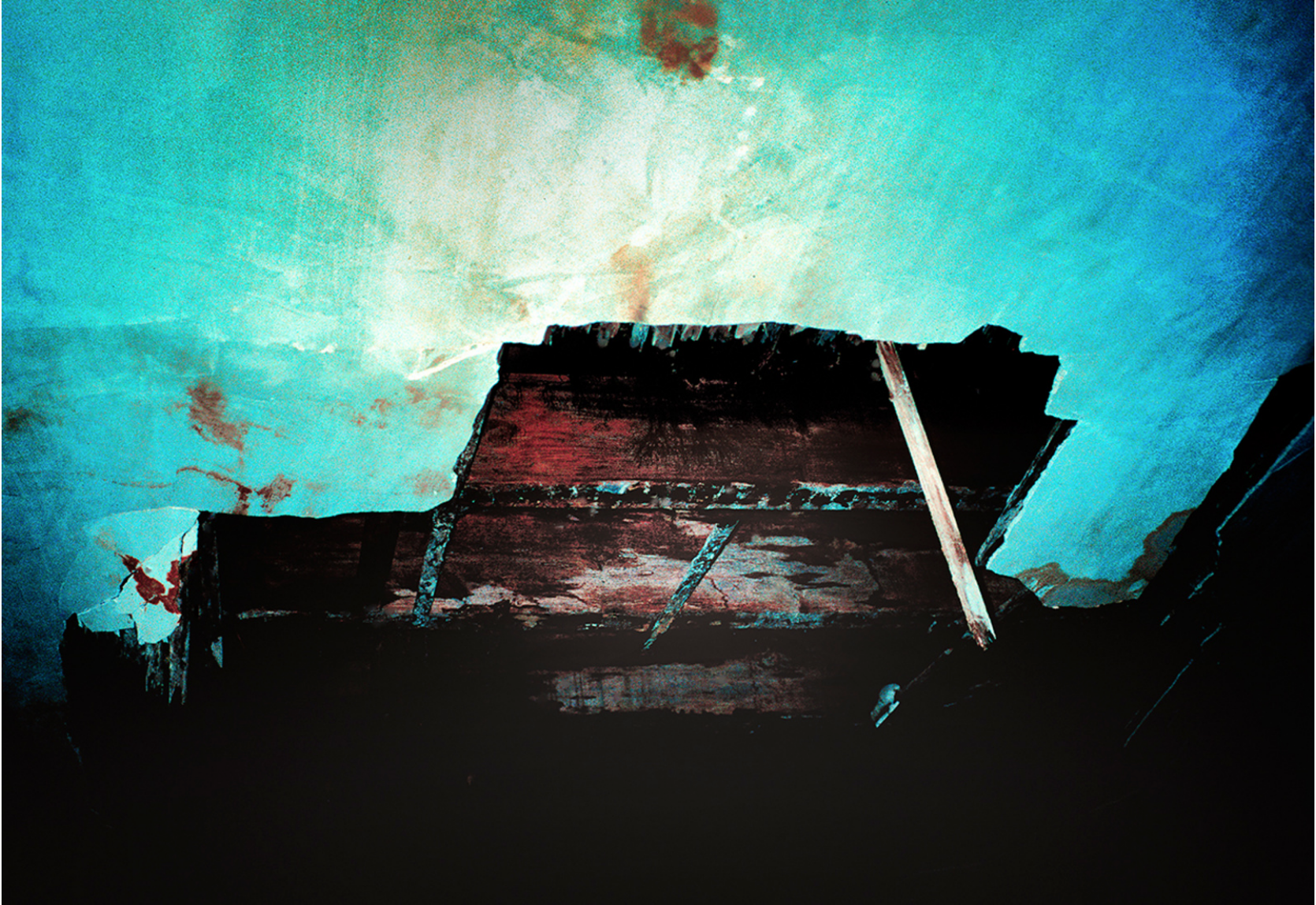

The book is the visual result of Leif’s emotional endeavor, a metaphorical reportage of the all too real emotions that were felt while living in a state of despair. Photography can indeed be a useful tool to give expression to the unbearable and incomprehensible doom. Picking up the camera in times when life seems utterly meaningless is a reflex that is not uncommon, nor is it a rare thing to apply photography as an expressive translation for a certain state of being. For Leif the activity of photographing was of utmost necessity, as the need for preservation is considered all the more urgent once the Grim Reaper has been announced.

What Leif documented, first and foremost, was fear itself. The terror, the alarming panic, the agitation, the dread, dismay, distress, the anxiety, the worries, and the nerve wracking angst; the fright for the new beginning that already announced a soon (and defining?) ending. For what was to come afterwards? More than dealing with this insecurity – for who knows what’s next – Leif’s existential self-portraits (and the objects that serve as allegorical hints of his nightmarish situation) are made in the full awareness of an absolute end-stage, which heightens the urge to document existence as it is.

“Every new beginning comes from other beginning’s end,” noted Seneca.

Kacper Kowalski (b. 1977, Poland) was not diagnosed with a similar kind of malady. In fact, he is surrounded by a seemingly endless life, full of possibilities. Yet he failed to connect with it at some point. More exactly, after 20 years of flying – first as a paraglider, later as a pilot of small aircrafts and a gyrocoptor – Kacper felt that his job of producing stunning photographs from a bird’s eye perspective was more or less over. A done deal, not only because of the arrival of unmanned aerial vehicles (i.e. drones) but perhaps even more so due to a subjective ‘crisis’, to be summarized as an internal conflict with his obsession for flying.

His book Over (self-published, 2017) is a collection of snowy Polish landscapes as seen from above, made in the familiar style which defined Kowalski’s artistic signature over the course of his career as an aerial photographer: all images are abstract (due to the deviating perspective) and all landscapes initially look untouched but are actually disrupted.

While gliding over the surface of the earth, approximately 150 meter above ground level, Kowalski was capable of depicting graphic yet often abstract landscapes that are seemingly pristine but always include a hint of civilization. Where does nature end, exactly, and where does human adaptation begin? His images, even though monumental in scope, do not give an easy answer to that question. They rather confront the onlooker with the fragility of our existence. Along the way, however, Kowalski’s connection to the world he was recording faded. This addiction to escape was never really a problem, until it was.

He for long felt that he was on the right track, but fear came to bring doubt. “Darkness enveloped me, I was in exile from my own kingdom, an outcast from a neglected past, adrift and with no hope for a happy ending.”

At some point, both in their own way, Sandberg and Kowalski got to understand the value of their camera in relation to Seneca’s profound wisdom: every new beginning comes from other beginning’s end. Whereas one of them was pretty sure he needed to photographically document his ending in order to continue to feel alive, the other was very much in doubt about the continuation of a vacuum. Although the situations are incomparable, Kowalski thus entered a ‘zone’ to which Leif arrived after he received his ‘verdict’. Or, in the words of the poet Bob Hansson – notes on a photographed death, cancelled – as published on the last pages of Sandberg’s book, Ending:

walking among the ruins

of our own self-image

what other dreams can we hold?

What other is there than the remains of a life lived? This is what has been questioned, photographically.

“Through horizonless [sic] fog I move instinctively from one shape to the next […] I plunge deeper and deeper until all that remains is the here and the now, within which I meditate.” These comforting words arrive from Kowalski’s afterword as included on the last pages of his book, but they could just as well arrive from Sandberg too, as it is the expression of an urge to apply photography in order to find peace with a certain disturbance of life. When the curtain was about to fall, they started the projection. Just in time.